Art Talk with Erin Entrada Kelly

Acclaimed children’s novelist Erin Entrada Kelly will tell you honestly that she prefers children over adults because, in her eyes, she’s still kind of like a kid. Kelly discovered her connection to young people and her knack for writing children’s literature when she wrote a collection of short stories in her 20s, unearthing a uniformity in her work—all of the characters were ages 8-12. Reflecting on her own childhood, Kelly said, “That age was a very difficult time in my life and I think whenever we go through a difficult period of our lives we tend to remember what it felt like even years later.” Kelly grew up as the only Filipino-American in a small community in Louisiana, which made her feel different from her peers and, at times, isolated. Gleaning from her own experiences, she uses her heritage and her adolescent struggles to craft characters and themes in her stories with hopes of helping children feel “less alone in the world.”

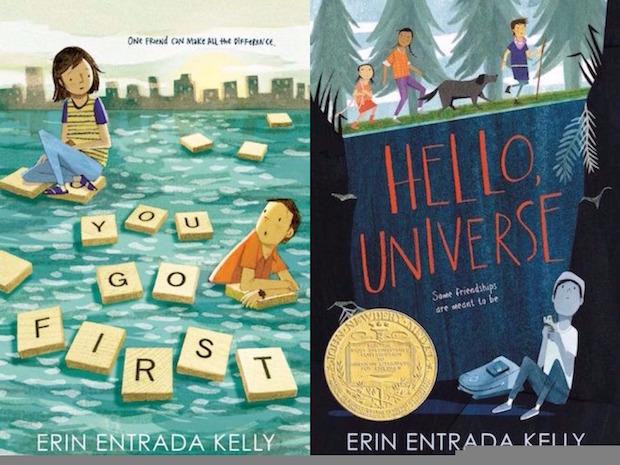

Kelly has written four children’s novels that share a common thread of loneliness. Her most recent book Hello, Universe, which won the 2017 Newbery Medal, address issues—like social isolation and bullying—and in her newest book, You Go First (coming out April 2018), the premise is that no one struggles alone. Although her work has received numerous awards, Kelly says her proudest moments are learning of the impact her work has made on her young readers.

Here is Kelly on how her affinity for both storytelling and middle schoolers intertwined, leading her to fulfill her life’s purpose.

NEA: When did you fall in love with storytelling?

ERIN ENTRADA KELLY: I was about eight years old in second grade when I started writing, and I've always been a reader. I can't remember a time in my life when I wasn't reading books. At some point, it occurred to me that books were basically words on paper and then it occurred to me that I had paper, and I had a pencil, and I could just create any story I want. Whenever I talk to kids I tell them the most powerful thing about stories or art is no matter what, you're putting something out there in the world that didn't exist before. I was really drawn by the idea of creating another world where anything that I wanted to happen could happen, and it's just never left—if anything, it's gotten even more palpable.

NEA: What led you to pursue a career as a children’s novelist?

KELLY: In my 20s when I started really trying to write a full-length novel, every time I would start a book I could never finish it. It would always just kind of fizzle out after about 50 pages or so. I couldn’t figure out what was going on, so I started writing short stories, and I realized that almost all of my short stories had characters between the ages of eight to 12. I thought that’s really interesting that there’s something about that age group that really draws me in. I started reading middle grade, and I started writing middle grade, and it really came so naturally to me. I think because that age was a very difficult time in my life, and I think whenever we go through a difficult period of our lives we tend to remember what it felt like even years later.

NEA: What do you love most about writing for young readers?

KELLY: I really prefer children over adults because they're really interesting to me. For one thing, they're incredibly honest, which I love. For the most part, they haven't been completely jaded or made cynical by the grownup "world." But by the same token, their world is very real because they are going through so many different things. The way they persevere and their resilience always amazes me. When I speak to adults you can always kind of predict what questions you're going to be asked, but when you talk to kids you know there's always going to be some random question that's going to pop up just because their filter is a lot different than ours as adults, which I find so refreshing. And also, they have such an incredible energy about them. Whenever I go on tour—and its two schools a day for a week in a different city—when I walk into the school, I'm exhausted. I can't remember what city I'm in, or where I am, but as soon as I'm in there with the kids my adrenaline just shoots up, because they're so energetic.

NEA: Who were you reading when you were young?

KELLY: I was reading a lot of Judy Blume. Judy Blume was my hero, and she still kind of is.

NEA: When did you start doing school visits and how have those visits fueled your work?

KELLY: After Blackbird Fly came out in 2015, I got a few Skype requests. Kelly Farnsworth who is with the Eduprize School in Gilbert, Arizona, was the first person to request a school visit from me. I was so excited and then it gradually started picking up from there.

I like to say as I’m speaking [that] if students have questions they can raise their hands because I love the Q and A portion of my talks—it's my favorite part of the whole presentation.

Some of the kids that I see when I’m up there speaking will plant a seed in my brain. For example, if I'm up there speaking, and I see a girl wearing bunny ears and holding a bunny stuffed animal, that's something that might stay in my head. Or if I see a kid who is dressed to the nines as if he's going to church or something, but it's a regular day at school, that's something that will stay in my head.

Another way the school visits energize me and inspire me is when they tell me their personal stories. A lot of times they'll come up to me afterward and tell me a story about when they were bullied, or something about them personally. Sometimes these kids haven't even read my books, but they just felt comfortable enough after I spoke with them to come up and tell me something personal about themselves. It just makes me feel like, okay, this is where I need to be. It reminds me that I'm doing what I need to do, what I want to do, and that it's my purpose.

