Art Talk with Curators Katie Delmez and Jamaal Sheats

Visual artist Terry Adkins had often noted that his artistic career really started in Nashville, Tennessee, specifically with his time at Fisk University, one of more than one hundred historically black colleges and universities (HCBUs) in the country. So while it might not be a surprise that Fisk collaborated with the Frist Art Museum in downtown Nashville to stage a two-location exhibition of Adkins’ work, Terry Adkins: Our Sons and Daughters Ever on the Altar, it might be surprising that this is the first major exhibition of his work in the city that had such an impact on him. The exhibition was supported by a National Endowment for the Arts grant.

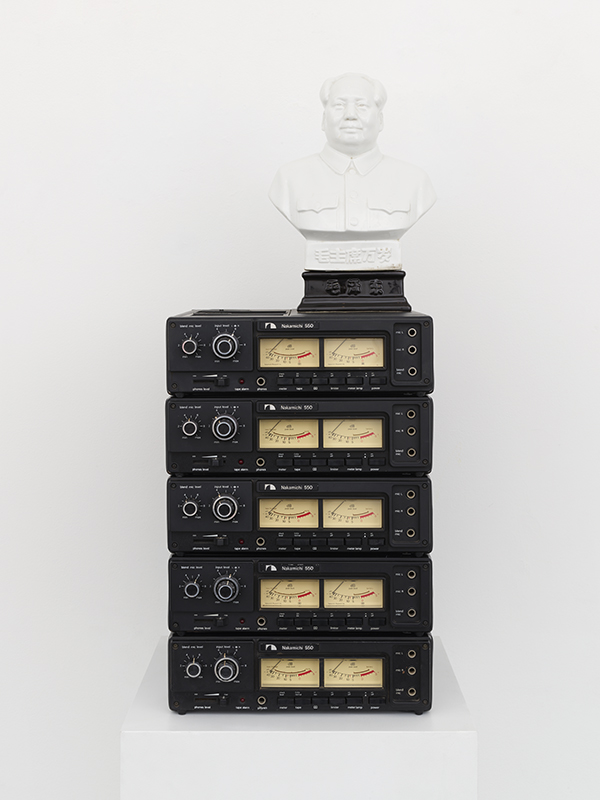

Adkins studied art at Fisk under David Driskell. He was also mentored by legendary Harlem Renaissance artist Aaron Douglas and studied sculpture with Martin Puryear and printmaking with Stephanie Pogue. He became an interdisciplinary artist, often incorporating music or instruments into pieces he called “recitals.” His work frequently featured specific areas of African-American history and little-known information about important African-American historic figures, such as George Washington Carver and W.E.B. Du Bois.

As Adkins’ first experience with art was when his father took him to a gallery at Fisk, it is only fitting that the university is participating in this exhibition of his work. We talked with the co-curators of the exhibition—Katie Delmez from the Frist and Jamaal Sheats, director and curator of the Fisk University Galleries—about the exhibition and the importance of shining a brighter light on the late artist’s work. The exhibition will run through May 31, 2020 at the Frist Art Museum and through September 12, 2020 at the Carl Van Vechten Gallery at Fisk University.

How the Collaboration Came About

Jamaal Sheats: Fisk is in North Nashville and Frist is in downtown Nashville, which is around maybe two miles away. We have partnered in the past, but not in this way. One day, Katie and I were having a conversation, and I said I would love to do a Terry Adkins show and Katie said she would too.

Katie Delmez: Terry himself had reached out to the Frist before he passed away about having an installation piece devoted to Bessie Smith shown at the Frist Art Museum. Bessie Smith was born in Chattanooga, about two hours away from Nashville, and Terry liked to have his work shown in an environment that had a connection with the subject. We were interested, but he did pass away unfortunately, and things were at a standstill.

