New Grant Spotlight: On Site

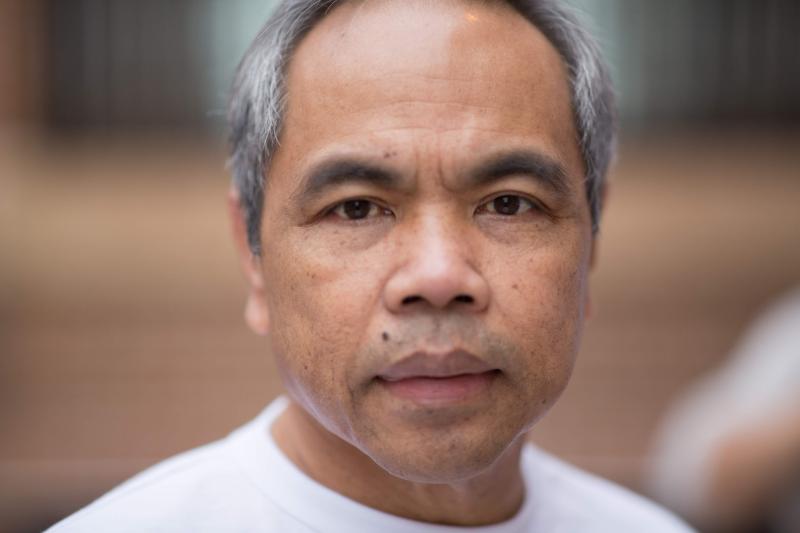

Portrait of Sarith Peou. Image courtesy of the Weisman Art Museum and We Are All Criminals.

Sarith Peou, an incarcerated artist at Stillwater Prison in Bayport, Minnesota, was in the midst of a collaboration with artist Carl Flink when he contracted COVID-19 last year.

“At one point, I gave up hope that our work would ever see the daylight,” Peou told the National Endowment for the Arts via email.

Peou and Flink’s already limited communications were disrupted by prison lockdowns caused by outbreaks. According to Marshall Project data, Peou’s case is one of 397,422 COVID-19 cases reported among incarcerated people since mass testing in prisons began.

Peou didn’t know that while he was sick, trapped in his cell, Flink continued to work hard on their piece. In November 2020, a correctional officer informed Peou that he had seen a video Flink made about their collaboration on social media.

“I broke down in sobs,” Peou said. “I felt seen.”

Peou and Flink’s collaboration was part of SEEN, a poetry and portrait project from criminal justice nonprofits We Are All Criminals (WAAC) and the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop (MPWW). Peou and Flink will continue to collaborate this year on a new project, On Site, which grew out of SEEN and is supported in part by a $40,000 Arts Endowment grant.

The Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum (WAM) at the University of Minnesota is also a partner in the two-year project that will support the development and presentation of original artworks created jointly by Twin Cities artists and incarcerated artists at Stillwater Prison.

The first year of the project will focus on building the relationships between artists on the “inside” and artists on the “outside,” experimenting with materials, and designing the artworks. All artists and collaborators will be compensated for their participation in the project.

Boris Oicherman, a curator at WAM and project director for On Site, said the project is not intended to serve as a rehabilitation or therapeutic tool for the incarcerated artists. Rather it is meant to acknowledge the contributions of incarcerated artists to Minnesota’s creative landscape.

“When I learned about [SEEN], the question I asked myself was, ‘Can a museum do something to support production of new work by those artists?’” Oicherman said.

“Museums serve many functions and one of those functions that is very often undervalued or underplayed is the support infrastructure for artists,” he added. He said it is particularly important to commission works by artists who have traditionally been excluded from museum exhibitions, such as incarcerated artists.

Portrait of B. Image courtesy of the Weisman Art Museum and We Are All Criminals.

B*, an incarcerated artist at Stillwater Prison, is another project participant. He said the voices of incarcerated artists deserve to be elevated just as any other artist’s would.

“If art's purpose is to express, define, explore, question, subvert, create awareness, and be the ultimate medium to influence meaningful dialogue, then incarcerated artists are ultimately and inherently part of the art community choir,” he said. “We are representatives of our space and time, like every artist throughout history.”

Emily Baxter, WAAC’s founder and executive director, has spent years developing relationships with the incarcerated artists participating in On Site through her work as a criminal justice activist. She described her responsibility as the project’s curator as catalyzing connection.

“Incarceration frustrates many things—including communication. During the development stage of the partnerships, my role, more than anything, is to act as a conduit for conversation and collaborations,” she said.

Peou noted that incarcerated people are wary of being used, especially as they are often deprived of information, so ongoing communication and developing trust is essential during a project like On Site.

“Trust through storytelling and story listening,” he advised. “Try also to listen to what we don't say. We don't want sympathy if we could have empathy.”

B’s guidance for working with incarcerated artists echoed Peou’s.

“The first advice I would offer organizations working with incarcerated artists is to abolish the identifier ‘incarcerated’ from their conscious,” he said. “Allow yourself to be surprised and moved by the artists you work with, those human beings with certain life experiences that inform their unique voices.”

B adds that while there are obstacles when working with the Department of Corrections, that should never be a deterrent to working with incarcerated artists.

“Circumstance is the only aspect differentiating incarcerated artists from public artists, but we are still part of the greater shared community,” he said.

Portrait of Von. Image courtesy of the Weisman Art Museum and We Are All Criminals.

On Site will culminate with an exhibition at WAM, which will be accompanied by a publication and programming. Programming will include workshops, discussions, open studios, and educational programs as a way to encourage departments and community members across the University of Minnesota to connect.

Von*, another participating incarcerated artist, also noted the importance of community to this project.

“Our communities are damaged in so many ways, be it by someone else's hands, our own hands, or by our own distorted thinking,” he said. “A good place to start [healing] is to change how we view each other.”

Portrait of Jeff. Image courtesy of the Weisman Art Museum and We Are All Criminals.

Participating incarcerated artist Jeff* shared that making space for the person behind the art leads to healing.

“It helps society acknowledge our humanity, which leads to them seeing our value and potential, creating space for it, and investing in it,” he said. “An incarcerated artist’s voice has the ability to contribute to healing in the community they once harmed.”

B said he hoped the project also contributes to renewed dialogue around criminal justice, not only for those participating in the project, but everyone affected by mass incarceration.

“For me, this project is an opportunity to be heard and seen, not as an individual necessarily, but as one of two million incarcerated people in this country who need a bit of humanity in their lives.”

*To protect their privacy, some of the incarcerated artists that participated in this interview used their first names or pseudonyms.