NEA: In Hello, Universe the characters Virgil, Kaori, Valencia, and Chet are all so distinct and different that they seem to cover scenarios for all types of young readers. Is this something that you are mindful of when you are writing a book, creating diverse and relatable characters for your readers?

KELLY: It's something that I'm aware of, but I'd never want to force some kind of character into a book unless it makes sense to the story. All of my stories start with a character or an image of a character, and they build out from there. In the case of Hello, Universe, I had an image of a boy who's trapped in a dark place, and he's afraid, and he's calling for help, and there's a girl, but she can't hear him, and that's how Valencia came to be. But I never sat down and said, "I'm going to write a character who is deaf, and I'm going to write a character who is Japanese American." It doesn't really happen that way. It's more organic than that. So, Valencia turned out to be a character who was deaf, because that was the image that I had in my head, and Kaori is Japanese American. I didn't purposely say, "I will insert a Japanese American in here," but whenever I imagined her that's how she came to me in my head. I guess it's something that I'm definitely mindful of, but the characters come to me as they come to me, so in this case, they all came to me in very different ways.

NEA: Do you use a similar process when picking themes for your stories? Do they just come to you as you’re writing and developing the story?

KELLY: Once I have an image of a character that stays with me, I ask myself; “Why is that character in this situation? What is this character doing?” I'm very organized as far as my books go. I'll sit down and do an outline. I'll do a chapter summary, and the story kind of develops from there. Pretty much every time the outline will change because characters take us to places we don't expect. That's usually how the story develops, and the characters develop.

NEA: Hello, Universe features a young Filipino-American boy, Virgil. As an author, in what ways are you drawing from your own childhood and heritage as a Filipino-American?

KELLY: I grew up as the only Filipino in my community, so it took me a long time to embrace my ethnicity and my background. I was born in the States; I'm first generation. One of the things that I wanted to do with Virgil, and with the books before it, is celebrate and showcase Filipino culture by introducing foods that I ate, words, colloquialisms. When I was a kid my grandparents from the Philippines lived with us for a while, so I drew on some of that. I just think it's really important for people to be introduced to many different cultures, and unfortunately, I mean, the tide is changing a little bit, but Filipino culture isn't something that's necessarily prevalent in western literature, especially for kids.

NEA: You said, “It took you a long time to embrace your ethnicity and background.” At what point did you start including your heritage in your storytelling?

KELLY: Actually, what really set me off writing short stories was my mother told me a story about my grandfather. I wrote it as a short story, and it got rejected. I got one rejection letter back, and it said, "We're sorry we can't publish this, but you were in the final cut." Now, I took that letter, and I framed it. Most people would say, "Why are you framing a rejection letter." I tell people that it’s not a rejection letter. It’s a win, because that tells me, okay, you're on the right track, like you are almost there. I still have it framed to this day. I asked my mom for more stories and then I started writing short stories that were set in the Philippines, that had Filipino characters. My first short story I ever sold was to Story Philippine, which is now defunct, but it was a fantastic literary magazine printed in the Philippines. All of my books thus far have had Filipino characters, and Filipino heritage. You Go First was the first one that has not.

NEA: What do you hope your readers take away from your novels?

KELLY: My hope with each of my books is that at the very least for the time that they're reading the book, or that they're with the characters, they feel less alone in the world. My bigger hope is that when they put the book away it stays with them, and changes them, and evolves their world view. I mean, that's the big wish, but the small wish is at the very least they know they're not alone because that's what important to me. All of my books have loneliness as a common thread because I was a very lonely kid. So I liked that idea of them feeling like, okay, there's someone out there who understands me, or there are other people out there who feel the way I do. I've been saying my thesis statement for You Go First is we never struggle alone. When I was a kid, I used to think, are there other kids out there who are sad like me, or lonely like me? I would think about all the kids in the world, like other kids in other countries who feel sad like me, and I'm never going to get to meet them. I would be so sad because I thought they could be my best friend, and I'll never know. I'll never meet them. Meanwhile, there were people in my school, obviously, who probably thought exactly as I did. It doesn't feel that way when you're a kid. With You Go First that was kind of the big idea that I had; that across many miles, across an ocean, across the classroom, there's someone out there who is going through the same things you are. Even if you don't ever know it or don't ever meet them, just knowing that can be a comfort for people.

NEA: What have been some of your proudest moments as a writer?

KELLY: Winning the Newbery Medal for Hello, Universe would definitely be up there. I'm going to be honest with you. The proudest moments are when I get letters or e-mails from kids that are very personal. They're telling me something about my book, like that they had been bullied too, and now they’ve learned to stand up for themselves. One girl told me that she read Blackbird Fly and she asked a girl to sit with her at lunch, a girl who sat alone at lunch every day. I got this great letter from a kid—it was two pages long. Basically, he said I'm different, and it's okay, and now I know it's okay to be different.

I mean, it's great to get excellent starred reviews from Kirkus, School Library Journal, and Weekly, and all that stuff. But when you hear it from kids that's when, you know you’re doing the right thing.

A question that adults ask is, “How many books have you sold?” I'm like I have no idea. I mean, I honestly don't. I'm not going to say I don't care about that. Obviously, I care in a way that I want to make a living, but I'm always thinking about the kids first. That's my number one goal is to write books for kids that are honest, and that are meaningful to them. All this other stuff is like just like the icing on the cake.