A New Exhibit Pays Tribute to Marian Anderson

The image is iconic: Marian Anderson, one of the most celebrated contraltos of her day, wrapped in a fur coat, singing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday 1939 before 75,000 people. With the help of Eleanor Roosevelt, the concert had been arranged after Anderson was barred from singing at Constitution Hall before an integrated audience, a move that prompted hundreds of women—including Roosevelt—to withdraw their membership from the Daughters of the American Revolution, which owned the venue. Considered a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement, the Lincoln Memorial concert was a symbol of triumph over oppression, and a sign that the human spirit was more powerful than the efforts meant to diminish it.

But for many of us, our knowledge of Marian Anderson begins and ends with Easter 1939. This was the case for Leslie Ureña, associate curator of photographs at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG). But after beginning preliminary research into Anderson’s life, she quickly realized there was a much bigger story to tell. She said, “I wanted to look at that story and expand it beyond ’39.”

The result is One Life: Marian Anderson, on view at the NPG through May 17, 2020. Curated by Ureña, the exhibit is part of the museum’s One Life exhibition program, which focuses on a single figure from American history.

The exhibit begins with an early baby photo of Anderson in Philadelphia and ends with a photo of her shortly before her death at age 96. In between, there are photos, paintings, and objects documenting defining moments, from when she became the first black performer to sing at the Metropolitan Opera, to her acceptance of the NAACP Spingarn Medal for outstanding achievement, which was presented to her by Eleanor Roosevelt. It is a life that both shaped history and was shaped by it, encompassing broader issues such as the role of music in the Civil Rights Movement, the influence of racism in the arts, and the history of segregation in the United States.

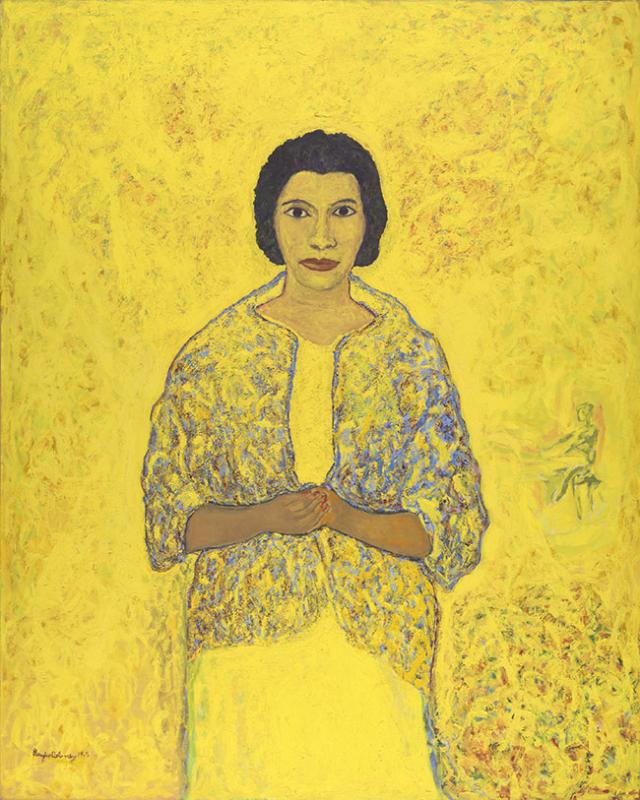

Marian Anderson by Beauford Delaney, oil on canvas,1965. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, J. Harwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund for American Art. Photo by Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator

Although Anderson was reluctant to discuss or celebrate her role in the Civil Right Movement, the exhibit makes clear that her many achievements and “firsts” were instrumental to the struggle. “[The exhibit] looks at the overview of her career and how these smaller moments can have an impact as a cumulative effect,” said Ureña. “Every step of the way is an incremental step to breaking down different barriers.”

Anderson was born in Philadelphia on February 27, 1897, where she sang in her church choir. Although her gift for music was evident early on, she was turned down by several white voice teachers and an all-white music school, where she was not allowed to even submit an application. Her community rallied around her however, and it was largely through their fundraising efforts and support that she was able to study with private teachers.

