Celebrating Black History Month with the National Portrait Gallery

When the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) was established by Congress in 1962, its founding legislation dictated that the museum was limited to collecting paintings and statuary. As NPG Assistant Curator of Photographs Leslie Ureña pointed out, “the history of portraiture is for the elite, so we had therefore, a limited number of people that we could [include] that way.” These people were by and large Caucasian, as was of course the entirety of the America’s Presidents collection—a major feature of the Portrait Gallery—until Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of President Obama was unveiled in 2018.

With the eventual expansion of the museum’s collection to photographs, prints, and drawings, a broader, richer swathe of American history was put on view, and the museum’s galleries began to more fully reflect the country’s many peoples and cultures. This has been coupled with special efforts to approach new acquisitions with a nuanced view of American history, as well as with programs and exhibitions that highlight historical gaps in portraiture in innovative ways. For instance, through exhibits such as the recent UnSeen: Our Past in a New Light, Ken Gonzales-Day and Titus Kaphar, “we find out who isn't represented in portraiture, and how we can explain that,” said Ureña, while the current show Black Out: Silhouttes Then and Now showcases silhouettes, which were traditionally available to those usually excluded from historical and visual records (for instance, the exhibit includes silhouettes of an enslaved girl and a same-sex couple). There is also the museum’s Identify series, which invites performance artists to highlight “the absence of different figures in our collection,” said Ureña.

In these ways, the NPG has sought to give Americans of every race, class, gender, and sexuality their proper due in history. “It's important for us to show that we are a country that's come to have many, many histories,” Ureña said. “And we’re complicating history by trying to find different histories as we go through and collect.” In honor of Black History Month, we recently spoke with Ureña about a selection of the museum’s portraits of Africans Americans, all of which are currently on view.

Frederick Douglass by Unidentified Artist, c. 1844. Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Frederick Douglass

Born into slavery, Frederick Douglass escaped from Maryland’s eastern shore and settled in Massachusetts, where he became a prominent abolitionist, public speaker, writer, and advocate for women’s suffrage. Douglass published his first autobiography in 1845, which revealed the details of his enslavement and thus necessitated a temporary move to Europe for fear of reprisal from his former owner, Hugh Auld. Friends in Europe raised the funds needed to purchase his freedom, and he returned to the United States, where he continued his advocacy until his death. According to Ureña, this painting was made around 1844, and is possibly based on the engraving used as the autobiography’s frontispiece, which itself may have been based on a daguerreotype. The museum also has several daguerreotypes of Douglass in its collection. Ureña noted that while Douglass was happy to be photographed—he is thought to be the most photographed man of the 19th century—he didn’t like to sit for painted portraits, as he was concerned a non-African-American painter might have “absorbed the conceits of depicting African-American stereotypes that might come out in the painting,” she said.

