Drawing Ideas with Roz Chast

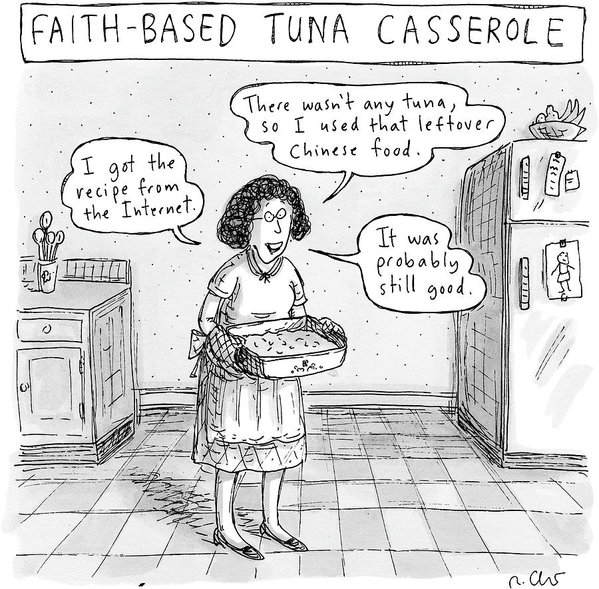

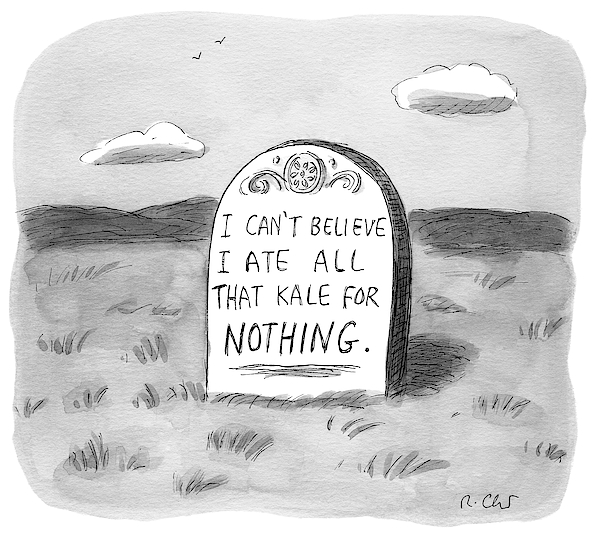

Roz Chast has been making America laugh out loud since 1978 when she began drawing for The New Yorker. In her cartoons, illustrated books, and graphic memoirs (her latest, Going Into Town: A Love Letter to New York, comes out October 3), she deftly chronicles the oddball nature of being alive in a universe overflowing with strange human beings behaving strangely (and also normally, whatever that is). Her work runs the gamut from poking fun at the madcap among us to darkly hilarious renderings of tombstones, weird signage, turns of phrase, widgets, and life at home and on the city streets. You name the thing and Chast has likely skewered it. Again and again, she trains her sharp, self-aware eye on the absurd and the ridiculous, but with that comes an empathy for a topsy-turvy, hysterical, awkward, and (at times) unpleasant world. Her words and images have the ability to reflect back a society that often makes little sense. At the same time, her cartoons document and celebrate people doing ordinary things, which in her hands become extraordinary miniature portraits of the mundane.

In this audio piece, among other things, we learn how she joined The New Yorker’s staff and how her illustrations are infused with a particular kind of anxiety. Additionally, visit the NEA Facebook page to see a few choice cartoons by Chast as she discusses them. You'll get to "Meet Mr. Twitters," "Donna and the Disasterettes," and learn about her very first and very strange New Yorker cartoon, which was controversial in the late 1970s. Oh, and she really, really likes drawing robots.

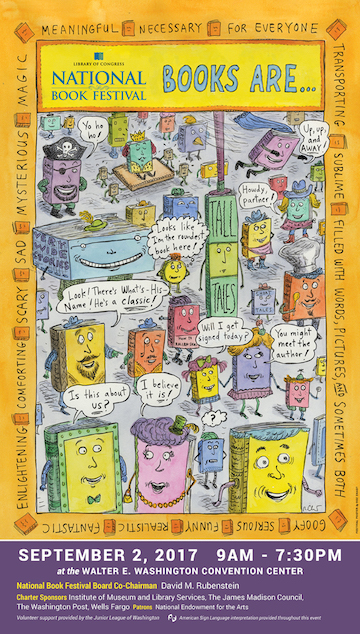

Here are some examples of her doing what she does best and her design of the 2017 Library of Congress National Book Festival poster. The festival is September 2 in Washington, DC at the Convention Center. To learn about the NEA's amazing Poetry and Prose stage, go here.

Roz Chast: Cartoons are this kind of wonderful sort of interaction between the visual and the verbal.