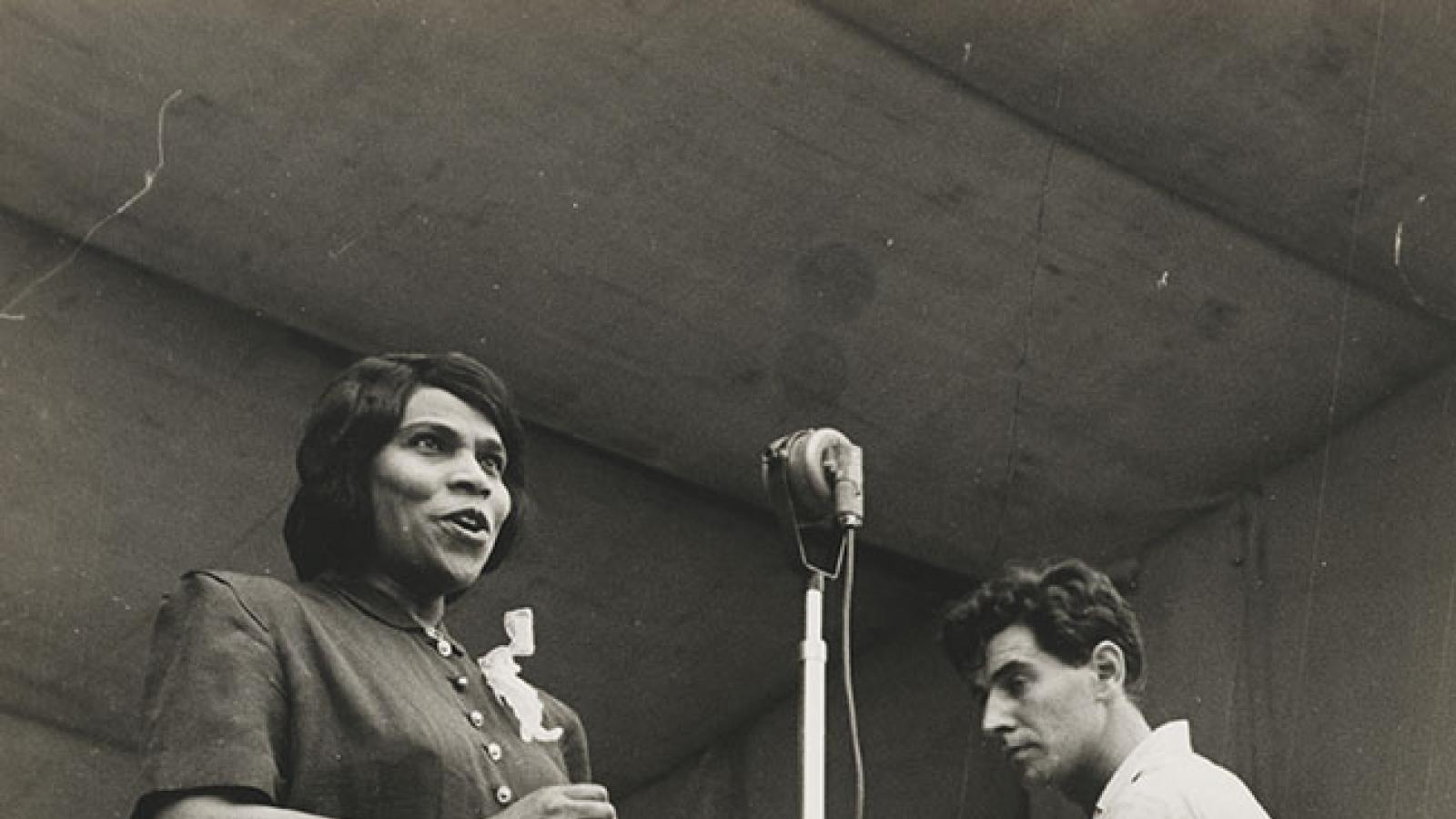

Anderson eventually moved to Europe in the late 1920s to more freely pursue music, as conservatories and concert halls there were not constrained by the same discrimination she faced at home. It was there that she more fully developed her technique and came into her own as an artist, paving the way for superstar status. Anderson had incredibly widespread appeal—her image was used to sell everything from cameras to tape recorders—and Ureña noted that a colleague at another institution referred to Anderson as “the Beyoncé of her day.” She cut an elegant, glamorous figure, and the magic of her voice (which can be heard through a series of videos at the exhibit), inspired other artists as well, including photographers Richard Avedon and Irving Penn.

Her role as artistic muse is perhaps most evident in the exhibit through a 1965 painting by Beauford Delaney, which depicts Anderson draped in a yellow dress against a yellow backdrop. She seems almost to glow with an angelic light, which Ureña said was indicative of Delaney’s longtime interest in Anderson.

Despite her celebrity as an artist, civil rights figure, and later, as a diplomat, Anderson shared a relatively quiet home life with her husband Orpheus Fisher at their farm in Connecticut. She took pleasure in photography, cooking, and sewing, and was in the habit of touring with her sewing machine.

If it seems charmingly modest for someone with such a remarkable life and career, it is. But modesty was Anderson’s natural tendency. At the end of the exhibit, there is a quote from a 1989 interview between Anderson and Brian Lanker, who photographed Anderson and other black women for his I Dream a World series. Anderson said:

“I don’t feel that I opened the door. I’ve never been a great mover and shaker of the earth. I think that those who came after me deserve a great deal of credit for what they have achieved. I don’t feel that I am responsible for any of it, because if they didn’t have it in them, they wouldn’t have been able to get it out.”