From the Archives: The Early Work of Photographer Gordon Parks

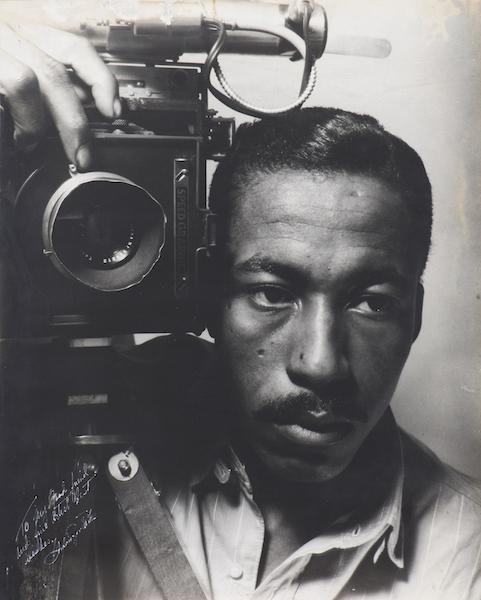

When 25-year-old Gordon Parks picked up his first camera around 1937, he had already survived a period of homelessness, tried his hand at composing music, and worked as a waiter on one of Northern Pacific Railway’s luxury trains. He was years away from being Life magazine’s first African-American photographer. He wasn’t yet a prominent voice in the struggle for Civil Rights. He hadn’t yet learned that the camera was going to be his “weapon of choice,” as he put it, the thousands of photographs he was yet to take indelibly illuminating the humanity of African Americans not yet 100 years removed from the ravages of slavery. Organized by the National Gallery of Art and the Gordon Parks Foundation, the traveling exhibit Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Work 1940-1950, sifted fact from fiction to present a portrait of the photographer as a young man on his way to becoming a revered artist the power of whose work continues to widely influence new generations, from artists to activists to every day people who continue to see themselves reflected in his work. We spoke with exhibit curator Phillip Brookman when the show was at the National Gallery of Art in early 2019 to find out the origins of the show and what it teaches us about how Gordon Parks the self-taught photographer became the legendary Gordon Parks we know of today.

NEA: What is the story you want to tell with this show?

PHILIP BROOKMAN: I wanted the exhibition really to be about how Gordon Parks becomes Gordon Parks. We know him as an extremely accomplished photojournalist and social documentary photographer working for Life magazine and doing stories about youth gangs and segregation and poverty and fashion the world over. But what we didn't really know is how he got to be who he became. What was it that inspired him and helped him and brought him to that point? [This exhibition] really tells about how Gordon Parks begins as a self-taught photographer, and there are a number of the very first photographs he took, in the exhibition. Then it shows how he gains both training and experience and takes advantage of his opportunities and works really, really hard to rise to the very top of his profession in the span of ten years, between 1940 and 1950.

NEA: What kind of research goes into putting together a show like this?

BROOKMAN: I had talked to [Gordon Parks] extensively about his life, and I'd ask him certain questions, but he didn't remember a lot of his early career. He embellished his stories. He did everything he could to create a sense of mythology around his work, primarily to use his own autobiography as a teaching tool, or as a story that would encourage young people to understand they could do anything they wanted with their lives.

I went back and I read through everything he had written, and then I began kind of piecing together a list of all the questions I had and the archives I might need to go to to really understand his beginnings. I went to the Chicago Public Library, for example, and began to consult the papers of people that he had known in Chicago when he worked there in 1941. I looked through many boxes of old papers, and in those materials I began to find some of Parks' early photographs that weren't known. He had talked a lot about how he had photographed on the streets of the Chicago, and it was such a transformational moment for him where he really moved from being a portrait photographer, self-taught, to being a social documentary photographer. No one had ever seen those pictures; they just were missing. I [had] asked him, "Where are your negatives? Where are those pictures?" And he kind of smiled and said, "You know, I threw them out. I didn't know what it was at the time." And I think that's partly true. I think he left a lot behind. So I started in Chicago looking for stuff.

NEA: Being already familiar with his work and knowing him personally, what surprised you the most as you were doing your research?

BROOKMAN: I was most surprised by the information that we found about Parks' early life, [about] his family—who they were, where they came from—and how he became a photographer. That was really the interesting part, because he has a very specific way of talking about that. One of the things I always questioned [was how he spoke] about coming to photography by seeing pictures in magazines that he found on a train when he worked as a waiter on the dining car on the Northern Pacific Railway. He describes specific pictures in his memoir, Choice of Weapons. These are photographs by Dorothea Lange, for example, and Arthur Rothstein, who were photographers for the Farm Security Administration, and they photographed the Dust Bowl, something Parks could really identify with himself. But in fact those pictures weren't published at the time in magazines, and so I had to go back and think about, "What was it he saw?" So I looked at old magazines in the archives of the Farm Security Administration, in the Roy Stryker papers, and every source I could think of.

