The Oldest Living Things On Earth: A Conversation with Photographer Rachel Sussman

What can a simple, unadorned photograph of a tree teach people about a heady concept like "deep time" or "year zero?" Quite a lot, actually, if the photographer in question is Rachel Sussman . She describes her own work as equal parts art, science and philosophy. The first two interests developed during her childhood. "I'd take my mother's 110 camera and take photos of trees during thunderstorms," she remembered. An undergraduate interest in philosophy added another dimension to her interests. "I became interested in ideas around deep time and perception, and also where the science and philosophical thinking starts to slip."

Sussman's art practice really came into focus, however, after a serendipitous moment during a trip to Japan. Days away from deciding to fly home early, she found herself on a remote Japanese island, photographing a 7,000-year-old tree. About a year later, Sussman launched the Oldest Living Things in the World project, a series that has since taken her all over the world to photograph everything from 3,000-year-old lichen to a 9,550-year-old spruce to an 80,000-year-old colony of aspen trees.

Though Sussman identifies as an artist, she's also had to earn her scientific bonafides along the way. As she explained, "There isn't an area in the sciences that deals specifically with longevity across species, because that would be too broad." So Sussman has become the expert through scholarly research, conversations with scientists, a great deal of detective work and determination. Ultimately, Sussman's work has not only given ordinary people a way to understand ideas around deep time, but it's also been a portal for connecting scientists, providing them with a platform to consider the intersections between their various specialties.

Sussman has exhibited widely in solo and group shows at venues including the Berlin Botanical Museum, the Montalvo Arts Center, the Museum of Contemporary Photography, the American Museum of Natural History and the Pioneer Works Center for Art and Innovation. The University of Chicago Press has also published a collection of her work in the monograph The Oldest Living Things in the World.

NEA: The phrase "deep time" comes up quite a bit in your work. Can you explain how that's different from regular time?

RACHEL SUSSMAN: The tricky thing about deep time is, different people will give you different definitions of it. One way I like to think about it is as a time scale that is just outside of our normal human experience. Sometimes, people refer to geologic time. If you think about the amount of time it took for the continents to break apart, that's geologic time. It's on this scale that's so much deeper than a human life span, so much longer than a human life span. One example I like to give from the Oldest Living Things series is the example of the map lichens in Greenland. They grow one centimeter every 100 years. And I love that statistic, in part because it's just mind-boggling in and of itself. But if you think about a human life span, we can wrap our heads around the idea of 100 years, but beyond that, we start to get fuzzy. Think about a time span of 500 years, 1,000 years or my minimum age for this project: 2,000 years. Then, that ties into this idea of year zero. For me, that's the important marker of deep time—in this case, because I really am trying to draw a parallel between human timekeeping and human culture versus the actual, enormous, expansive time that life has existed on Earth, or how long has Earth existed in the solar system. And how long has the solar system and the universe itself existed?

What I'm hoping to do is use this idea of deep time to connect with these time scales through these living organisms in a way that we can have some personal connection to them, to understand them in a living, organic way, as opposed to through complete abstraction.

NEA: And when you talk about the idea of year zero, what does that mean?

SUSSMAN: In essence, I'm asking, why is it 2014 right now? And this is something I address briefly in the Oldest Living Things book—how religion has played a huge part in deciding what year it was. But my point is more in general—that it's fascinating that we all got together and could agree what year it was, because it really is such an abstraction. In reality, isn't it more like "Happy 4,500,002,014?" So it's sort of saying, "Wait a second, guys—2014 doesn't mean anything." It's completely detached from the deep history or big history—as sometimes people refer to it—of our planet.

NEA: How did these ideas lead to the Oldest Living Things in the World project?