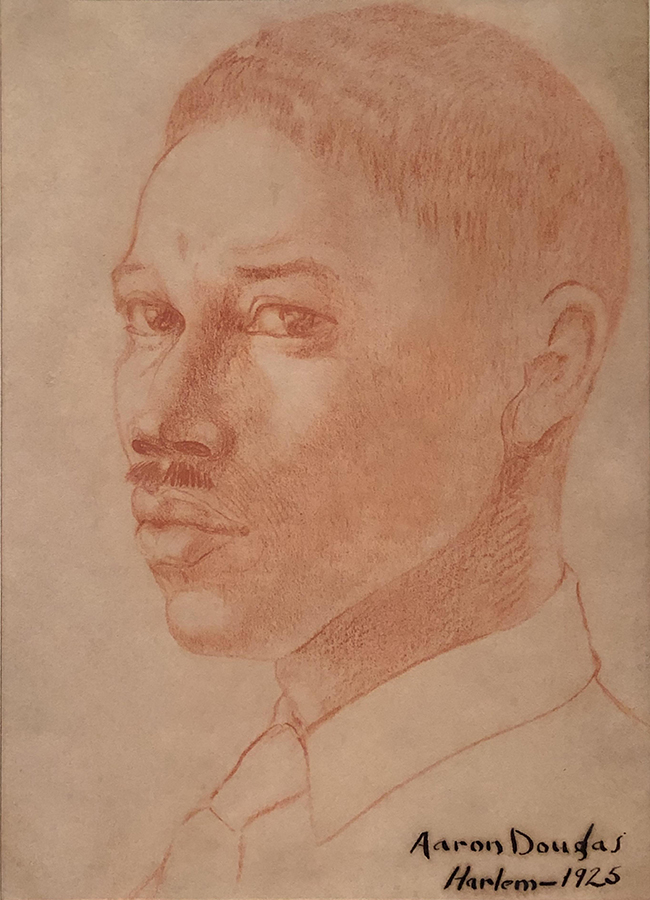

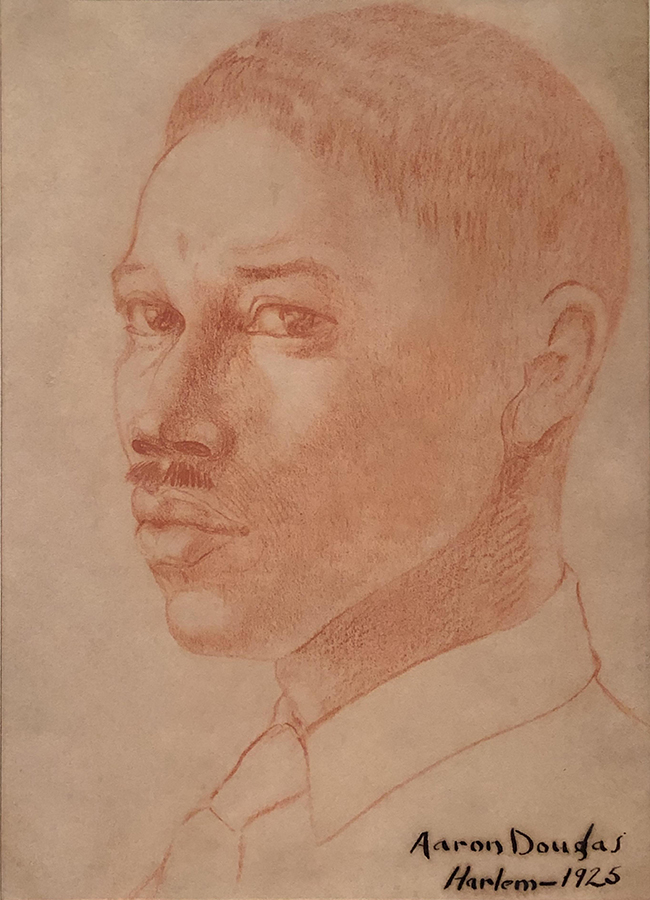

Aaron Douglas by Aaron Douglas, 1925. Red conte crayon on paper. Gift of the Abraham and Virginia Weiss Charitable Trust, Amy and Marc Meadows, in honor of Wendy Wick Reaves.

Aaron Douglas

Douglas drew this self-portrait in 1925, the year he left Kansas City and stopped in New York on his way to Paris. It was a fortuitous layover: he was “swept up in the excitement of the Harlem Renaissance,” said Ureña, and stayed for two years. He became a leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance, and developed a distinctive style that combined a modernist aesthetic with African motifs. Ureña noted the contrast between many of his paintings and this delicate self-portrait, done in red conte crayon.