It was really interesting to begin to think about that history and how that history impacted Parks, and what was it really that he was doing and how did he come to be a photographer. The really transitional moment for him in Chicago is when he applies for and receives a fellowship from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, which was a really significant philanthropic organization based in Chicago that funded in part fellowships for African-American artists to further their careers. I was able to consult extensively the archives of the Rosenwald Fund, and in there you find his original application, which contradicts his own story. He talks about how he applied for the Rosenbaum Fund Fellowship toward the end of 1941, and he receives the fellowship before Christmas, and he's in Washington just after New Year's. And he chose to come to Washington because he was inspired by the Farm Security Administration. In fact, he receives the fellowship in April of 1942, and that's documented in the whole application process, and he applied to photograph extensively throughout the sort of Midwest and Northeast, both to get training and also to picture "the American Negro" in all different aspects of their lives, not just the poverty but also the education and the improvements, and the segregated environment of the United States in 1942. So that's what he applied to do, and—from what I was able to glean from the archives and all the letters and everything—Parks was actually directed to the Farm Security Administration.

There's a close tie, I found, between the Farm Security Administration and the Rosenwald Fund, and in fact the U.S. government needed a photographer like Parks working in Washington in order to make pictures that would help to encourage African Americans to support the war effort. This is also the very early days of World War II. So all this history is wrapped up in his early career, and I think that it's just interesting to go back and really look closely at the social, political and cultural context of Parks' beginnings.

NEA: Would it be fair to say that some of that disparity between how Parks told his story and what actually happened was also part of what he was doing in his photographs, in showing African Americans as self-sufficient and capable and not needing that divine intervention, so to speak?

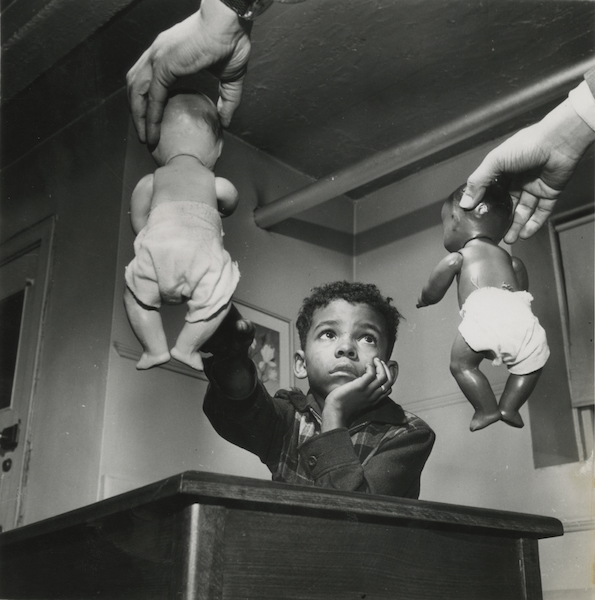

BROOKMAN: I think that's absolutely right. I think that Parks was interested in becoming a photographer who could redefine the image of African Americans in the United States in the very early days of the modern civil rights movement. That coincides with the beginning of World War II. So I think that his photographs and his aspirations then were very much about looking at all aspects of the culture. It's hard to say exactly today how much of this is Parks' original idea or how much of it comes out of his experiences. I think a lot of it comes from the training that he got early on. He was completely self-taught, and he wanted to be a musician, and then he discovers photography and he teaches himself photography, and most of what he did in his early career was portraits, because he could make money doing that. And then as he comes to Washington and gets his great apprenticeship with the Farm Security Administration photographers, it's then that he begins to think about and write about and understand how it is that he can portray the poverty and segregation and inequality that he himself had grown up with. That's really what he wanted to do, in addition to documenting the ways in which that was changing. In the early 1940s he begins to take control of the images that are made of African Americans, and shows the middle class and the upper class in Chicago, and documents that through portraiture and fashion pictures, understanding that all of those things are part of that culture, and an important part of it. But he also wanted to—as he said—use the camera as a weapon against the poverty and racism he had grown up with. And so he began to do both.

NEA: I was reading one of the opening essays in the catalog for this show, and it asks the question: "Should art about African-American life be created for its own sake, or is it inherently political?" How do you think Parks would he have answered that question?

