Art Talk with Roger Shimomura

Roger Shimomura is in many ways a study in contrasts. His paintings are visually bright and frequently humorous, even as they expose the dark underbelly of stereotypes and racism. They are unquestionably American, even as they warp idealized visions of American life. And their flat colors, borrowed from pop art and comic books, belie their thematic complexity and depth.

In many ways, these contradictions are manifestations of a recurrent theme throughout Shimomura’s life: having to defend that he is American, even when others insist that he is not. Born in Seattle to American-born parents, Shimomura was interned as a child with his family at Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho following the enactment of Executive Order 9066—legislation signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942 that legalized the incarceration of Japanese Americans. Shimomura has returned time and again to this period through his painting and performance art, drawing from his own recollections, his grandmother’s diaries, family photographs, and research. His explorations of the subject can be found at a number of exhibitions that mark the 75th anniversary of the order’s passage, including Year of Remembrance at Seattle’s Wing Luke Museum, which is participating in this summer’s Blue Star Museums program, and Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and WWII at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Shimomura has continued his probe of race in America beyond the internment, finding regrettably fertile ground within his personal social interactions and the daily news. This body of work has earned him four NEA Fellowships in painting and performance art, and a spot within the collection of over 90 museums. Shimomura, who also taught at the University of Kansas in Lawrence for 35 years, recently spoke with us by phone about the development of his aesthetic, his fascination with stereotypes, and the continued struggle for artists of color.

NEA: In an earlier interview, you said that when you were a child, you drew "everything my family could not afford to buy me, and the latter example is when art became magical to me." I was wondering if art still feels magical for you now?

ROGER SHIMOMURA: I think it does. I don't know if I'd use the word magical. There's something maybe overly poetic about that, and I've probably become much more of a realist since then. But nonetheless, the whole creative activity is one that's sustained my interest for my lifetime.

NEA: A lot of your work deals with very specific instances, whether it's your own memories or your grandmother's memories or maybe encounters with racism. Can you talk about the process of translating these experiences onto canvas or the stage?

SHIMOMURA: That's really striking at the heart of my working process. I can't say that it's formulaic. A lot of it is a touch-and-feel, "I know it when I see it" kind of thing.

One of the problems when you're working with the kind of material that I work with is that it's easy to start being preachy. I've always told my students that what you end up with if you follow those first tendencies is propaganda, not painting. I don't think any artist wants to end up being a propagandist in their work.

So I have found that 90 percent of what I do is to strategize about how you somehow slip these out without being overtly obvious about it. Along the way, maybe you even introduce people to some of the ideas that you're working on, and maybe you can convince them.

But whatever you end up doing on that painting, it's not set in stone. There's no right answer. There's no correct response. Each person brings their own experiences to it and finishes it a little differently. So that's how far off I’m willing to move on an idea in order to communicate something to the viewing audience. Sometimes it gets pretty far removed from the preachiness that I'd started talking about. But I've decided that that's okay. That works for my paintings. It's so doggone hard just to get people to respond to work, much less respond to it in a certain political way that I don't think there's anything wrong with that.

NEA: Is that frustrating as an artist when you feel people maybe totally miss the point?

SHIMOMURA: No, because I ask for it. That’s part of the menu. That's part of the possibility. That should be part of the fun of engaging in work, that you could miss it completely, but maybe two months later when they see the work, something kicks in. Or perhaps maybe something outside of the theme of the exhibition might kick in and you might be having some sort of parallel experience. That’s fine, because it's hard enough to get any kind of a response from work. Someone once said that the average viewing time for a painting is less than ten seconds. Imagine when the artist puts their whole lifetime into doing a painting, so to speak, and someone views it for less than ten seconds.

NEA: You mentioned evoking a response. Obviously, a lot of your work depicts visual stereotypes, which of course can be very provocative. How you think your art can counteract these stereotypes even as it portrays them?