As Jamaal said, we had this conversation, and it just seemed like a natural opportunity to partner, because Terry Adkins is such an internationally acclaimed artist—to be able to give him a bigger platform and more visibility in this city that he has these historic roots in, it just made so much sense.

You really have to see both exhibitions because he created such a range of subjects and materials that just one show doesn’t do him justice.

|

The Two Parts of the Exhibition

Sheats: The exhibition title derives from [Fisk’s] motto, and anybody who has spent quite a bit of time here at Fisk, it’s almost the spirit of Fisk that lives in all of us. When you think about Terry Adkins and his work as an artist and educator, he is Fisk.

The exhibition at Fisk certainly highlights his time here and the HCBU experience. You have two bodies of work that are directly relevant to W.E.B. Du Bois, who was a Fisk graduate, class of 1888. One is Darkwater Record and the other is The Philadelphia Negro Reconsidered, based on a study that DuBois did in 1896-97, the first sociological study on the black community. Adkins took that information, superimposed it, resized it, and created a body of work from it; it is a beautiful object but also an introduction to that study. [We are] an academic gallery, and students have responded to it in such a positive way.

You also have a body of work devoted to Matthew Henson, who traveled with Peary to the North Pole—whose image Adkins would have seen while a student at Fisk [a portrait of Henson by German illustrator Winold Reiss hangs in the university library]. But to know that he learned Inuit and learned the culture and the language, and that Adkins retraced his steps, that was also something the students were excited to learn more about.

There are works devoted to George Washington Carver, such as Progressive Nature Studies—everybody knows who George Washington Carver is but how many people really know he was an award-winning painter? This piece really brings that out.

Delmez: Terry Adkins was a trained musician, he played saxophone and guitar, and while he was at Fisk he was in the jazz orchestra. We are in the heart of downtown Music City, and we thought it would be appropriate to highlight that aspect of his career. As a musician, he would often incorporate sound files or actual musical instruments that he would repurpose into many of these bodies of works. These “recitals” would be devoted to musicians like Bessie Smith. We wanted to underscore that influence and part of his practice. At Frist, we have a portion of his recitals devoted to the great jazz saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker, and of course we ended up bringing the Bessie Smith piece here as he had hoped for so long ago. The third body of work is devoted to a period of Jimi Hendrix’s life that isn’t very well known. I think that is such a thread that you see through Adkins’ career, that he is either bringing visibility to people that he feels were underrecognized in their lifetimes or trying to bring attention to parts of well-known figures’ lives that most people don’t really know about.

In 1960, Jimi Hendrix came from the Northwest to Fort Campbell, where he trained to be part of the 101st Airborne. During that time, he did dozens of practice parachute jumps and he wrote about that experience in letters to his father. For Terry Adkins, who was very much inspired by Jimi Hendrix, he feels that was something that really shaped the later course of [Hendrix’s] music career, that it was something that stayed with him. Again, there’s the tie to the local—after he was honorably discharged, [Hendrix] came to Nashville and live here for a spell before his career really took off.

|

The Connection to Fisk and Nashville

Sheats: It’s really important that the exhibition is here in Nashville. This year, Terry would be celebrating the 45th anniversary of his graduation from Fisk, and I think it’s the perfect opportunity to welcome his work back home to Nashville and honor his legacy.

Delmez: And if you read any of the interviews he gave, or his writing, he always credited Fisk with being the first place of his visual arts practice. In fact, there was a traveling solo show of Aaron Douglas’ work, a retrospective, in 2006-7, and as part of a scholarly symposium that accompanied the exhibition, Terry Adkins did a performance piece as a way to conclude the symposium. That kind of shows the depth of his appreciation of his time and of the people he met in Nashville, at Fisk.

Jamaal and I have often commented on how rich and sophisticated and smart Terry’s work is. I think the audiences will respond well to it, but as a curator of his work, I’m learning more and more every time I see the pieces. I notice all these different aspects. We all can get a lot out of his work, and the response is going to be really engaged.