SUSSMAN: I had both a metaphorical and a literal journey, which brought me to the idea for the project. The literal journey was this trip to Japan that I took 10 years ago. It was 2004.... I had just finished an artist's residency at Cooper Union, and I had a new camera. I was making landscapes about the relationship between humanity and nature at that point, and they really were about philosophy, too.… When you’re traveling you have these expectations of what a place is going to be like before you get there. In Kyoto,[Japan], you think of all of these old temples. But I pull in on the train station, and there's Starbucks and Kinkos, and I'm like, "Oh, this just isn't what I thought it was going to be." I thought, "Maybe I should just go home," which is very unlike me. But then something gave me pause, which is that several different people had told me about this tree. It's called Jōmon Sugi. It lives on this remote island. They said, "If you're interested in nature, you have to go visit this

tree. It's 7,000 years old." And I was intrigued. And so I had one of those moments where I gave myself permission to go home, but then just turned around and went in the opposite direction.

It was no small undertaking to get to this tree. First, I had to get to the southernmost point of Kyushu [an island of Japan], so I took the train down there. And then, it was a three- or four-hour ferry ride to get to the island of Yakushima. And then, it's a two-day hike to get to the tree. So I was really committed. It ended up being one of the most rewarding travel experiences I'd ever had, in part because I got befriended by this couple on the ferry ride over, and by the time I reached the other side, I was living at a Japanese family's house for a week. It was amazing, and they guided me to the tree. People want to hear the story of, "Oh, I saw this tree, and then I got the idea," but that's not actually what happened. Obviously, this experience and seeing the tree had a profound effect on me, but it was over a year later that I got the actual idea for the Oldest Living Things. I think it took all of that extra additional time percolating because I needed to think through all of these disparate components. And I was sitting in a Thai restaurant in SoHo, having some dinner with some friends, telling them this story that I just told you. And then, that's when I got the idea. So I had my lightbulb moment, but the idea was probably a couple of years in the making, considering the time both before and after the trip.

NEA: How long has the project been going on?

SUSSMAN: Basically, phase one was 10 years—2004 to 2014. And it is ongoing. I have rather blithely said phase one is 10 years, and phase two is the rest of my life, but I don't know how that's going to play out. I mean, in part it's just not all that feasible for me to continue in the same way that I have been. I've gone into a lot of personal debt. And this isn't a funded academic project; it's a personal one. But even in my book, I mention that there are a number of organisms that I know about that I haven't visited yet, and there are even more on that list since the time the book came out. So I’d certainly like to continue to visit more of these old things. But I'd like to expand the project and open it up and allow more people to be involved in it in some way, and I haven't figured out what that looks like yet.

NEA: We see the work, and it's breathtaking. But I don't think we really ever think about everything it takes to make this work.

SUSSMAN: There's a tremendous amount of research involved, and most of the time is spent preparing. To really get down to the basics, it wasn't like there was an existing list of old things to photograph. This is an interesting art and science issue; there isn't an area in the sciences that deals specifically with longevity across species because that would be too broad. At first, I thought I would find an evolutionary biologist who would partner with me through the whole project. And everyone I spoke to said, "Oh no, we're not qualified." And I thought, "Wow, how can I be more qualified than you are?" I just had to make myself be the most qualified. So that meant doing an enormous amount of research and then usually tracking down published scientific papers whenever possible, and then tracking down whoever wrote them and hoping they're still doing active research. Oftentimes, I would meet with researchers while they were doing their fieldwork. That was the best-case scenario. Although sometimes I would just get a set of directions if nobody could meet me—like, "Here's a map," or "Here's some GPS coordinates; hope you find it," which I did.

NEA: Can you also say something about the equipment you used?

SUSSMAN: That camera that I mentioned I had gotten in 2004 is a Mamiya 7 II. It's a 6x7 medium-format film camera. It has been with me through the entire project and has been to every continent. Most of the work is shot on that, but when I was shooting underwater, I

used a digital camera in an underwater housing, and the only other thing that's digital is the digital optical microscopy. When I made images of the Siberian actinobacteria, that's a digital image made on a microscope.

NEA: What, particularly with this project, is the question that you think you're answering, or the story that you're telling?