SHIMOMURA: You're talking about a part of what I do that in some ways fascinates me the most. It's taken me in all sort of directions, this idea of stereotypes. I've been quite vocal about a lot of the ugly World War II stereotyping of Japanese people, in particular, that happened in this country, and was perpetuated on things like “Jap hunting licenses” and "Slap-a-Jap" club cards. These were all things that were given away to kids. The result of all the studying that I've done of those various stereotypes has brought me to a conclusion that it's really the Japanese Americans that suffered for that—not the Japanese. The Japanese were not in this country during World War II. They were on the other side. But the American people had to associate these with someone, and they associated them with the innocent Japanese Americans that were already behind barbed wire and being blamed for Pearl Harbor and everything else.

I’m a collector by nature, and ended up acquiring everything I could find off of eBay [that featured stereotypes]. Things like salt and pepper shakers with the typical depiction of Chinese and Japanese [people]. I had over 450 pairs of salt and pepper shakers of Chinese and Japanese people. Then I started collecting Halloween masks that were of the depictions of Asian people, and other kinds of clothing, furniture, everything. I ended up with this huge collection, and I ended up donating it all to the Wing Luke Asian Museum in Seattle into their archive. It makes me feel good that they're getting better use out of it than I ever did.

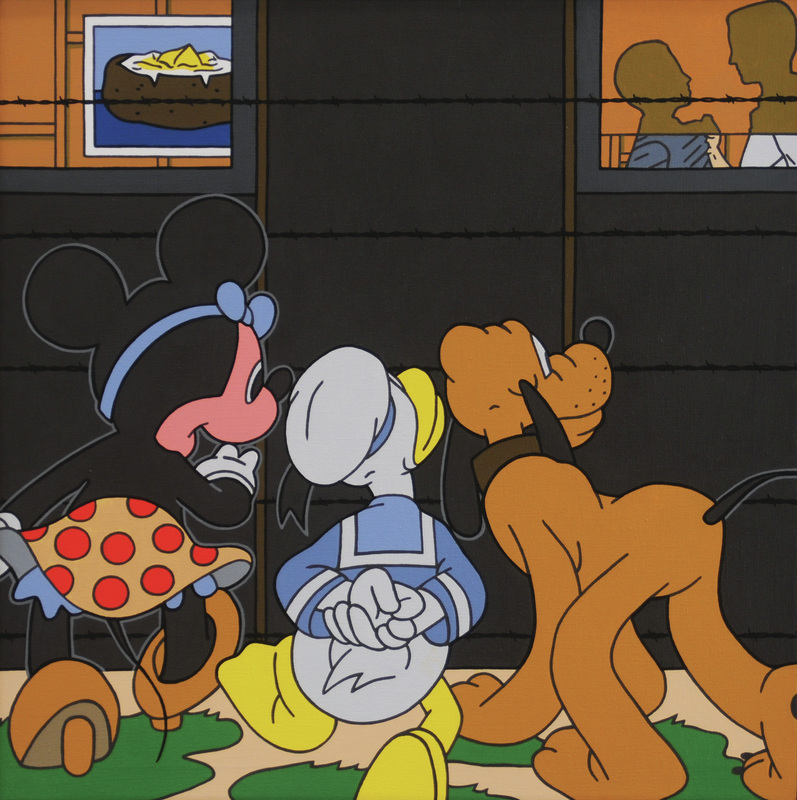

But having those things around infected the imagery of my paintings, and pretty soon, I was painting from all of these horrible images. It did not make my dealers very happy because they're not things that people would purchase and hang on their walls, and understandably so. But nonetheless, they were the kind of paintings that I thought had to be done by somebody. So what I did was I depicted myself as that yellow stereotype, making love to Minnie Mouse, American icons. [I was] trying to cast fresh light on what it was to be called or to be labeled as a stereotype.

NEA: In light of this history of suffering: can you describe what might be the joys and burdens of being known as a Japanese-American artist?

SHIMOMURA: This was something that I struggled with in my earlier years. Why is it that the only time that people of color would get an exhibition is when an exhibition had that title [referring to a minority] or labeled us as such?