BROOKMAN: I think that Gordon Parks understood from the beginning that all art is political, and he understood that through his associations with artists and writers and poets and sculptors, painters, all of the people working in and around Chicago during the late 1930s and early 1940s. Parks came to the South Side Community Art Center [in Chicago] in 1941 and he was given a darkroom and studio space there in exchange for him helping with the photography. The South Side Community Art Center was really a focus of extremely interesting and aspirational, high-quality art. It was a federally funded art center that had just opened its doors when Parks went there, and he was around artists like Charles White and Langston Hughes and Eldzier Cortor and Margaret Burroughs. All these young artists had really been thinking a lot about the relationship between their art and the politics of the time. They wanted to use their art as as a weapon to fight against what they saw in their neighborhood right around them. I think by the time Parks chose to be an artist himself, he knew that all art would be political, whether it's making pictures that redefine the image of the African-American middle class for all Americans, or whether it would be hard-hitting social documentary work.

NEA: I was really struck by how often Parks received direct as well as indirect funding support from the federal government, whether it was the fact that the South Side Art Center was supported with federal funds, or his work for the Farm Security Administration, and then the War Information Office. How do we think about that federal support as part of Parks story?

BROOKMAN: It's totally part of the story, and I actually thought about it a lot because I think that the government support of the arts in the 1930s and early 1940s was extremely important in redefining how the country thought about art at the time. So this is the Great Depression, and as part of Roosevelt's New Deal, agencies were formed to help artists, help employ people. [People were paid] to do conservation work, but also to make murals and do easel painting. The government through the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project opened art centers in communities like Harlem and the South Side of Chicago and Oklahoma City, really all around the country. That created training opportunities for people who were unemployed, but also it employed artists to teach in the art centers, and they became like community centers around the arts. This was a very, very carefully thought through idea at the time, and I think it was extremely successful, but also controversial, just like it is today. Gordon Parks comes into this with already an understanding of a photography program that was started within the Farm Security Administration, which was actually an agency [working to] resettle and retrain rural farmers who had lost their land, or couldn't farm their land, because of Dust Bowl conditions. They created within that [mission] a documentary photography and film unit to document the [agency's] work, and it turned out to be one of the great photography programs of the time and helped to redefine what documentary photography is. So Parks comes into this in its very final days, and so he's very, very involved in federally funded art programs, really, right from the beginning of his career as a photographer. As I said, he came to Washington through these ties between the Rosenwald Fund and the Farm Security Administration.

Parks came to Washington in May of 1942 with the idea that he would be a photographer who could make images to help the government ask African Americans to support the war effort, and it's the early days of the modern civil rights movement. The military is segregated; the defense industries are segregated; large parts of the country, including Washington, D.C., are segregated, through Jim Crow laws, and Parks is in the midst of all of this. I think that that kind of moment which he's thrown into really made him who he was. That's what this show is intended to discuss. I don't think that we've begun to find all the information yet.

I did a lot of research also in the National Archives and Records Administration, especially in the archives of the Office of War Information. So in 1942, the Farm Security Administration photographers begin to work for the government's war effort, and this is before the Office of War Information is even formed. By the time it's fully formed later in that year, the Farm Security Administration photographers actually moved to the Office of War Information. They were moved there because the FSA is really beginning to be dissolved. So the photographers begin to do work that is in support of the government's information programs around the war effort. At the same time, because the military and the defense industries and large parts of the country are still segregated, civil rights leaders begin to argue that this is an opportunity to begin to once again to question inequality in the U.S. For example, A. Philip Randolph begins to organize a march on Washington against the idea that the defense industries won't hire African Americans when that's needed. Black people are drafted into the military and end up in segregated units with jobs that aren't equal to others. Because of all this, it's a time when a lot of African Americans argue against supporting the war effort because of the inequality. Out of that develops really early civil rights arguments that go on to help desegregate the military and the defense industries. So Parks is in in the middle of all this [as a] photographer. [He takes photographs of] the Frederick Douglass dwellings, new segregated housing built by the government at Anacostia, D.C, and the Office of War Information uses his photographs in a pamphlet that they publish and distribute nationally, called Negroes in the War. It's this piece of propaganda to say to the African-American population in the U.S. that, "While things are not perfect, we need your support today, and if you support the war effort, then things will get better."

NEA: Do you think Parks struggled with that idea of his work being used as propaganda?

