Top 5 Blog Posts of 2016: Spotlight on Boise Art Museum

The third most popular NEA blog post of 2016 is our spotlight on Boise Art Museum. Find out how they're bringing the arts and the history of WWII together in one of their exhibits!

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, 120,000 Nikkei (Japanese American citizens and legal resident aliens of Japanese ancestry) from Washington, Oregon, California, and Alaska were forced to move to inland war relocation centers. Minidoka War Relocation Center, located in south central Idaho, saw more than 9,000 evacuees. Although the historic site is no longer active, the memory of those who were incarcerated there, lives on.

Boise Art Museum (BAM), which was founded in 1931, is located 130 miles from Minidoka. BAM has developed a visual arts exhibition featuring artworks produced at the camp or created by artists whose families have a personal connection to the Minidoka incarceration experience. These works of art document memories and perspectives from Japanese Americans, who provide an “artistic representation of the experiences.”

BAM Executive Director, Melanie Fales has more on this new exhibition, which is supported with an Imagine Your Parks Art Works grant.

NEA: You state that most residents are unfamiliar with the history of the Minidoka National site, so what do you hope the community will gain by creating this exhibition?

FALES: Boise Art Museum (BAM) is located just 130 miles away from Minidoka, yet most residents in our urban environment are unfamiliar with the history of this rural site. And even fewer people are aware of the visual art production that occurred at the site during the internment and that has continued to be inspired by this historical event. The project is intended to provide a powerful and personal means to share the perspectives of the artists and to make people aware that the human endeavor of art continues to flourish under adverse conditions. The Museum hopes to open a dialogue with our community and visitors about this nearby National Historic Site and the artistic pursuits that resulted from the single largest forced relocation in U.S. history.

NEA: Can you tell us about the project for which BAM has received the Imagine Your Parks grant?

FALES: BAM has developed a major visual arts exhibition featuring artworks produced at the camp or created by artists whose families have a personal connection to the Minidoka incarceration experience. From October 8, 2016 through January 15, 2017, BAM will partner with the Minidoka National Historic Site to present the exhibition Minidoka: Artist as Witness and related educational programming. By opening an important dialogue about Minidoka, it is anticipated that audience members will gain or strengthen a connection to this significant, historical Idaho site, and the people who were incarcerated there. The goal is for audiences to develop a better understanding of art as a means to document and respond to historically and socially significant events. This project addresses several humanities topics including art history, history, political science, social science and communications.

This exhibition and related programming will aid audience members in understanding and delving into the meaning of works by these artists, and applying this new understanding to the events that unfolded at Minidoka during WWII as well as more recent world events. Additionally, we hope that this project will foster community awareness of the museum as a forum for nonjudgmental dialogue about historic events of universal importance.

NEA: What inspired the development of this exhibition?

FALES: Exhibitions often come about through a series of events that are woven together. Boise Art Museum was in the process of considering a work of art for purchase by artist Wendy Murayama entitled Minidoka, one of the Tag Project sculptures, when we became aware of a body of artwork created at Camp Minidoka that was being studied by a colleague curator. The museum possesses works of art by Roger Shimomura in its permanent collection and Shimomura had been interned at Camp Minidoka as a child. We began discussing possibilities for an exhibition with artworks related to Minidoka when we learned about the new NEA grant associated with National Historic Sites. This seemed like a natural fit and incredible timing, so we decided to pursue the funding opportunity in the hope of realizing our envisioned project.

NEA: How does sharing history and culture through the arts differ from sharing it through other ways such as lectures, etc.?

FALES: The arts convey meaning in an alternative manner to traditional didactic methods. While lectures are valuable as well, the arts have the ability to impart complex feelings, ideas and viewpoints in direct and memorable ways for people of all learning styles and language abilities.

NEA: Could you describe a few of the key works of art that will be featured in this exhibition?

