An Appreciation of Stephen Sondheim

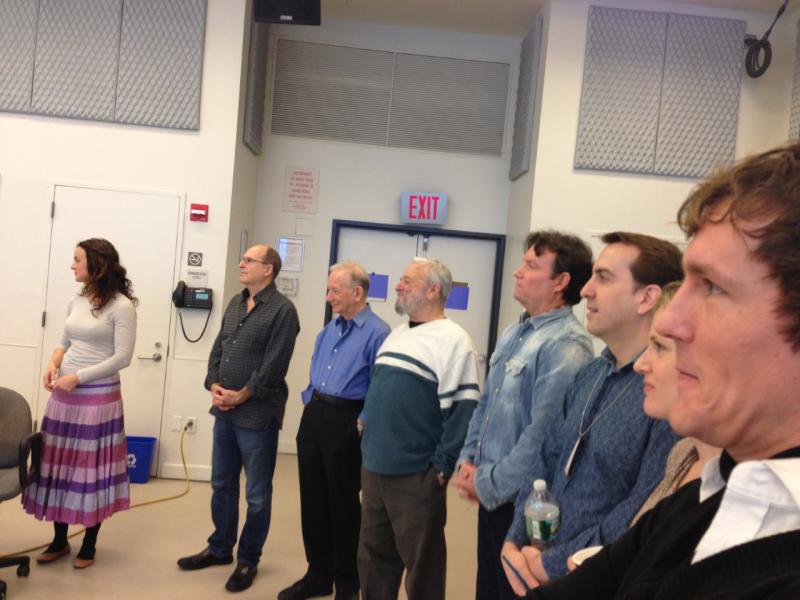

During the Classic Stage Company’s production of his musical Passions, Stephen Sondheim (middle) takes in the first rehearsal. Photo by Greg Reiner

This weekend, we lost a legend in musical theater, Stephen Sondheim. With a career spanning from the golden age of American musicals dominated by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein (Sondheim’s mentor) to 2021, when he was working until his last moments on a new musical, the musical theater field will forever be defined now as Before Sondheim and After Sondheim.

My relationship with Stephen Sondheim dates back to long before I ever met the man in person. Like so many of my generation, the PBS broadcast of Into the Woods was my gateway into Sondheim, followed by my high school’s production (with me as the Wolf/Cinderella’s Prince). From there it was a short ride to discovering Sweeney Todd and the rest of his works, leading to a deep dive in college with my thesis project of directing his Assassins. My first window to the kind of human Sondheim was came in high school when my classmate Gabe Lopez (Rapunzel’s Prince in our production), an aspiring songwriter at the time (now successful in his own right), wrote to him for advice, and received back in the mail a hand-typed note of encouragement, which led to a continued correspondence over the years. In the wake of his passing, one of the most heartwarming things to come out is the volume of people who have shared their own letters from Sondheim, revealing an astounding generosity of spirit that has doubtless resulted in countless ripples throughout the musical theater field. As he wrote in Pacific Overtures:

It’s the ripple, not the sea,

Not the building, but the beam,

Not the garden, but the stone.

When I was executive director of Classic Stage Company, an Off-Broadway theater in New York City, we put on a production of his musical Passion. I have so many memories of this time, and my own interactions with the master, which were inspiring, prickly, but always more generous than they needed to be. I took it upon myself to make sure he had his preferred beverage at the time (white wine, lots of ice) in hand as he entered the theater, and I would then often linger in the theater vestibule to witness his sheer joy watching the brilliant cast bring life to his words and music. Every time he attended, he made it a point to stay after the show to go backstage and thank the cast for being his collaborators. And his generosity towards his collaborators didn’t stop at actors—he was evangelical about crediting his orchestrators (the great Jonathan Tunick in our case) and book writers, making sure to credit and include James Lapine in every discussion of Passion. But the moment in the process that I think captures him perfectly, was during the sitzprobe (seated rehearsal), when he paused the orchestra running through a moment of music to single out a single note being played by the clarinet at one point. He changed it on the spot, dictating that it should be played a tone lower. I thought of that precision when I read his advice to young songwriters:

Content dictates form.

Less is more.

God is in the details.

There’s often conjecture about whether Shakespeare wrote all of the plays credited to him, if one man could really encapsulate that vast array of humanity and genre that he did. But, as Lin-Manuel Miranda noted after Sondheim's passing, we are all privileged to have been alive at the same time as Stephen Sondheim, so we know that he alone wrote all of the music and lyrics in his name. To think that one mind can contain such multitudes, from Sweeney Todd to Desiree Armfeldt, from Leon Czolgosz to Fosca, is astounding. To think that a human mind can come up with a lyric like “It’s a very short road from the pinch and the punch to the paunch and the pouch and the pension” and also think to rhyme “personable” with “coercin’ a bull” is beyond the comprehension of my own mind. And those are just two examples of thousands. And yet, to understand that all of this did come from one person gives us hope for the boundless imagination of the human mind, of our shared humanity, of our capacity to understand each other and grow towards a better future.

Greg Reiner is the Theater/Musical Theater Director at the National Endowment for the Arts.