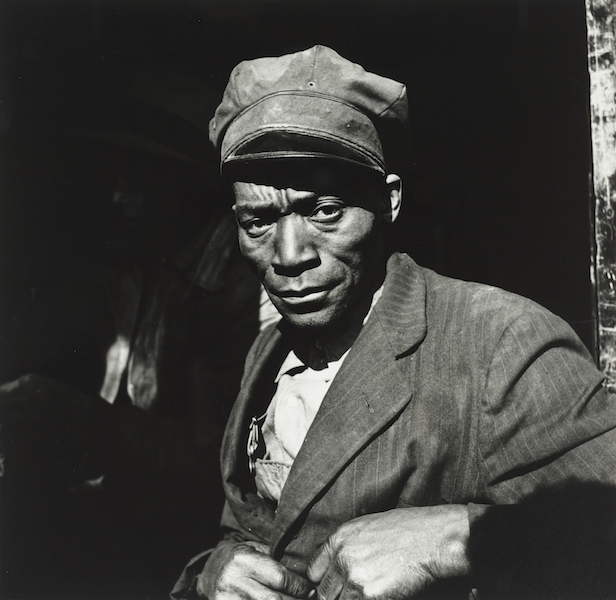

BROOKMAN: I think he must have been somewhat conflicted about it, because coming to Washington, he saw segregation all around him, experienced it himself. As a citizen, he did support the war because he felt it was not only his duty to do that, but he understood the consequences. His brother had been a lieutenant fighting in World War I in a segregated unit. I think that he found an opportunity to both work within the system but also work outside of it. He wanted to make those images that strongly represented his feeling about inequality. Unofficially, Parks was encouraged by his mentor at the Farm Security Administration, Roy Stryker, to begin making photographs of poverty and inequality in Washington. So he does that. He doesn't do it before he understands how to begin. He always said, "You can't just make a photograph of a bigot and label it, 'This is a bigot.' You have to make a picture that tells a story about how this comes to be, and who these people are and why."

NEA: One of the big surprises for me of the show was the series of photos of Ella Watson. I was very familiar with the solo picture of her with the flag—American Gothic—but I didn't realize there was a whole series.

BROOKMAN: So he meets [Ella Watson] the cleaning woman who worked at the Department of Agriculture in the building where the Farm Security Administration was based. When he met her and learned her story he then began thinking about how to make pictures that could actually not only document but tell about how this one woman lived in a world that was unequal during the war. He began to understand better how you could really use the camera as a weapon against inequality. He was trained by people who were storytellers, and they basically would make series of images that would document something through multiple images, like a movie would do. So when he met Ella Watson, he learned her story [as] somebody who had worked for the government for over 20 years but had been unable to advance in her job. So he worked with her to tell a larger story about who she was and why that was.

The one image of Ella Watson standing in front of the American flag became iconic because Parks used these symbols of the flag out of focus and the cleaning woman with her tools—a very upright, serious woman—to point out the irony of inequality. He photographed her at home and what her life was, that… she's caring for five people on her government salary. He begins to work with some of the very significant strategies that he learned at the Farm Security Administration, like using multiple layers, looking from the inside outside, looking through windows, all of those things; and he visited her church. She was a very religious woman who devoted also part of her salary to her church and also to buying war bonds to support the war. And so here was a woman who couldn't advance in this environment of racism and patriotism, and he told that whole story through a series of 80 photographs of Ella Watson and her family and her neighborhood that he makes.

NEA: What should visitors to the exhibit look for? What kinds of questions should they ask themselves as they're looking at the photographs? How do they have a conversation with the art?

BROOKMAN: I think that the exhibition is really accessible for all people. In some ways, my advice for all viewers is to really look closely at the pictures and try to see yourselves in them in some way. How does this work relate to the history of America, but also to you today? There's a lot of layers, the way the show is structured, but also there's a lot of text. So we tried to add a lot of information on the wall, both in labels and texts that go with individual pictures, to help explain what's going on and give the historical view. But also sometimes it's wonderful to know just who is that in the photograph and how did Parks come to make, for example, a photograph of the poet Langston Hughes. Who is that, and why is Parks making this photograph? It's a show I think it takes a long time to see, because there's a lot of pictures in the show, over 160 objects, but also there's a lot of text and information. You can also see how Parks' work was published in magazines and pamphlets and brochures. For example, we have a copy of "Negroes in the War," that Office of War Information pamphlet that used Parks' photographs. You can actually see that in the exhibition, and then understand how his photographs were used and why they were made, which I think is important. There's a lot of questions that somebody might ask about why are these good photographs, but I wouldn't worry so much about that. I would look closely at them and think about what they mean to you.

NEA: If there was only one thing I could write about this exhibit, about Gordon Parks, what would you want that to be?

BROOKMAN: I think what you can take away from this show is that anybody with an aspiration to do what they want can succeed. Parks was able to succeed against great odds to do what he wanted to do. He decided he wanted to be a photographer, but he had come from an environment that really limited his options. He never graduated from high school. He was never fully trained as a photographer, but he found ways to begin working and publish his work and then succeed at that profession. He was able to, I think, really take advantage of his opportunities, and by working really hard and studying what he was doing, he did succeed and really rose to the very top of his field. He also went on to become a filmmaker and in the late 1960s becomes the first African American to direct a major motion picture in Hollywood, which was based on his own childhood. It's called The Learning Tree. So he used his story then to inspire young people about how anybody can really succeed in what they want to do.