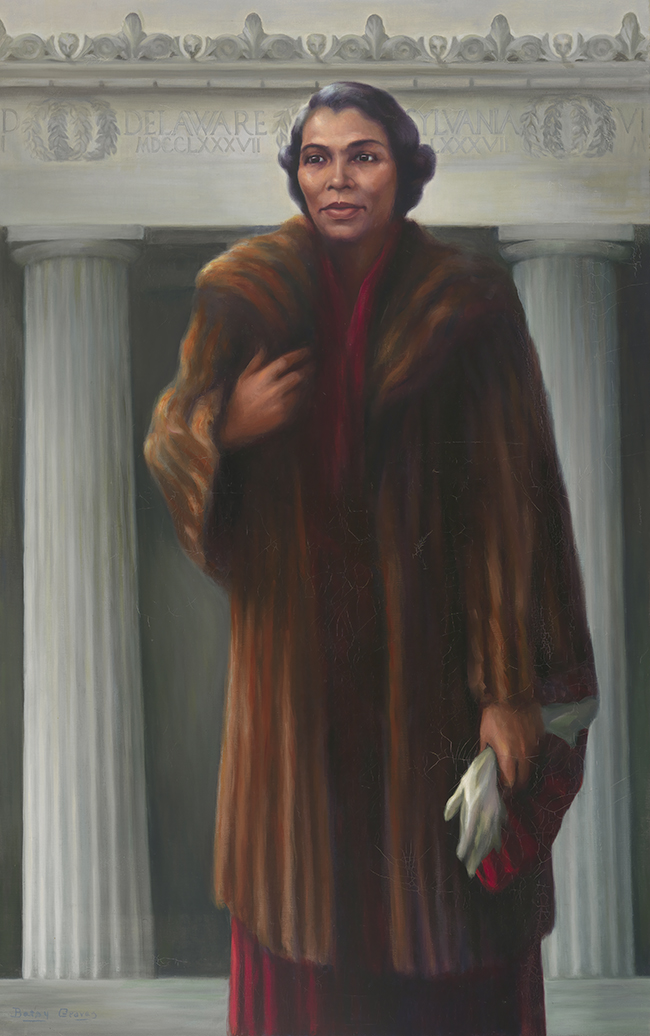

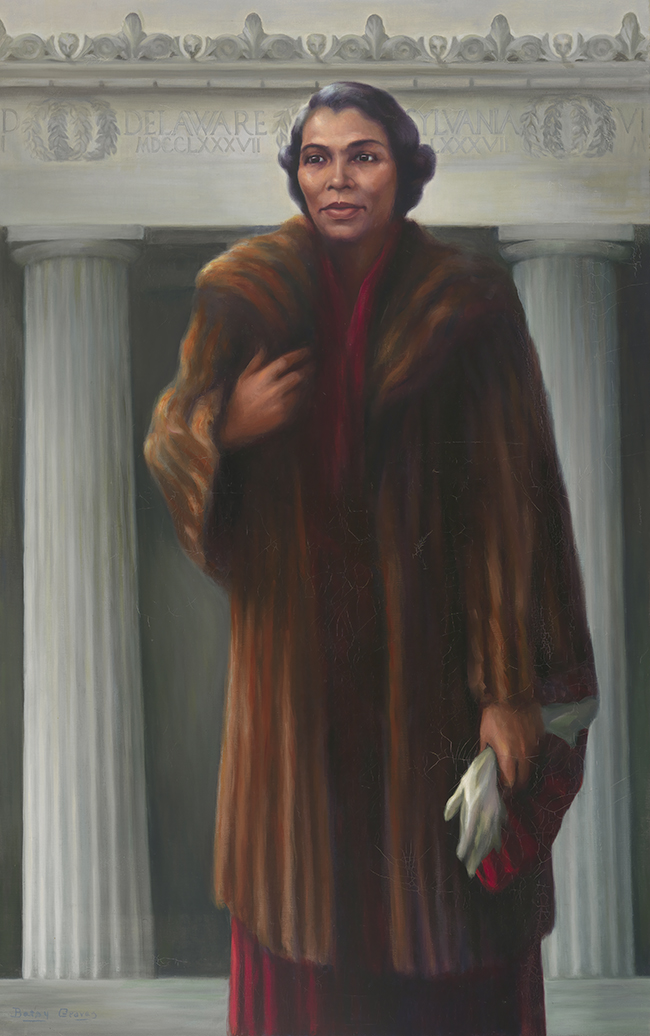

Marian Anderson by Betsy Graves Reyneau, 1955. Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of the Harmon Foundation © Peter Edward Fayard

Marian Anderson

Although painted in 1955, this painting of Marian Anderson references 1939—the year Anderson famously sung on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial after the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to let her perform at Constitution Hall on account of segregationist rules governing the performance space. Betsy Graves Reyneau used newspaper clippings and other images to create this painting, which was commissioned by the Harmon Foundation, which supported and celebrated the creative and cultural achievements of African Americans. In addition to Anderson, the foundation commissioned 49 other portraits of notable African Americans for a traveling exhibition, with the express purpose of countering racial stereotypes through portraiture. The museum will offer a fuller look at Marian Anderson in its One Life: Marian Anderson exhibition, which opens June 28.