The struggle that women have had certainly parallels [the struggle of] people of color. But then the next step breaks it down even further. From the standpoint of Asian America, it appears that African Americans have broken through and are now finally being collected. But I can't name one Asian-American art collector in this country, not one. I'm not talking about the sort of collector that fills up their walls and stops collecting. I'm talking about one that has an appetite that continues and after their walls are filled, they start upgrading their work and even traveling their collection. There's nothing that even approaches that to my knowledge as far as Asian-American art goes.

I just saw in a recent Census that there are 19 million Asian Americans in America—that's less than 6 percent [of the population]. Because of that, the attention that they receive breaks down the same way too. There just isn't any kind of force that they have upon museums to enhance the whole idea of collecting Asian American art. I feel lucky to belong to as many museums as I do. But a lot of those were because I've offered work to them because I felt that it was so important to have work about the incarceration in their collection—something that will stimulate or start some kind of dialogue on that event. Museums have been happy to accept work on that basis. But that's still entry through the back door. It's not like coming in as a collectable artist.

NEA: I read that after your family's time in the internment camps, you said that anything Japanese was more or less scrubbed from your home. I was wondering how you reconnected with that identity and how it then made its way into your art?

SHIMOMURA: I don't know if I reconnected in that sense. My wife and I built this house. If you look at it, there's still virtually nothing Japanese in it. What I have around me are things that I like to look at, and very little of that comes from Japan. Even though I could appreciate all of the things and understand the beauty and the seriousness of a lot of those artifacts, it almost feels like it's of a different culture. I think that really points out, too, the fact that I'm an American and I’m a product of this country. I'm not necessarily proud of the fact that there's so little Japanese in me. However, I have to admit that I seem to have spent my whole life trying to demonstrate that I’m as American as you are. As a result of that, I've lost some of my own identity. I could see how it was sort of rinsed out of my life as I watched my grandparents' generation, my parents' generation, what they suffered and paid for, and then my generation and what I experienced, and then to look at my children, who don't even realize that they have Japanese blood in them.

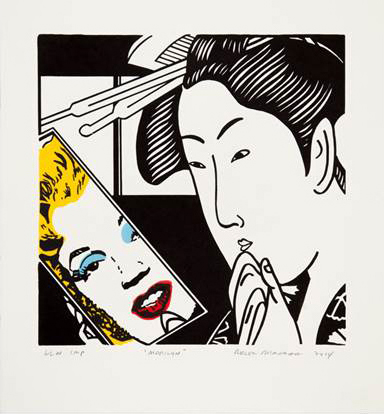

Marilyn (2014) by Roger Shimomura. Lithograph, Edition of 74, 14 x 13 inches. Image courtesy of the Flomenhaft Gallery

NEA: It struck me that you said Japanese objects might not be something that you like to look at, yet Japanese influence is very much present in your work. How did your very distinct aesthetic emerge from this mix of Japanese woodblock, pop art, comics, etc.?

SHIMOMURA: I think the pop came first. [After dropping out of the University of Washington graduate program], I applied for graduate school at Syracuse. The whole East Coast was under the spell of Andy Warhol, and [Roy] Lichtenstein, [James] Rosenquist, [Tom] Wesselmann—all the pop artists. I fell right into that. At that point, I was doing things that could be mistaken for Warhol's work.

But then when I got to Kansas for my first teaching job, all of a sudden, I was in foreign country. All of a sudden, I was Japanese again and people were asking me, "How did you come to speaking the language so well? Where are you from?" All of those clichéd responses that any Asian American would tell you happens to them anyplace off of the West Coast. That's when I did my first painting that looked Japanese. But at the same time, I saw it as another pop painting because the Japanese art that I knew about, or had seen, were all Japanese wood block prints, and those were very pop. It was just a stylistic step sideways really.

I did this painting called Oriental Masterpiece and put it in a show in Seattle along with seven other paintings, all the same size, that were about Buck Rogers' Spaceship and Minnie Mouse and Kentucky Fried Chicken and things like that. It was the one painting that stood out, although stylistically, it was the same—flat, bright colors. I was seeing it as a sort of pop expression—brash, bright, in your face. But someone came up to me at my opening in Seattle where I showed these eight paintings and said, "I really like that painting you call Oriental Masterpiece." I said, "Why do you like it?" They said, "Because you look like that. It's like a homecoming. You're painting what you should be painting and how you should be painting it." That really stuck with me because that's the one painting that subject matter-wise was foreign, and yet people associated that with a coming home party. What I'm getting at is that in some ways, the way I was seeing my own work was maybe a little different than how other people were seeing my work.