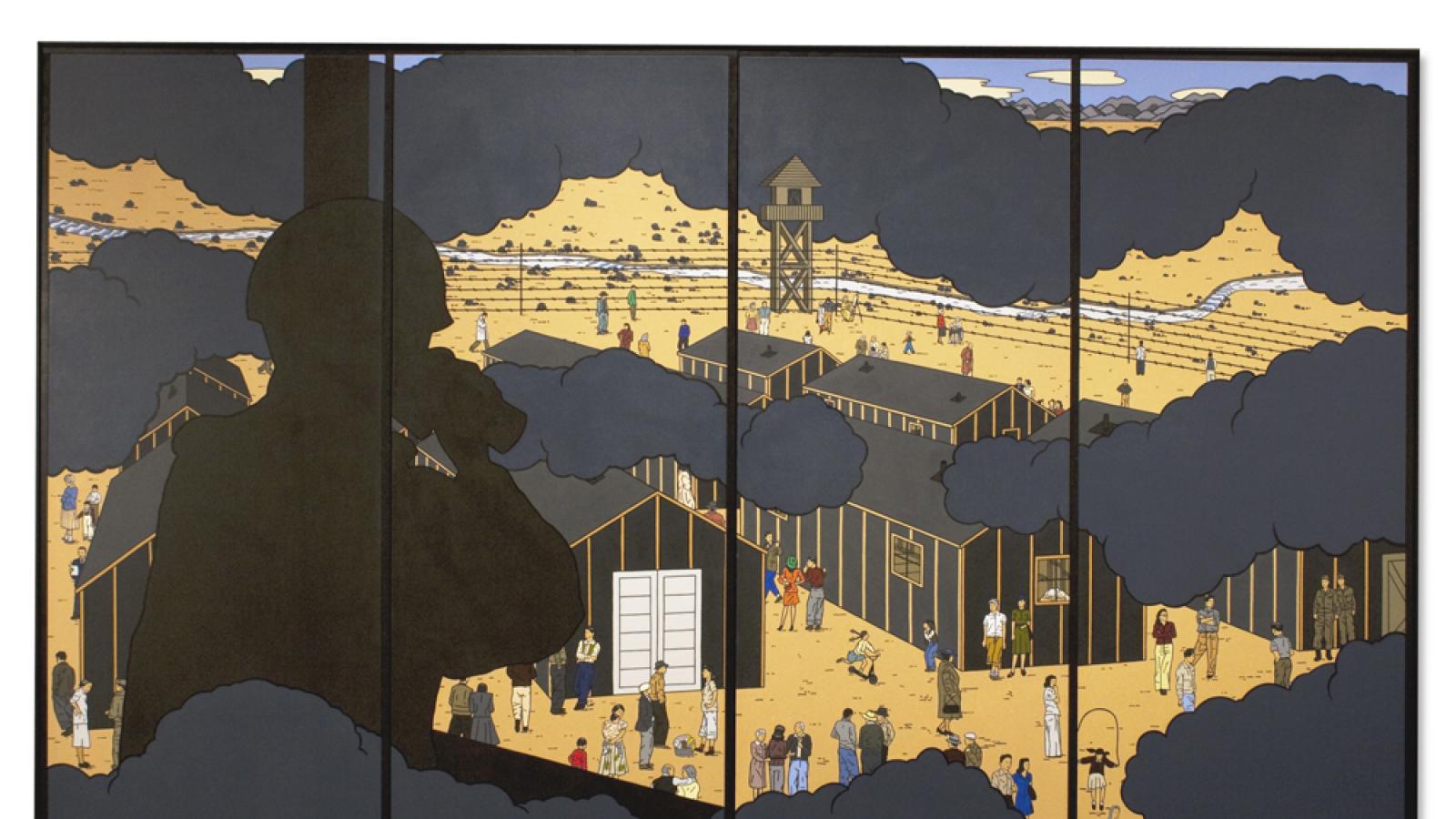

FALES: I will describe two works of art by artists who are both Japanese Americans with personal ties to the wartime experience. Roger Shimomura [who was born in 1939] and his family were incarcerated at Minidoka during WWII. Wendy Maruyama [who was born in 1952] is inspired by her family’s history of being Japanese American in the U.S. during the war. Both Shimomura and Maruyama’s work address societal concerns shared by many cultures, especially xenophobia. In Shimomura’s important large-scale paintings, he recalls memories of his childhood experiences at the camp. For instance, American Infamy #2 depicts Camp Minidoka in Idaho, where Shimomura and his family were detained from the spring of 1942 until the summer of 1944. This painting illustrates the layout of the camp, with an armed guard watching over the barracks and Japanese citizens going about their daily routines. We see playful children, young lovers walking arm in arm, and women and men talking in groups. Other figures are in complete despair – an elderly woman is seated with her head down, while other figures look dejectedly outward through the barbed wire, or pace the compound in a depressed stance. The format of this work is derived from 14th- and 15th-century Japanese Muromachi-era byobu screen paintings that traditionally depict street-scene action through layers of clouds and foreshortened perspective. In this style of Japanese painting the clouds symbolize breaks in time and in this particular painting, the clouds refer to Shimomura’s memory of his childhood experiences at the camp. Shimomura states that the images in his large-scale paintings are, “scraped from the linings of my mind – not necessarily what I remembered specifically, but what I respond to when I think of Camp Minidoka….”

Maruyama’s Tag Project, an installation of 10 large-scale, suspended sculptures, offers a powerful expression of the number of individuals who were forced into incarceration. It consists of 120,000 replicas of the paper identification tags that resemble brown paper luggage tags and that internees were forced to wear when they were being relocated. Each tag bears the name of one internee, and the tags are grouped into ten sculptural bundles and suspended from the ceiling. Each bundle represents one of the camps. They evoke a powerful sense of the humiliation endured by the internees and the sheer numbers of those displaced. According to Maruyama, as she researched her family history and looked through documentation of the camps, “The most haunting and striking photos were of the families wearing tags at the various assembly centers before being shipped off by train to these remote areas. Every man, woman and child was issued a tag with their name, a government-issued number, and the destination camp. I realized the tags were emblematic of the experience, so I decided that I would create The Tag Project. I wanted to recreate all the tags for every Japanese American that was interned during 1942.” In completing the project, she not only addressed Japanese-American internment, she also saw relevance to 9/11, the treatment of Muslim Americans, and changing immigration laws. In her 2013 TEDx talk in San Diego, she said, “It taught me as an artist to be able to rethink my process. How can I use my art to do more than just be pretty?”

