The Artistic Autobiography of José Leonilson

Long before the age of chronicling our private lives through tweets, selfies, and Facebook statuses, José Leonilson chronicled and shared his inner world through canvas and thread. His autobiographical artistic practice has given the Brazilian artist, who came of age during the 1980s, a fresh, modern feel nearly 25 years after his death.

“His ruminations of his private life and his intimacy are very much in vogue nowadays,” said Gabriela Rangel, chief curator of the Americas Society in New York. “I think a millennial sees that, and identifies with what Leonilson is saying. He doesn't have any filter. He just says what he thinks and what he feels. That's something very contemporary—that kind of unfiltered account of your life.”

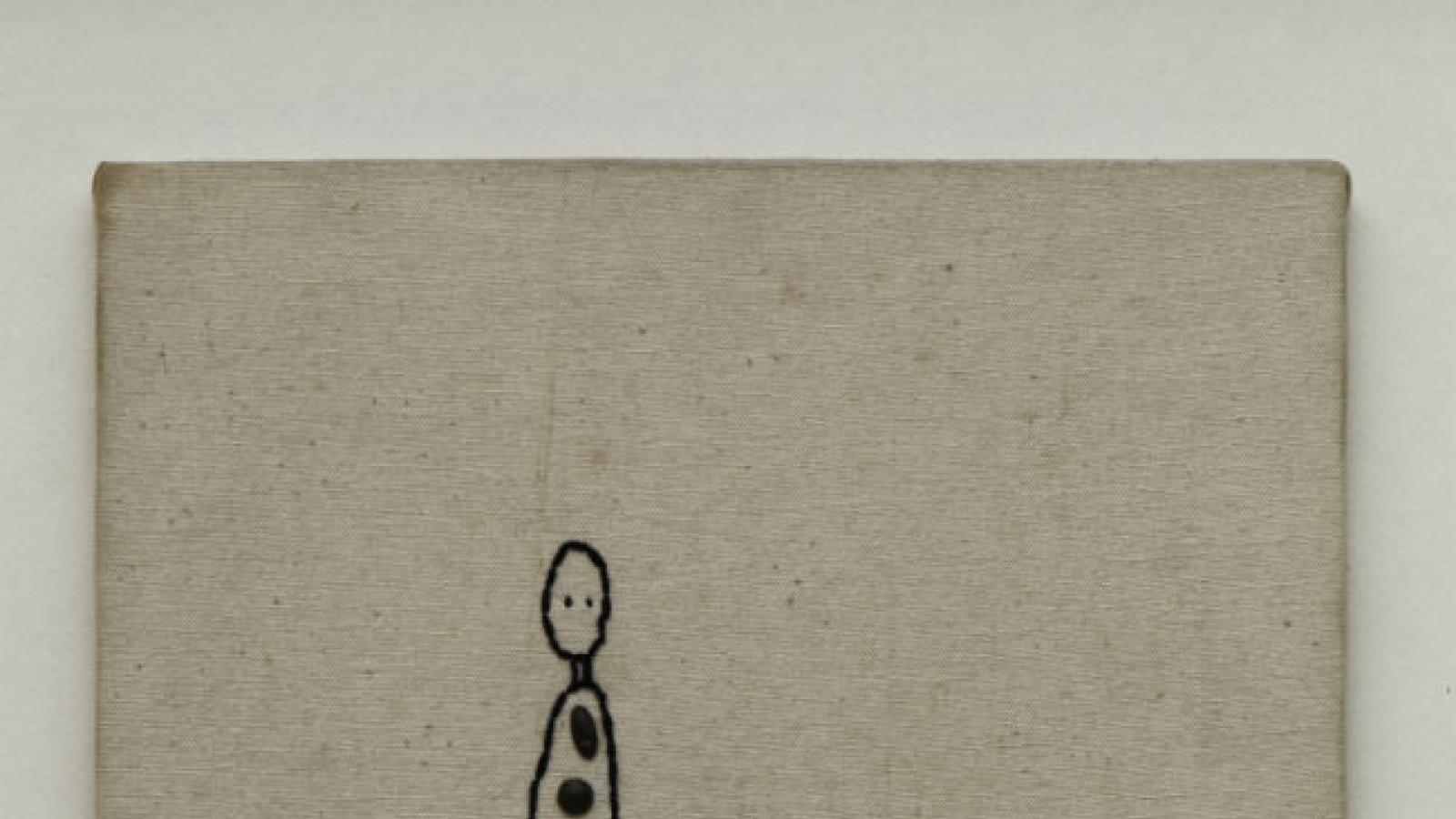

This fresh relevance can be seen throughout the works on display in José Leonilson: Empty Man, on view at the Americas Society through February 3rd. Co-curated by Rangel, Susanna Temkin, and Cecilia Brunson, the show marks Leonilson’s first solo exhibition in the United States, despite having works in the collections of institutions such as New Yorks’ Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Tate Modern in London. Supported by an NEA grant, the exhibition includes drawings, paintings, and embroideries that span from 1975 until Leonilson’s death from AIDS in 1993.

“Leonilson is known primarily, unfortunately, because he is part of this generation that was lost to AIDS,” said Temkin. “But in our selection, we wanted to push beyond such a simple association between the disease, and really explore the complexities of his identity and biography.”

The range of work reveals recurring themes, all of which expose autobiographical elements. His fixation on religious iconography such as crucifixes shows the impact of growing up in a heavily Catholic country; his fascination with language highlights his travels around the world; and his depictions of the human heart and body increase as he grapples with his impending death. Even the act of embroidering itself reveals personal details: a childhood spent in Ceará, one of Brazil’s main textile centers, where his father traded in fabric and his mother embroidered.

Leonilson also frequently subverted traditional gender norms, assigning the incorrect gender to Portuguese words (for example, his piece O Ilha, or “the island,” is given the masculine article “O” instead of the grammatically correct feminine article “A”). Similarly, his adoption of embroidery, which he began to fully explore after his diagnosis, marks the pursuit of a traditionally feminine art form, one whose tender, decorative qualities are unnerved by stitched messages of one-night stands, blood, and coronary arteries.

“He's dislocating these fixed notions of gender,” said Rangel. Temkin agreed, noting that Leonilson’s concept of gender fluidity resonates more strongly today than it might have in the 1980s and 1990s, particularly within the machismo culture of South America.

It was another way that Leonilson probed not only his own world, but also subtly challenged the viewer to reconsider his or her own, much as a close friend might in a private discussion. “When you place yourself in front of the work, you feel that he's talking to you. He's exposing himself—there's intimacy there,” said Rangel. “In a world of monumental and spectacular artworks, [Leonilson’s work] has the intimacy of discourse. It's very subtle. He's not using billboards to convey this. This is very delicate.”