NEA: How do you feel your work with performance art and painting overlaps? Or do they satisfy totally different aspects of your creativity?

SHIMOMURA: One of the reasons that I got into a performance is because I had so much raw material to work with that didn't lend itself to paintings. It had directly to do with the amount of things that my grandmother left behind. It all started with her diaries that she started in 1906, which is the year that she immigrated to America, and which she maintained for the next 56 years of her life. They were all written in Japanese, so I couldn't access them easily, but my dad had kept them around and kept telling me, "These are yours one day." I understood how valuable the documents were, but I really didn't know what I supposed to do with them until I came across the idea of trying to get the diaries interpreted and seeing if there were paintings that might be inspired by the entries. That led to the first diary series, and it led to years and years of work.

It turned into performance when I discovered that she left a lot of tapes with her own recordings, her own voice. She had this wonderful sense of history in this country and recorded a lot of her feelings about America. But I think the most important document was just a year or two before she passed away, she and my grandfather both wrote a letter to their relatives in Japan outlining their life in America, and a summary of what it was like to immigrate and come to this country and what she did. My grandmother had led this very colorful life as a midwife, delivering over a thousand babies in the Pacific Northwest—I was the last baby that she had delivered. Before she and my grandfather mailed the letters, they tape-recorded them.

To have all these things—they simply don't translate to paintings easily. You can't hear her voice on the painting. That certainly had a lot to do with the ease of which I moved into performance.

NEA: I’ve read that your favorite subject to teach was actually performance art.

SHIMOMURA: My feeling about performance comes from the fact that I taught painting for so long. It wasn't until about 1985 that I decided that I wanted to try teaching a class in performance. I was writing my first performance piece, and became so engrossed in it and so excited by it. I was facing all of these people, a lot of whom were students at the university, in my performance. It was a refreshing relationship, because the things that we talked about were a little different than the things that had become stale over a period of so many years of teaching. So it was a real shot in the arm for me to all of a sudden switch over. I was learning every day. I was just half a step in front of the students, and frequently, a half step behind the students. But whatever the case, it was a real eye-opener for me. It was the most refreshing thing that I think happened to me during my teaching career.

NEA: It’s clear that whatever medium, you do an incredible amount of research and are also incredibly prolific. Can you describe your actual creative process—research, when or where you paint, etc.?

SHIMOMURA: Now that I'm retired and have been retired for 13 years or so, I'm finally leading the life of an artist and getting up in the morning and painting and painting as long as I want to all day and into the evening and looking forward to getting up the next day and doing the same thing.

NEA: What sort of mark you hope that you have made on the general American canon?

SHIMOMURA: Compared to my white counterpart, I have not made a mark at all—a virtual blip. I know I've shown more than my white counterpart, probably have more catalogs, which I'm hoping will substitute for lack of museum representation. But there's a certain frustration level. I feel like I've done as much as I can, and I’m constantly looking over my shoulder to see whether or not things are getting better for other people like myself, other Japanese Americans. I have, over the years, left behind a small group of artists that are continuing along similar trails, and I think that they're certainly much better organized than I or my counterparts were when we were their age. They're elbowing their way into small museums and getting shows. So I think things are better. Do I feel that they're going to be much better? Frankly, no, not in the foreseeable future. A lot of that just has to do with population. The majority population, we just simply don't care that much when it affects such a small group of people. For most of them, they've never met a Japanese American in their life.

Things here in Lawrence, Kansas, where I live, are different, and I like to think that it's because I've lived amongst them for so long and shown so much in this area and at the local museum, sort of force-fed these issues. So people within a 100-mile radius of Lawrence, Kansas, are probably the most well-educated in terms of Japanese American issues than any other group anywhere, but it's going to take a long time for things to change on a national basis.