James Farmer by Alice Neel, 1964. Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Hartley Neel and Richard Neel © 1984, Estate of Alice Neel

James Farmer

Alice Neel painted this portrait of James Farmer in 1964—the year the civil rights leader saw three members of his Congress of Racial Equity (CORE) murdered in Mississippi. A founder of CORE and the man who established the Freedom Rides, Farmer is portrayed here as “full of anger,” according to Neel, as he confronted the question of how the response to the civil rights movement’s nonviolent actions could be so murderous and full of hate.

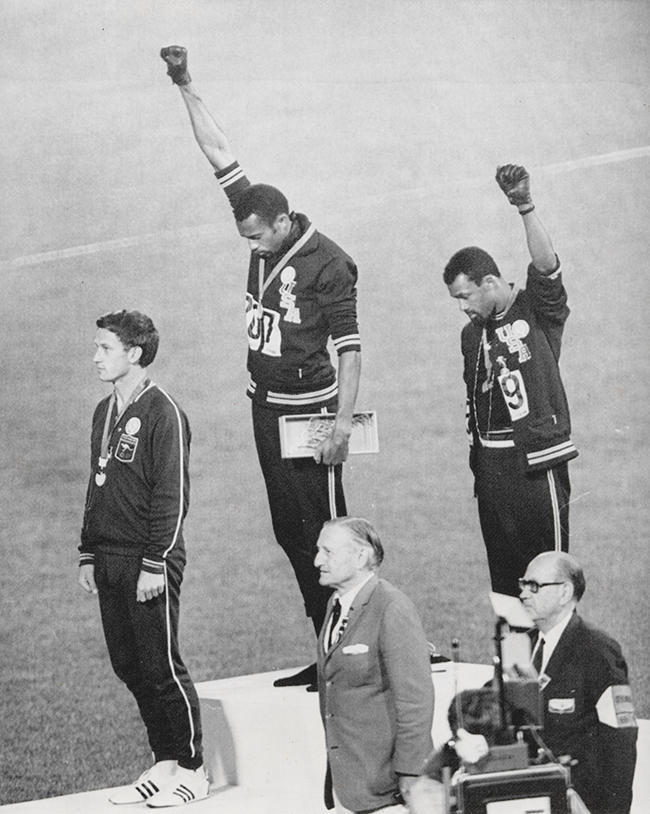

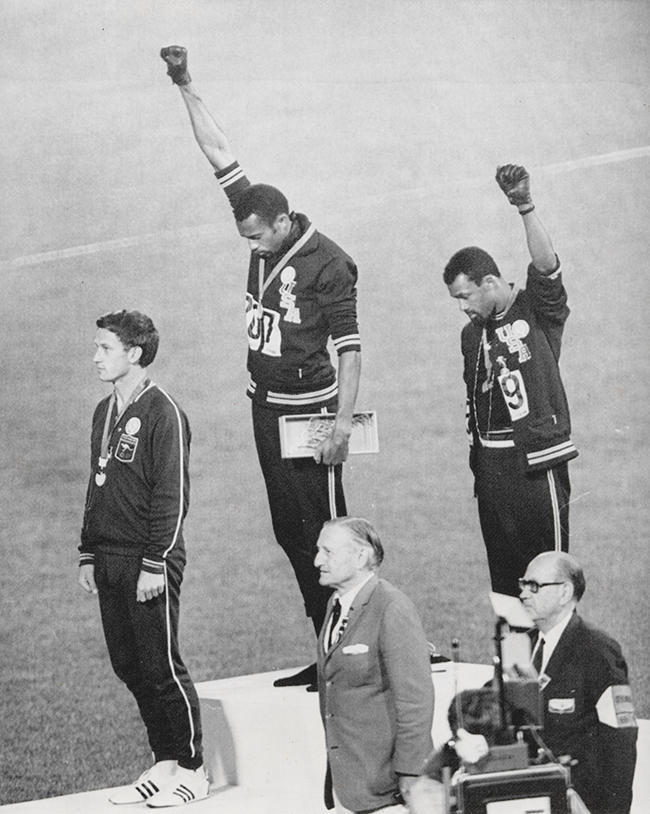

Tommie Smith and John Carlos by Unidentified Artist, 1968. Gelatin silver print. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; acquired through the generosity of David C. Ward.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos

While this particular frame is uncredited, the image is instantly recognizable: the moment Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in protest as the “Star-Spangled Banner” played during the 200-meter medals ceremony at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Ureña said it was one of the first times sports had been politicized, and the repercussions were immediate: both men were forced to leave the stadium and were dismissed from the U.S. track team.