NEA: Why is it important to preserve cultural/historical sites?

FALES: This historic site documents a painful time in American history and Idaho history. The monument helps ensure that the individual people who lived in Minidoka do not disappear from memory and communicates a story that fits into the larger human history of our nation and world. It conveys aspects of perseverance and resolve among the Nikkei community and reminds us of past events so that we have a better understanding of our past and informed perspectives for decisions in our present and future.

NEA: The Minidoka National Historic site is one of hundreds of units of the National Park system. How is this exhibition and site unique?

FALES: This exhibition will showcase the artistic pursuits at this historic site as well as those that have taken place after WWII as a result of the internments at this site. This is the only internment camp site in the state of Idaho and it remains a relatively unknown part of our Idaho and national history. The unique project provides the opportunity to link the artistic representations of the experiences and their lasting implications to the historic site in a way that has not been done in the past.

NEA: How is NEA’s grant important to the Minidoka National Historic Site project?

FALES: BAM is sensitive to the fact that people have mixed feelings regarding the actions of the U.S. government during WWII. We want to facilitate the opening of a dialogue about the events that occurred in our state during that time. The museum is not taking a stance, rather we intend to present a safe space for artists and audience members to discuss the events that took place, focusing on the artistic process of documentation and response. We want to present a balanced approach to a challenging topic. For topics such as this, which can be considered potentially controversial, it is not always possible to garner funding from local sources. The significance of this discussion is evident at a national level, and we are grateful to the NEA for recognizing its value. This funding makes it possible for the museum to carry out the project for the benefit of our community and country.

NEA: Fill in the blank. The arts matter because…

FALES: They are the enduring and tangible forms of communication that tell the stories of our society. They communicate across cultural and language barriers and promote tolerance and understanding among people. They are of our time and place and have been a necessary part of expression since human beginnings.