Spontaneous Magic: Celebrating Roots Music with the Arhoolie Foundation

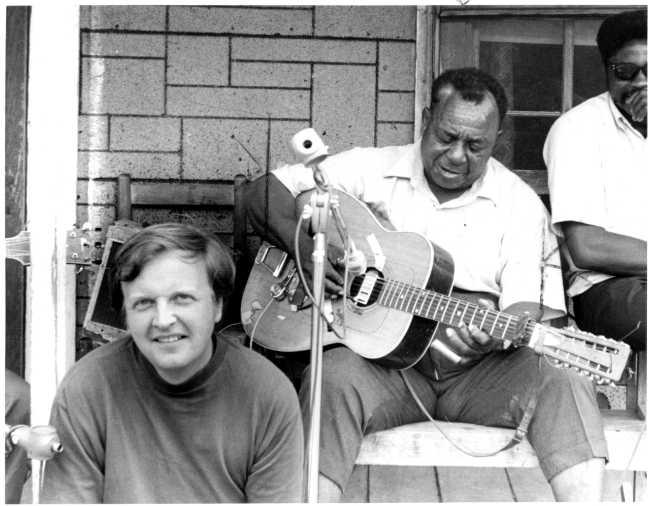

When Chris Strachwitz founded Arhoolie Records in 1960, it was clear that he had a different approach than most record producers. Rather than bring musicians into a studio and finesse songs to sonic perfection, he traveled the country seeking out the very best regional musicians he could find, from Mance Lipscomb and Lightnin’ Hopkins to Los Pinguinos del Norte, and if possible, recorded them on the spot. He wanted to capture the kind of spontaneous magic he heard when they played in small venues for audiences, which Strachwitz felt helped breathe energy into the performances. The first take was typically the only one he wanted.

“He likes to think of himself as a song catcher,” said Adam Machado, executive director of the Arhoolie Foundation, which documents, preserves, and raises awareness about roots music, and which recently received a National Endowment for the Arts grant. “It's a snapshot, he likes to say, of a moment. It's never going to be the same again. That's where the catching comes in—you’ve got to catch it where it is, as it is, when it is.”

Arhoolie Records, which was acquired by Smithsonian Folkways in 2016, went on to become one of the most celebrated labels in roots music, and is responsible for helping musical styles like zydeco, Cajun, and Tejano reach ears and gain relevance across the country. In 2000, Strachwitz received the inaugural Bess Lomax Hawes National Heritage Fellowship.

“Just as he was introducing outside audiences to different styles of regional music, he was also reflecting it back to the communities it came from,” said Machado. “His reissues of older recordings from 78s were especially important in this regard. It was a time when you didn’t have everything at your fingertips. In 1960, you couldn’t just open up your Spotify app and hear any kind of music from any place or any period you wanted. It was hard to get your hands on this stuff, even when it came from your own backyard.”

At the same time that Strachwitz was producing records, he was also collecting them, sometimes purchasing entire warehouses full of recordings. The Arhoolie Foundation was originally founded 25 years ago to preserve the label’s Frontera Collection, which is the world’s largest known collection of Mexican and Mexican American commercial recordings.

Machado said it was the late UCLA professor Guillermo Hernandez who convinced Strachwitz that the collection, which Strachwitz amassed throughout the course of his collecting career, was “a cultural treasure that needs to be preserved and shared with the world. He helped Chris realize the value of what he had: not simply a collection of records, but a huge gathering of stories told in songs documenting all aspects of the Mexican American experience.”

Eventually, the foundation moved to digitizing additional collections donated by Strachwitz and others, giving audiences around the world free, instant access to a treasure trove of musical artifacts that celebrate and introduce us to diverse communities around the country.

With a new, highly searchable website, it’s become easier than ever to access the Arhoolie Foundation’s holdings. With their latest grant from the Arts Endowment, the foundation will continue to create curated online access to its vast collection of music, photographs, interviews, films, videos, posters, and assorted papers. They are also planning physical exhibitions, including a traveling exhibit that will bring highlights from the Frontera Collection to Mexican American communities across California.

These digital and physical offerings are not only a celebration of the sounds of roots music itself, but provide entry into the cultures that have shaped them, practiced them, and passed them on. As Machado noted, regional music is inextricably tied to the people who create it, from their beliefs and histories to the food they eat, the work they do, and the weather outside their door.

For those from a particular community, listening to music of that community can be a homecoming of sorts, serving as an aural link to familiar ways of life, and as a point of connection with their heritage. Machado said that while the Frontera Collection’s YouTube Channel now hosts 50,000 recordings, and has generated nearly 8.5 million views since its launch in February 2018, that’s not necessarily how he measures the foundation’s impact. He explained, “More eye-catching than the raw numbers are the beautiful messages pouring in from people saying, ‘I grew up listening to this music at home; thank you for making it available to me again,’ and 'We knew our grandfather made records but we never thought we would have an opportunity to hear them.’”

Discovering Arhoolie can be just as meaningful for those who might be approaching a certain musical genre as a stranger. As outsiders listening to the music of a particular place, we’re given an intimate invitation into another culture, which can bring a new sense of appreciation for a community different from our own, and illuminate our shared humanity.

Machado quoted the late Texas folklorist Mack McCormick: “In a crowd of 2 billion people mashing together, there is increasing reason to value whatever introduces a sense of kinship among strangers.”

“Mack wrote that in 1964,” Machado added. “Today there are 7 or 8 billion people mashing together, and we don’t always play nice. Music is one way we can help to develop and nurture that sense of kinship, and maybe even a little kindness.”