SUSSMAN: Well, it's definitely layered. I'd say there's not one story: there are layers and layers of stories. And there are different ways that different people will enter into it. As an individual in the audience, you're going to bring a different set of experiences, whether that's "I live in or have been to Namibia, so I'm familiar with the Welwitschia plant," or the Welwitschia is something you've never seen before and it's this wild-looking thing in a harsh desert, and that's expanded your experience of what it can mean to endure.

But there are a number of themes throughout the project. One is obviously about the environment—sustainability in a way that I hope doesn't hit people over the head. It's not yelling at you; it's just allowing you to observe something differently and put the pieces

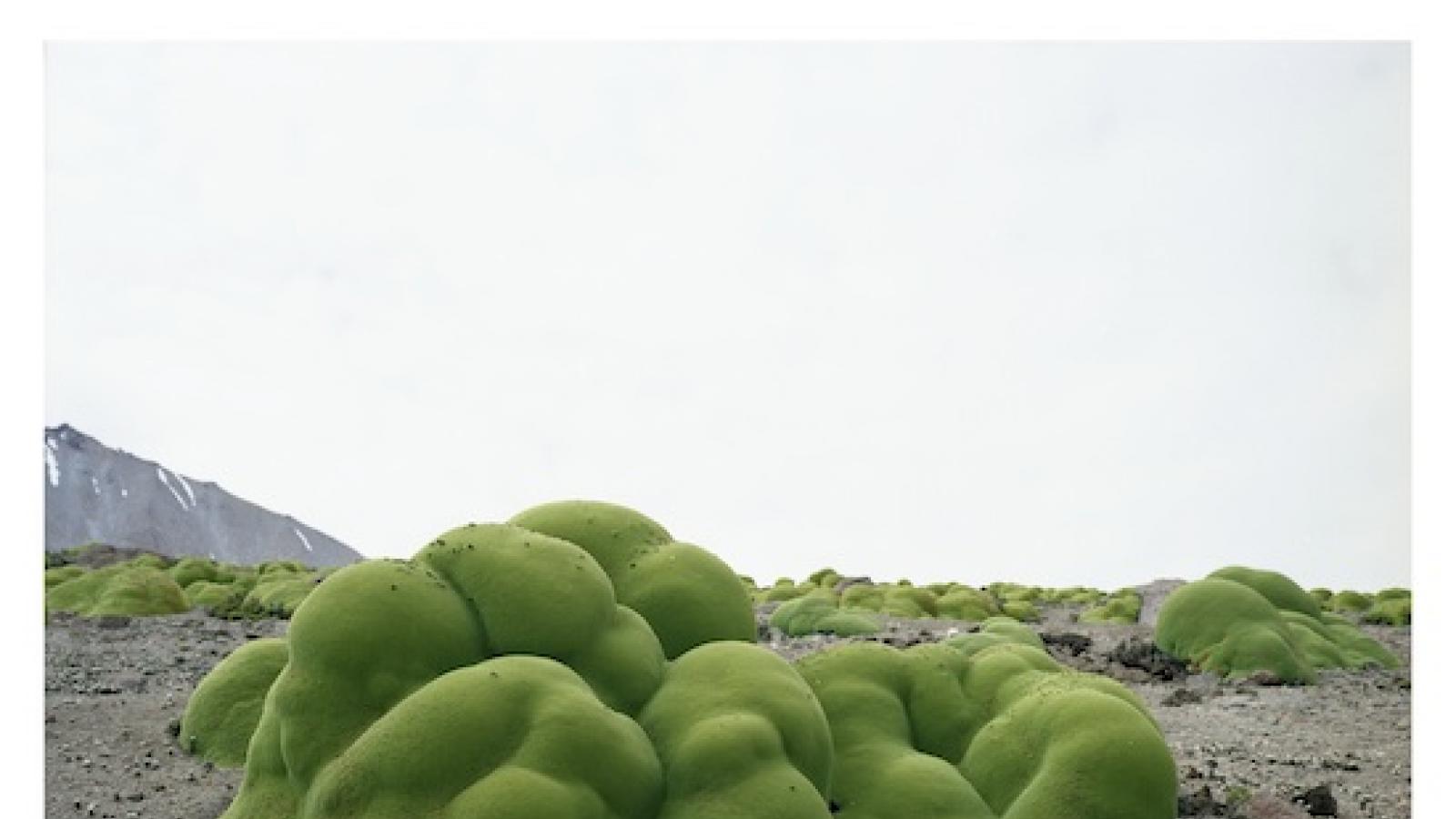

together yourself. In part, it's about the interconnectedness. These organisms live on every continent, which even I was not expecting when I first started the project, so learning that there's 5,500-year-old moss on Antarctica was a big surprise. A lot of these organisms live in very extreme environments, all sorts of places where we think life shouldn't survive—let alone thrive. I think we can't help but connect this perseverance—or underdog stories, even—to our own lives. I encourage this sort of anthropomorphizing of these organisms and their stories because I think that's what makes them relatable.

So, back to the idea of the importance of the climate issues. We hear these things like carbon-dioxide levels are rising. You hear "400 parts per million," and it doesn't really register what that means. But when you can look at this organism and say, "Wow, this spruce tree has been living on this mountainside for 9,500 years and, in the past 50, got this spindly trunk in the center because it got warmer at the top of this mountainside," there's something that's a very literal depiction of climate change happening right in front of you. It's observable. So I hope that that's going to be a way that people can connect to that as an issue.

I also hope the audience can internalize some of these messages—the values in the perseverance, the living through adversity that these organisms embody. There are a lot of positive messages to be gleaned from these long-lived organisms. They tend to grow very slowly. They're not very flashy. The oldest ones tend to be the least attractive. There are exceptions to all of the rules, but it's a great way to, I think, personalize something that otherwise, in terms of the numbers and the science, can be so abstract that we just