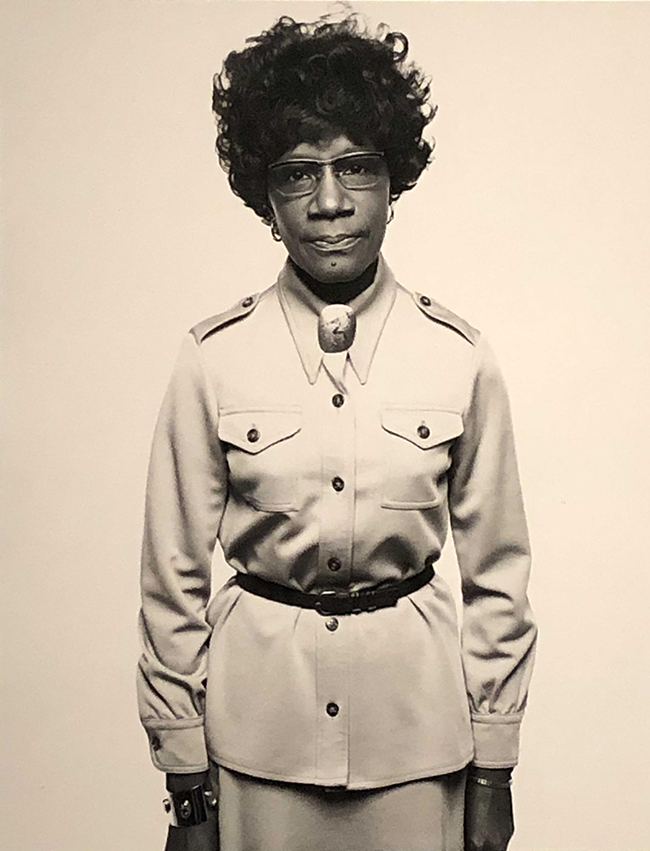

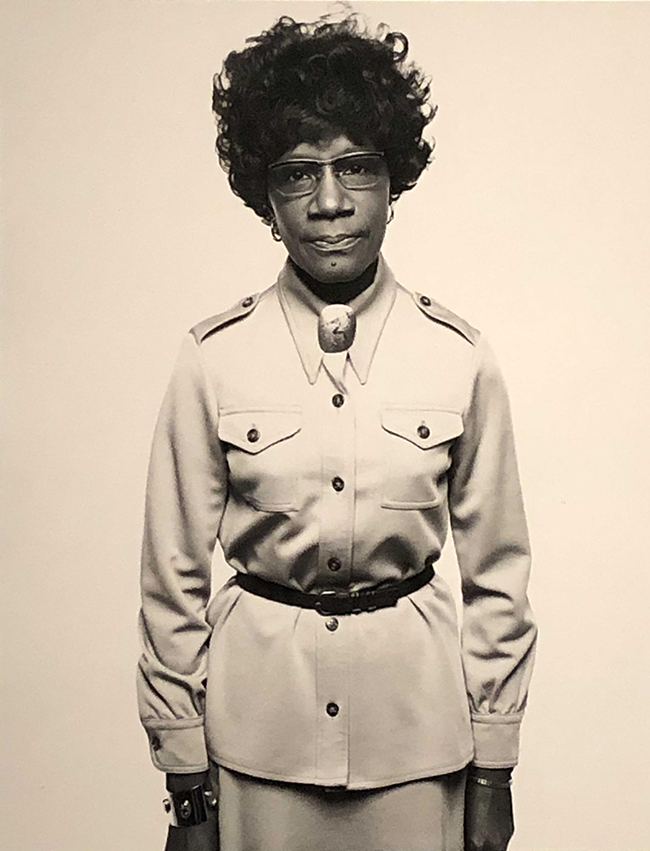

Shirley Chisholm by Richard Avedon, 1976. Gelatin silver print. Acquisition made possible by generous contributions from Jeane W. Austin and the James Smithson Society.

