Hispanic Heritage Flashback Friday: Sandra Cisneros on Recognizing Ourselves

Sandra Cisneros. Photo by Alan Goldfarb

As a child, Sandra Cisneros read voraciously, taking in “the language of books and writing and magic and mystery.” It was only much later, while attending the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, that Cisneros realized that her own language of working-class Mexican Americans was nowhere to be found within literature.

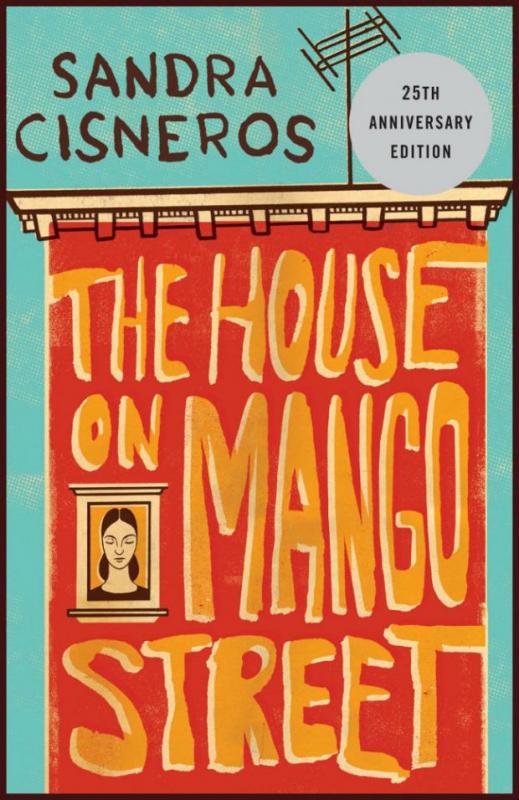

This changed in 1984 when Cisneros published The House on Mango Street. A coming-of-age story composed of some four-dozen vignettes, the book reveals both the poetry and hardship of Cisneros’s own upbringing. It has since become a perennial favorite for high school reading lists, expressing the voice of young Latinas while serving as many students’ first glimpse into an American story that might not be their own. The two-time recipient of National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowships and National Medal of Arts honoree discusses her seminal work, and her own coming-of-age as a writer.

HOUSES AND PAJAMAS

I think there’s a kind of lie that our education teaches us—boot straps and hard work, the American Dream. And you swallow it.

You could go around oblivious to it for a long time, 21 years in my case, until you go to Iowa and you realize what a privilege it is to be in that writing program. For me, it was a moment of houses, and reading about Nabokov’s house that he left behind in Russia, and Baroness Blixen’s house in Africa when she had a coffee plantation. All of these books were written from a perspective of people who owned their own houses and lived in houses that by my standards were roomy, comforting, and safe, and something one dreamt about with longing and loving memories. I didn’t have those kinds of images in my life.

The moment that I discovered my voice was also the moment I discovered class difference. I was in a seminar on memory and imagination. You know that dream you have that you go to school and you’re wearing your pajamas? It was that moment I suddenly realized, “Oh my God, I’m in my class here and I’m wearing my pajamas.” It was that horrible feeling of embarrassment that I realized I didn’t have a house. I felt naked. It had taken me 21 years to figure out I had been in my pajamas and no one—out of politeness or generosity or cruelty—had ever told me.

WRITING THE HOUSE ON MANGO STREET

The first impulse when I realized I was wearing my pajamas was, “I don’t belong in this club.” My first reaction was to go home and lock myself in my bedroom for the weekend and consider coming home and quitting the program.

But Mexican women are very strong women, and the opposite side of sadness is rage. It took me only a weekend to get to the opposite side of my sadness. Why had I never seen literature written about my community with love and honesty? Why have I never seen my house in newspapers or magazines or in ads or cinema? It’s never been portrayed. My community has never been portrayed with honesty. So I got angry. This is a wonderful thing you can do with rage if you know how to transform it: You can either light up Las Vegas, or you can create a Chernobyl. I had been wanting to create Chernobyl all weekend. Then I realized I’m going to stay here and write that book I haven’t seen. I wrote The House on Mango Street on the side for no credit, while I was in poetry workshop, to keep my spirit alive.

STORIES OF THE HELPLESS

When I wrote Mango Street, in the beginning it was as a memoir with the intent of writing something that was just mine, that no one could tell me was wrong. That’s how it began.

By the time I finished it, I was working in a school in a Latino community in Chicago—a very poor, alternative high school. I started writing stories of my students’ lives and weaving it into this neighborhood from my past.

During that period, when I had my face in the dust and didn’t know what to do in this 50-student school with no money and minimum wage—chalk I had to bring to class, girls and boys whose lives were so difficult, lives that no head of state could ever imagine—I was really frustrated as a high school teacher as to how to save their lives. The only thing I could do was to write about them and try to find some consolation before sleeping. These stories were written from that very helpless state. I think when we’re most face-in-the-dust impotent, and we put ourselves at service to others, that’s when we really are channeled to light. I think that’s why the book is a success. I wasn’t thinking of the reader, or that the book is going to be published. None of that. I think the less you can think about the reader, and the more you work on behalf of others, I really believe that it puts you in a state of grace.

WRITING FOR A HIGHER PURPOSE

My whole life is a mission. Every time I pick up the pen it’s in service, and I do a meditation so that I can be of service. I’m very lucky in this way; I see my work as work of the spirit. I cannot disconnect creative writing from spiritual work, just like someone being in a monastery or meditation sangha. It’s all the same to me.

We’re living in such horrible times for people of color, immigrants, working-class people. There’s such open vilification of things I never would have imagined I would hear in my lifetime. I feel as a writer that I have a gift of expressing things that people feel, and speaking for them, and also creating clarity and bridges between communities that misunderstand one another. You can’t see clearly in times of fear. So I try to be of some use because when you witness or read intense hatred, it’s your obligation to try to right the planet. Otherwise, you’re part of the problem.

[In my work,] I hope that people see their story being written about, and it gives them new options and possibilities to imagine something outside of what television or what the school counselor could imagine for them. I get lots of letters from all kinds of people. There are some people most unlike me, maybe a white male, who’s riding the subway and said he read my book and it made him look at people on the subway across from him in a different way, in a more human way. I really hope it will humanize [us] to be more compassionate, to recognize ourselves. If you can recognize yourself in the person most unlike you in literature, then the book will have done its work.

This interview was originally published in the 2016 NEA Arts issue Telling All Our Stories: Arts and Diversity.