don't take them in. So I'm trying to create a more personal way to connect. And that's also why I do a fair amount of writing in the book about my personal experiences and sometimes share some very personal things—because, again, I want to draw some attention to the fact that it's difficult to stay in deep time because we are people. We have immediate wants and needs, and things are happening to us and around us that we are constantly reacting to. And the work isn't meant to diminish that and say, "Oh, you should be more like the llareta." That's not the message. Rather, by forging a personal connection to such deep time scales, and these ancient individuals that are still alive and kicking with us here in the present, it's a way

to check in with something that connects us globally and temporally and transcends the things that divide us.

NEA: We talk a lot about how the science can enrich art, but I'm not sure we talk enough about how the work that the artist is doing can enrich the science.

SUSSMAN: One thing that was exciting, sort of midway through the project, was that I started getting scientists contacting me, saying things like, "Hey, why isn't our tree in your project?" I was like, "Oh, I hadn't heard of it, but I'll be right there!" Somehow, there's some different kind of communication happening. But even early on, I found scientists often aren't talking to each other as much as I'd expected. For instance, when I was looking at a clonal desert shrub in the Mojave, and then talking to another botanist in South Africa about a different but similar clonal desert shrub, and the two had never heard of each other or their work. And I said, "You guys should

talk." So sometimes, it's just that kind of networking.

I was very happy early on and through the project to have scientists say, "I can't be the person who's doing this with you, but I will share with you what I know. But this is a great idea. This makes sense. I'm happy to be part of it, and I'm learning more and thinking about

things differently." And now that the project is more developed, I've had a couple of scientists tell me, "I'm thinking about my work differently now," which is thrilling. I mean, I have no idea what direct effect the work will have, but I have definitely felt that something's happened. Some dynamic thing happened because of the work that may, in turn, impact these individuals' work in the future. And my hope is that the idea of looking at longevity across species can take hold as an area of research.

NEA: Who are some of the other artists who are working in this space that you find particularly interesting?

