Grant Spotlight on Crow's Shadow Institute of the Arts

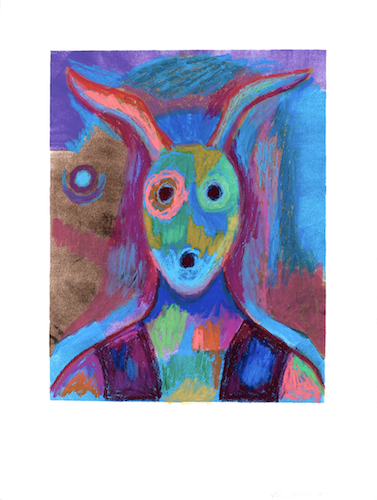

Jim Denomie (Ojibwe) in residence at Crow's Shadow, 2011. Photo by Pat Walters

Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts (CSIA) was founded more than 25 years ago with the vision of helping creative people on the Confederate Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Pendleton, Oregon, move forward with their work by providing an infrastructure via professional development and other related activities. In 2001, CSIA refocused its mission, becoming a center for printmaking and publishing by Native artists. Today Crow’s Shadow hosts three to five artists each year—from painters to poets to sculptors and photographers—who work with a master printer to engage in their art practice from a new perspective through the practice of printmaking. Crow's Shadow recently received an NEA grant to support its printmaking residencies. We spoke with CSIA Executive Director Karl Davis to learn more about the project.

NEA: Sometimes we have a limited idea of what it means to be a contemporary Native artist and are surprised when these artists are not directly working in traditional art forms.

KARL DAVIS: There are traditional elements to [contemporary Native art], but it’s not always traditional. When we bring artists to Crow’s Shadow, they’re artists first. Their background, heritage, ancestry might be Native, but they’re coming as artists. I think contemporary art, it’s so vast. There are so many different things that people are doing all over the world. Having a Native-focused residency, people do tend to think that there might be more traditional-based imagery in the work that’s produced. But art is an experiential process, and the people who make the work are making work based on their experiences.

There’s not a monolithic Native experience. It’s very diverse even across North America. So to present the work that is produced here as individual unique experiences is very eye-opening for a lot of people. We’re one of the only professional print studios on a Native-American reservation in North America, so it is a unique experience for people.

NEA: Why do you think that this particular project is necessary?

DAVIS: I think it’s really important to continue bringing contemporary Native artists into the studio space to bridge a lot of different processes and approaches and also to show the students that we have working here on a regular basis from the reservation… that creative avenues are viable economic futures for people. It doesn’t have to be a hobby. It doesn’t have to be something they did as a kid and then forget about. They can pursue [the arts] possibly as a future career. I think that’s really important to a lot of young students that are here on the reservation to see the different possibilities of what can happen that they might not know about.

I think the most important aspect of what we’re doing is offering a professional print studio to contemporary Native artists and that is not always an easily accessible thing. Giving that time and space to somebody to experience new work, new processes, is very important. And the idea of cross-pollination for artists and communities is very important to what we’re doing.

NEA: How does the CSIA artist residency work?

DAVIS: We will select artists over the next few months and invite them to Crow’s Shadow for a two-week residency. They’ll work with the master printer in a collaborative process: the artist is the creative engine of that and then the master printer is the technical expertise…. After the artist is gone, the master printer and press assistant will publish the work. [While the artist is in residence] there will be a community-based project or component to the residency. It will be dependent on the artist themselves, but [it will be some] sort of a workshop, lecture, or community-based event that will include the people from the reservation and the outlying areas to bring that community spirit into Crow’s Shadow.

NEA: Can you share some examples of community-based projects that resident artists have done before? And also talk about why it’s important to have a community-focused part of this residency?

DAVIS: In our vision and goals, one of the aspects of what we really hold dear is the idea that we bring the reservation to the world, but also the world to the reservation. So through bringing artists into Crow’s Shadow from outside the area, we get a sense of this cross-pollination of artistic and creative endeavors. Having a community-based project during the residency is very important to allow the community into the space while the artist is working [so they can] see different types of artists, different approaches to creativity. We’ve had artists that have done youth workshops. We have an artist whose primary process was collaging, and there was a day-long workshop where the students were given magazines and taught how to collage. We’ve had other artists who worked both in contemporary art as well as traditional art. We’ve had artists who taught sewing and blanket-making projects. We worked very closely with an artist named Marie Watt in the past, [and] a lot of her work is community-based in general. She did a sewing circle while in residence. Bringing the community into Crow’s Shadow during the artist’s residency is really important to get that sense of community that goes beyond just the walls of Crow’s Shadow, beyond the reservation, and among indigenous Native people across North America and the world, too.

NEA: CSIA also documents the artist residencies through audio and video. Why is that important?

DAVIS: Documenting the process is really important to allow people to see some insight into what the artist is doing and their thought process. For people who have never seen printmaking happen, that is also really important because it’s a very specific technical process. We use a lot of photo-sensitive aluminum plate lithography, which is itself a very distinct, unique process. Having people be able to see the creative aspects of it and how that image is generated and then also published and produced is I think is valuable for artists and non-artists alike. [We have] an archive available so that future research and things like that can take place. We don’t work in a vacuum, so being able to present that work to future historians and research is also important.

NEA: I know in addition to working with the artists-in-residence, the master printer also engages with local students as part of your community outreach.

DAVIS: We do work very closely with what’s called Nixya’awii Community School. That’s the charter high school here on the reservation. It’s part of the Greater Pendleton School District, but it was founded on the reservation for primarily tribal use. About five students a year participate in a program [through which] they attend a weekly class here at Crow’s Shadow working with the master printer. They’re learning all aspects of printmaking. So they’ve done linocut relief printmaking and monotyping. They’ve done a little bit of lithography as well and are focused now on screen printing. At the end of the school year, they do an exhibit of their work in the studio…. They price and sell the work on their own, and they receive a hundred percent of the sales from those prints. It’s really inspiring to me and to the Crow’s Shadow staff to see the students be able to get the experience to learn new outlets of creativity. When the artists are in residence and [the students] get to interact and interface with those artists, [that is] really key to the kind of holistic approach that we have in our programming between the traditional arts programming that we do, the educational aspects, and then the residency parts of it, too. They’re all interconnected in some way.

NEA: How important is funding from the National Endowment for the Arts to this project? What does it make possible?

DAVIS: The grant through the NEA is absolutely vital to continuing to be able to offer paid residencies to artists that will be taking time off from their other endeavors, their other studio work, their other jobs. The funds through the NEA are key to keeping that a positive experience for people and being able to supply that time and space for them to continue or experience new art-making processes.

NEA: What does success look like for you with this project?

DAVIS: When an artist is here working in a studio, and you see that their creative gears are running… I think that’s very successful. Then when the prints are produced and published, and… people are interacting with the work in really positive ways. The long-term success is that that artist might take what they’ve learned or done in the studio here and may return to their home studio, to their community, and integrate some of what they might have learned here into their new practice or in some way utilize what they’ve done here into their future art practice.

Interested in hearing first-person from other NEA grantees? Then you may like our stories on Louder Than a Bomb Youth Poetry Festival, St. Louis Classical Guitar Society, and Cathedral Arts Project. Select “Grants” from the Categories drop-down menu for even more great stories.