Shirley Chisholm

This photograph of Shirley Chisholm was part of Richard Avedon’s 1976 Bicentennial series, which captured the era’s most powerful people and eventually ran in Rolling Stone. Chisholm was the first African-American woman elected to Congress, and also ran in the Democratic presidential primaries in 1972, inching the needle forward toward equality both for African Americans and women. While the Avedon photograph was the first Chisholm portrait acquired by NPG, several others have entered the collection since then.

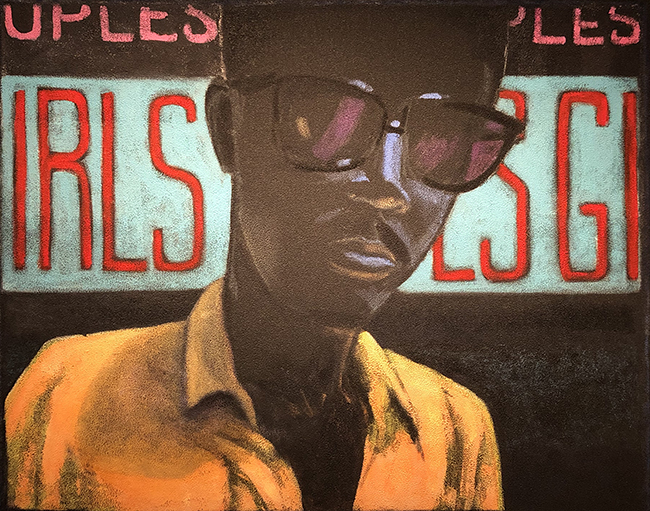

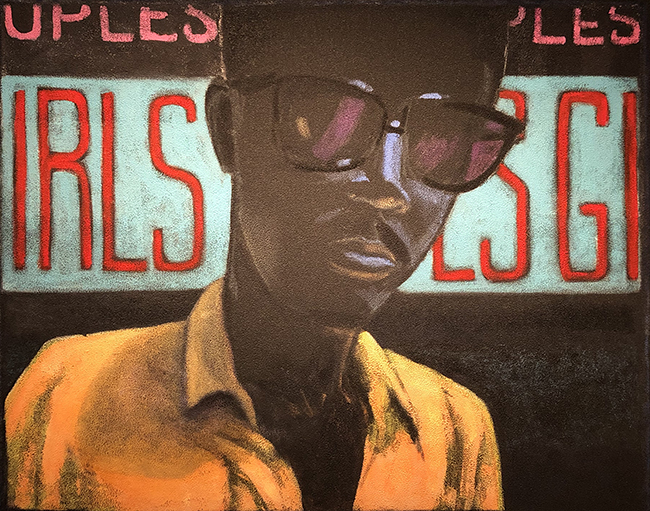

Fab 5 Freddy by Jane Dickson, 1982. Acrylic on canvas-backed vinyl.

Fab 5 Freddy

Taking his name from his involvement with the Fabulous 5 graffiti crew, Fab 5 Freddy was a pioneer of hip-hop music, and one of the first people to bridge the street art and underground music scenes with the mainstream art world. He organized gallery shows for street artists in downtown New York, and became the first host of Yo! MTV Raps in 1988. In this 1982 portrait, his friend Jane Dickson captures the gritty New York of the 1980s, complete with a rough texture and risqué signage in the background.

Henrietta Lacks by Kadir Nelson, 2017. Oil on linen. Collection of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery and National Museum of African American History & Culture, Gift from Kadir Nelson and the JKBN Group, LLC © 2017 Kadir Nelson

Henrietta Lacks

There is no one way to change the course of history; sometimes, one’s impact is entirely unintentional or even unknown. Such is the case with Henrietta Lacks. In 1951, Lacks visited Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital with bleeding, which was eventually diagnosed as cervical cancer. Although Lacks passed away a few months later, the cells that were taken from her tumor—without her or her family’s knowledge—didn’t die, but instead doubled every 20 to 24 hours. This made them invaluable to researchers, and the “HeLa” cell line, as it is today called, has contributed to the development of the polio vaccine, in vitro fertilization, gene mapping, and other medical breakthroughs. Despite this, Lacks’s personal story and the ethical issues surrounding her cells have only recently come to light, revealing the complex human and social histories entwined within the study of medicine. This portrait is rife with symbolism: the missing buttons on Lacks’s dress represent the extracted cells; the wallpaper’s flower of life pattern represents immortality; and Lacks’s yellow hat is meant to resemble a halo.