And in fact, the cartoons at The New Yorker, they used to be called idea drawings not cartoons. You have an idea and then you draw it. Adam Kampe: THANK GOD ROZ CHAST HAS BEEN DRAWING HER LAUGH-OUT-LOUD IDEAS FOR DECADES. SHE’S MOST FAMOUS FOR HER CARTOONS IN THE NEW YORKER, BUT SHE’S ALSO AN AWARD-WINNING GRAPHIC MEMOIRIST. CHAST MADE A CAREER OUT OF DRAWING WHAT SHE FINDS FUNNY, STRANGE, OR SAD. SOMETIMES ALL AT ONCE. IN THE PROCESS, SHE’S MADE SCORES OF PEOPLE LAUGH AND FEEL LESS ALONE. HER ORIGINAL BRAND OF COMEDY STEMS FROM ABSURD INVENTIONS AND RAZOR SHARP OBSERVATIONS ABOUT HUMAN BEHAVIOR, MUNDANITY, ANXIETY, AND WHAT HER MOTHER CALLED THE “CONSPIRACY OF THE INANIMATE.”Roz Chast: "Conspiracy of the Inanimate." Oh, it means when everything starts going wrong. You know, where you're tying your shoe and then the shoelace breaks. And then you go into the cabinet to find more shoelaces and then you knock something over and then that's a mess, and so then so you have to clean that up. And then you open up the cabinet but the cabinet door falls off in your hand, which once happened to me. You know, it's just like this endless cycle of things turning against you.

If it seems like a funny thing, I'll jot it down. Usually things are going along really swimmingly. That's not for me like when the funny stuff starts happening. I mean a lot of times the things that are like the worst become kind of funny in retrospect. Most people who are writers and cartoonists that I know tend to analyze things and get kind of bent out of shape about things that other people say, "Eh, forget about that." And it's like, no I can't. You don't understand. I have to unknot this before I go on, you know. And if I don't it's just going to wait a little while and then it's going to be a bigger knot. I knew I wanted to make my living as a cartoonist. I couldn’t imagine any other job. I really couldn’t. But my goal was I thought I would be a cartoonist for The Village Voice, which was a sort of underground-ish but very established publication. And Jules Feiffer did cartoons for it, Mark Allen Stamaty, Stan Mack. There were people whose work I super admired and I felt like I had more in common with them than any other publication that I had seen that used cartoons. And even back then, there weren’t tons of publications that used cartoons. Cartooning as a thing, I think, had passed its golden age. Magazines had, in fact. I was published in The Village Voice I was starting to get a foothold there and I was selling to The National Lampoon also, which was around back then. And then I thought, “Well, I’ll try The New Yorker.” My parents subscribed. I knew they used cartoons. I didn’t see that my stuff had anything in common with the cartoons there but I thought, “Well, why not?” And I was 23 and I got everything I had pretty much together at 60 cartoons and I called up and I found out when their drop off day was. That was what they had back in that day. If you were submitting over the transom, you dropped your stuff off and then you came back the next week to get it. So I dropped it off, came back the next week to get it and there was note inside from Lee Lorenz, who was the art editor then, telling me to come back and see him. And I went back and it turned out I had sold a cartoon and he wanted to meet me. And he told me to start coming back in person every week and I was flabbergasted. I was so shocked that it was like this is entirely not what I planned. This is not what I thought was going to happen at all.” So I did. I started coming back and this is essentially now, what is it? Like 40 years later or something? And I’m still working for them. Knock on a bajillion pieces of wood. Drawing cartoons for The New Yorker is a very specific sort of thing. They’re jokes and so it’s about what I’m thinking is funny. Which maybe sometimes I think a cartoon or a joke for me has a little bit of a darker thing also. It’s just more pointed. It's really hard sometimes to describe them because in some ways what the wonderful thing about cartoons to me is that they're this combination of words and pictures. And when I think of like George Booth's drawings, if you just describe what they are okay, it's this sort of middle-aged couple and the woman is in the bathtub and the guy comes in and says, "We need more cat food" or something. It's much funnier when you look at it because you can see all the details. You can see like, you know, that there's a part of the bathtub that's sort of like poking out from the door and, you know, the extension cord … The New Yorker's on a weekly schedule and so my deadline is Monday evening. And so I write stuff down all during the week and I tend to concentrate my New Yorker, like to actually sit down with all my notes and do drawings. I just sort of lock myself in Monday and I'm working like a nut basically all day.. Once I had the idea, I could picture in my head what I wanted to do and then I had to sort of draw it up and play with it. But I like the adrenaline of and the focus of deadlines.- Kampe: THAT WAS AWARD-WINNING CARTOONIST, ROZ CHAST. TO SEE A FEW MORE EXAMPLES OF HER WORK AND HEAR HER DESCRIBE THEM GO TO THE NEA FACEBOOK PAGE, AND, IF YOU’RE IN DC NEXT WEEK, YOU CAN SEE ROZ CHAST LIVE AND IN PERSON AT THE NATIONAL BOOK FESTIVAL ON SEPTEMBER 2. THE NEA WILL ALSO BE THERE SHOWCASING A BUNCH OF GREAT WRITERS AND POETS ON OUR POETRY AND PROSE STAGE. FOR DETAILS, GO ARTS.GOV/NEWS AND CHECK THE ANNOUNCEMENTS.

FOR THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS, I’M ADAM KAMPE.

Music Credits: