Arts in Corrections During the Time of COVID-19

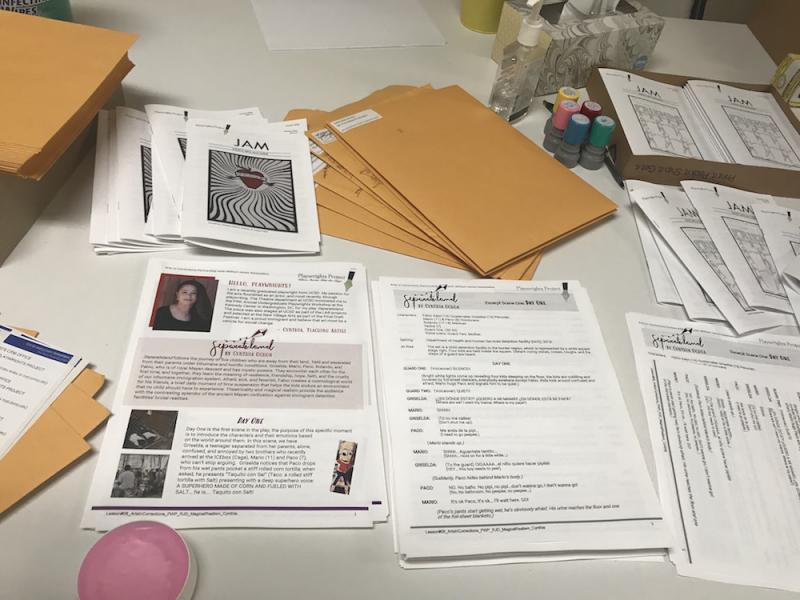

Lesson packets put together by Playwrights Project to reach incarcerated students while correcitonal facilities are under lockdown due to COVID-19.

In this blog series on how the arts are helping people who are isolated due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I have talked about how teaching artists are reaching patients and healthcare workers in hospitals, as well as older adults who are isolated in their homes or in residential care facilities. This final blog will look at a population that is often forgotten during times of crisis–people who are incarcerated in jails or prisons.

Arts programs in a range of disciplines, such as visual arts, dance, and theater, have taken place in prisons, jails, and juvenile detention facilities for decades. The work has been shown to create positive outcomes for not only the inmates but also staff and society as a whole. The effects are educational, behavioral, psychological, and vocational. The transformative effects of arts engagement on incarcerated individuals include improved emotional regulation, reduced anxiety and anger, better coping skills, improved social relations with other prisoners and corrections staff, more positive bonds with other prisoners, reduced disciplinary incidents, improved overall educational outcomes, and reduced recidivism. These programs also help prepare inmates to better function in society upon release.

Once the COVID-19 virus started to spread in March, students were cut off from arts in corrections programs around the country. Prisons and jails were locked down, restricting inmates to their cells or wards, and halting all family visits and programming from outside providers, including GED and higher education classes, recreation activities, counseling, and arts programming.

The result is that over two million incarcerated individuals have been left without important connection or engagement at a time when they are most vulnerable to the devastating effects of the pandemic. According to the Marshall Project, as of late October there have been over 161,000 cases of the virus among prison inmates across the country, which is a rate of over 5 times the general population, resulting in over 1,300 deaths. More than 36,000 staff, including corrections officers, wardens, nurses, chaplains, etc., have tested positive for the virus, and at least 92 have died. And the increased use of solitary confinement, the lack of contact with loved ones, and the cancelling of programming has had a dire effect on inmate mental health.

Teaching artists know how important arts engagement is for the emotional, mental, and educational well-being of their students and have been anxious to find ways to reach them during the lockdowns. In contrast to those in schools, hospitals, and nursing homes, most people in correctional facilities do not have access to computers or video instruction, so teaching artists face additional challenges in finding ways to reproduce the collaborative, cooperative classroom experiences that are the most transformative for their students. They have had to find a way to build trust with the students without the face-to-face interaction, while also making the remote learning engaging and fulfilling.

The National Endowment for the Arts has partnered with the Federal Bureau of Prisons to support artist in residence programs in a range of disciplines in federal prisons for over 30 years, and the teaching artists have had to make the transition to remote learning because of coronavirus restrictions. Since the late spring, for example, the creative writing instructors have created printed packets with lessons, guidance, and prompts, and have coordinated with prison staff to deliver and pick up the packets to review the students’ work and respond with comments. While writing programs are typically easier to conduct via correspondence than other art forms such as music or dance, correspondence courses lack the interactive discussions and sharing of work found in in-person creative writing classes, so the instructors have worked hard to create engaging and rich lessons for the students.

At the Federal Prison Camp Yankton in South Dakota, instructor Jim Reese, a faculty member at Mount Marty College, worked with prison staff to make the shift relatively quickly with his writing assignments and was even been able to produce the program’s annual anthology of writing and art, 4pm Count.

“Through everyone’s perseverance, 4 P.M. Count will publish its thirteenth consecutive annual perfect-bound book and it will be released by the end of the year. The staff of FPC Yankton has gone above and beyond to help maintain programming through alternative methods,” reported Reese.

State prison systems have also found ways to provide alternative programming during the COVID-19 lockdowns. California’s Arts in Corrections (AIC) program, run by the California Arts Council and funded by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, has continued to provide programming in 35 state prisons through its network of 21 arts organizations. One of these organizations is the William James Association (WJA), which partnered with Arts Endowment grantee California Lawyers for the Arts to fund arts programs in every state prison starting in 2013. The WJA worked with its 75 teaching artists to convert their classes in various art forms to paper lessons and help deliver the packets through the prison mail systems to students in 17 prisons across the state. These packets include warm-up exercises for writing or drawing, detailed instructions, writing prompts, art lessons, instructional illustrations, and, where allowed, supplies like pencils and paper. They also developed content to encourage and inspire their students, including writing or visual art by the teaching artists and stories of life happening outside the prison walls.

One of the WJA’s partner organizations is Arts Endowment grantee Playwrights Project in San Diego, which runs playwriting programs in two prisons in southern California. In their typical playwriting classes, students write one-act plays, which are then produced for the students by professional actors. To adapt to the COVID lockdowns, Playwrights Project created weekly packets that included lessons with writing prompts for monologues and scenes, using different themes and theatrical styles. The students completed and returned the assignments, the teaching artists provided feedback with the next packet of lessons, and then actors produced the plays via Zoom. In addition, the organization assembled and shared the students’ work in a zine format to foster sharing and collaboration.

One of the largest providers for the AIC program is the Alliance for California Traditional Arts (ACTA), also an Arts Endowment grantee. Artists lead classes in 18 state prisons in traditional art forms such as storytelling, singing, theater, Mexican son jarocho music, West African drumming, and Native American beadwork. Their classes help to build community and connection between students, provide healing from trauma, and foster restorative justice. After the COVID-lockdowns, ACTA needed to figure out how to teach traditional art forms typically taught through participatory, in-person oral traditions to students who have no access to instruments or audio-video equipment. ACTA hired education consultants to work closely with the teaching artists to find the best way to convey their specific cultural traditions and art forms via paper lessons. The result is a set of rich, colorful publications that convey the history and culture of the traditions, with lessons on creating music and rhythm, music theory, visual art exercises, and informative stories about the world outside the prison walls, designed to engage the students and help provide a bridge between the inside and outside world. They have also created over 30 instructional and informative videos designed to be broadcast throughout the prison closed circuit television (CCTV) systems.

While programs are finding some success, teaching artists are frustrated that they are not reaching nearly as many students as they normally reach. Prison staff have been under incredible stress and pressures in responding to the pandemic so they are limited in their ability to assist in distributing materials. In addition, student numbers are affected by prison transfers or early release, while some students simply cannot participate due to illness or other complicating factors from the pandemic.

Teaching artists, however, are finding that the students that do participate are incredibly appreciative and responsive to the lessons, which are providing some engagement and respite during a very stressful and isolating time. The teaching artists are also finding this period to be generative and productive, as they have had to be creative and flexible as they find ways to improve their delivery system. They are also being more collaborative with each other, building connections as they experiment and share ideas and solutions. The Justice Arts Coalition, a network of artists and arts programs throughout the U.S., has held weekly Zoom calls since March to provide a much-needed support system for teaching artists, who use the calls to share their challenges and successes, as well as their best practices and curriculum.

As the pandemic has continued, some teaching artists have also gained access to technology to reach their students. The Yankton Federal Prison Camp program, for example, recently began using WebEx video conferencing software to provide remote learning. Instructor Reese and his students are excited to be able to once again see each other and engage in group writing projects.

While it’s unclear when teaching artists will once again be able to work directly with incarcerated students, during the COVID-19 lockdowns, arts program staff have worked tirelessly to support the shift to distance learning and alternative programming. Teaching artists have remained committed to creating meaningful, rich, and engaging lessons that help their students grow, heal, and find peace during an extremely stressful and isolating time. These dedicated arts workers are eager to get back into the classroom, but they will continue to do the work, packet by packet, to provide a lifeline to this vulnerable population that counts on them.

Beth Bienvenu is the National Endowment for the Arts Director of Accessibility.