Sussman: One that I often think about is Trevor Paglen. … I was particularly interested in his work The Last Pictures, sending imagery up on a satellite to exist after Earth no longer exists. It is durational work of the longest sort—in other words, work that expands your way

of thinking. And often, it's just asking you as the viewerto ask some interesting and challenging questions. So I certainly appreciate that. Other artists accomplish that with more straight work, like Ed Burtynsky—certainly, his environmental landscape work, I think, is really impactful. There's another artist, Henning Rogge, whose work has been circulating a lot recently. He made beautiful landscape photographs where World War II ordnance had exploded, but have since been reclaimed by nature. And I thought that was lovely because it really tied in so many issues into one body of work. You have, on the surface, some beautiful—albeit a little bit strange— landscapes. Then, you learn, okay, this has to do with war and conflict. And then, it has this third layer of ecology and nature reclaiming something over time that we, as humans, have torn apart in an instant. I love that layering. The idea of the palimpsest is something that I think about a lot in my work. It's certainly applicable

here, and dealing with the medium of photography adds another tension—where you have something that's so layered, yet contained in this two-dimensional form.

NEA: Can you say more about that idea of palimpsest?

SUSSMAN: When I started thinking about the palimpsest in terms of my work, suddenly it just really made sense to me thinking about layering. There's one definition of the palimpsest, which is the object—old scrolls, these parchments where you had text covering other text. And a lot of times, it was employed when somebody disagreed with the first layer of text—they would simply write over it with text that was more to their liking. But the secondary definition involves things containing layers of their own history within themselves. And that, to me, was so poignant.… with the Oldest Living Things, there are layers of layering happening. You have the lives of the organisms themselves, and they contain their own histories within themselves,

so they are in and of themselves palimpsests. But then, you take this other layer, which is this seemingly very shallow layer of a photograph that's made in the split second of an exposure. I mean, it's also something I think a lot about—the temporal tension of that. So, you have these thousands of years required to make the

organism in order to take the sixtieth-of-a-second exposure to make this photograph. And it's another layer, but you realize it's not just the surface. It has all of that history contained within itself. And it also has to do with the engagement of the audience as well, because

you can just see the picture and say, "Oh, that's an interesting tree" and leave it at that. But the more time you spend with it, the more rewarded, I hope, that you'll be. For instance you read the title, and think, "Oh, wait a second; that's 2,000 years old," or "That's 10,000

years old." Maybe you then go to the book and read the essay on it and then learn something else. And maybe you do some research on it, or maybe you see it the next time you're traveling. That's just one organism. And then, you have all of the other ones as well. You can also think about the layering of all the disciplines involved: the art,

science, and philosophy. So yeah, it's sort of like those French desserts that have the thousand layers, mille-feuille. It's like pastry. It's like a really good pastry.

NEA: Can you talk a little bit about what you're working on now?

SUSSMAN: Through doing the Oldest Living Things series, I was thinking more and more about deeper and deeper time. The oldest things in the Oldest Living Things are bacteria that are half a million years old. It's very impressive; not going to knock it. But in some of my other research, I uncovered things like the stromatolites, tied to the very beginnings of life on Earth. The oldest still-living stromatolites are between 2,000 and 3,000 years old, but stromatolites first appeared on Earth 3.5 billion years ago, and are credited with oxygenating the planet. That took 900 million years. Stromatolites are part biologic and part geologic, comprised of living

cyanobacteria bound together with non-living sediments like silt and sand. The bacteria perform photosynthesis, which, in essence, gives us the origin story of our atmosphere, paving the way for the rest of life to come.

In addition to reaching back to the beginning of life on Earth, I also found several ties to outer space that I wasn't expecting. Those lichens from Greenland that I had mentioned earlier were sent to outer space not so long ago and were exposed to outer-space conditions. Astrobiologists are studying the beginnings of life on Earth by sending extremophiles out of Earth's atmosphere to see if they survive, and asking if they can survive re-entry. The stromatolites and the lichens got me thinking about time and space, and also philosophically where time and space start to slip, and how astrophysics and the philosophical thinking get a little bit intertwined.

The project that I'm currently doing—I don't know what the outcome will be, but I am very happy to be a part of the LACMA [Los Angeles County Museum of Art] Art + Technology Lab grant program. I just spent a month out in L.A., where I was hanging out at SpaceX, NASA

JPL [NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory], and CalTech, talking to astrophysicists and engineers and just trying to get some ideas about our human perspective and understanding of time and space—and where we get that wrong, where our observation, in particular, itelling us something that is not correct. One example—and this is something that I've been thinking about for a while now—is the idea of dead stars. When you look in the night sky, if you have a telescope or you're some place that actually gets dark, that all the stars that you see in the sky aren't necessarily all there.

NEA: Because it's taken so long for the light to get to Earth that the star has already burned out.

SUSSMAN: Exactly. So that, to me, is a really nice example of people observing this thing that seems to be happening right in front us— that we observe to be true—but it's actually not. One of the things I'm considering doing is to create a light installation

about dead stars, using accurate scientific information to map out the dead stars in the sky and mediating it through an aesthetic experience. Perhaps I'll add a durational element, where a day in the gallery equals a million years or a hundred million years. When I was

discussing the idea with an astrophysicist at JPL, he upped the ante and said, "What about dead galaxies?" I was like, "Wow, I hadn't thought about that." So it's still in the early stages, and that's the kind of thing that I'm also just trying to learn more about. There are

all sorts of things that are just absolutely mind-blowing, but you need a gateway in, to figure out what questions to ask. There are all of these phenomena that I'm just starting to learn about, too, that an astrophysicist or an engineer might know about but aren't really part

of our basic lexicon of understanding how space works and how little we know about it. So the idea with the LACMA Lab is to be immersed in these different areas and, hopefully, just trigger some ideas and forge some relationships and generally get exposed to things that we

wouldn't be otherwise. It’s unusual and invaluable for an art institution to support the creative process without a concern about specific outcomes. It makes me think of the concept of "blue sky" science, where the immediate application of the work isn't clear, but rather is driven by the curiosity and a sense—intuition if you will—that

the work will be valuable. LACMA is facilitating the same thing for art.

NEA: More than a decade into the Oldest Living Things project, how have your thoughts about the relationship between art and science changed?

SUSSMAN: Just as there's good art and good science, there are good art and science collaborations, and bad art and science collaborations. In my opinion, the good ones are where something is being brought to the table on both the art and the science sides. So it's not just artists getting enamored with scientific tools and using

them for purely aesthetic reasons. And it's not just the scientist making the research look pretty. I think the best projects are bringing something new and enriching aspects of both the art and the science. The more scientists that I've worked with, the more I've

realized that artists and scientists share a lot of the same values in terms of the way they approach their work, the things that are important to them, the kind of risk that's involved. The hope of discovering something new, happy accidents—all of these things are shared in art practice and science practice. And I think as more artists and scientists collaborate in more nuanced and sophisticated

ways, we're going to see more and more value coming from those relationships, likely in ways we wouldn't expect or predict. For me, the Oldest Living Things project is a perfect example of why it's good to be working in a cross-disciplinary environment. The

scientists immediately recused themselves and said, "I'm not qualified." But for myself as an artist, I was able to come in and say, "I just have this idea, and I'm just going to follow it whatever direction it takes." I don't have to be following rote scientific protocols when deciding I want to look at this clonal desert organism and this coral and these bacteria. That's the benefit of coming at

something from a different angle. Just taking even a quarter turn and looking at something from a different perspective can end up being incredibly valuable. This doesn't diminish the scientific method and specialized methodologies, certainly. But the more and more we can

collaborate, I think, and be a little more porous between the disciplines, there's just more and more opportunity to broaden our understanding of the world in general. We all live transdisciplinary lives; no one thing defines us. So why not embrace transdisciplinary work? Whatever your field, there is always value in some outside perspective.

This interview initially appeared on the Art Works blog in 2014.