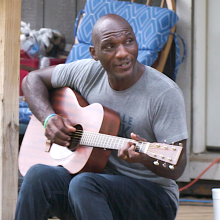

Art Talk with Musician and Founder of Art as Mentorship Enrique Chi

Photo of Enrique Chi by Adam Gundersheimer

If it were not for his father’s knowledge of guitar, Enrique Chi said he may not have been able to learn to play the instrument when he immigrated to the United States at six years old.

“I don't think we had the resources for the music education that I would have desired to have. Who knows what I would have done if my dad hadn't played and couldn't have showed me, put your finger more like this, at home?”

The love and knowledge of music that Chi’s father instilled in him would eventually lead him to start his now Latin Grammy-nominated band Making Movies. The band, born out of Kansas City, Missouri, proclaims on their website that they make “American music with an asterisk”—mixing classic rock with a mix of other sounds, including Latin and African rhythms and musical traditions.

In 2017, after years of hosting music camps for local youth with Mattie Rhodes Center, Chi founded his own nonprofit, Art as Mentorship, to formalize the curriculum the band had been teaching and expand their programming. One of these programs is the AMERI'KANA concert series, which received a $20,000 NEA grant and featured an array of musical traditions, such as gospel, blues, son jarocho, and Norteño, and included renown artists such as 2021 NEA National Heritage Fellows Cedric Burnside and Steve Berlin of Los Lobos.

Chi sat down with us via video conference to discuss the formation of Art as Mentorship and his mission to honor the many sounds that make up American music.

ART AS MENTORSHIP

[Making Movies] is 12 years old, and a couple years into being a band, we wanted to make a music camp in an immigrant neighborhood. I didn't grow up in this neighborhood, but I moved to it and I started volunteering at a community center. The immigrant stories of the kids I was hanging out with in the after-school program, they were a lot more challenging than mine. My dad had U.S. citizenship when he brought us to the United States, so I was able to get naturalized citizenship. It wasn't easy, but in the grand scheme of immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers, [it was] a walk in the park, comparatively.

I talked to the band, and we had been touring a little bit, and we had seen other cities have programs, and we're like, "Let's just do something, we could DIY like a music camp or something." We did, and that was ten years ago.

Six years into it, the community kept asking us if could we do more. The only way to do more was to create an organization. Four years ago, I took the plunge and started [the nonprofit Art as Mentorship] and built a board of directors. Then we used a concert to raise the money to do a 12-week program, which at the time was the biggest thing that we'd done, and it was really successful.

We partnered with our local radio station, 90.9 The Bridge, because I didn't want the kids to feel like they were at the back of a community center with crayons and toys and stuff. I wanted it to feel real and professional.

If I were to really look at the big picture, it's the same thing that happened in that first music camp, we just systematized it. We're just creating a space for kids to feel real comfortable expressing themselves, and that seems to still be the most important part, curriculum aside, recording studios, famous mentors, bigger concert opportunities, etcetera.

MAKING SPACE

Maybe four or five years into the camp, the parents of some of the kids would say this was life changing, or this changed my young person. We thought, well, what is going on? What have we tapped into?

We made the camp about songwriting as a way to level the playing field for kids who had never played music with kids who came with a lot of musical experience. Everybody could participate in the songwriting and the creativity, the lyrics, the melodies. What was happening is that we gave kids a space to be celebrated for their vulnerability. They were writing about what was going on in their neighborhood, or in their families, or what they were going through, and then they're applauded for it.

The professional mentors, the recording, the performances aside, the space where it's okay and normalized to say out loud your emotional processing–that's the magic sauce. The curriculum is really grounded in an art therapy approach.

Students from Art as Mentorship's Rebel Song Academy program in the studio. Photo courtesy of Art as Mentorship.

I think that that is probably the most important work that we're doing because when kids feel like they have a voice and they feel empowered and encouraged to use it, then I think you get a better community member in general—someone willing to speak out when they see things that are not right, somebody willing to speak out for others' injustices and those kinds of things. Above everything else, I hope that that's what we're creating. And if we accidentally create amazing musicians, that's a great byproduct, but this is the heartbeat of it.

Music is a vehicle for social change because it has always been a part of us pushing a reset button, of reassessing what we're going through internally, of communicating to one another our emotional processes. It's the oldest technology we have to communicate across great distances.

My love affair with music starts from that place. Because music can physiologically change your brain, I think it's important because it can disarm you.

I don't think a song can change the world, but I think people feeling like a part of a community and feeling comfortable raising their voice can change the world.

MEANING OF AMERI'KANA

Our band [Making Movies] formed in Kansas City, Missouri, of all places. We started touring, and sometimes we'd realize that we'd have a song in English, and the radio station [would put us on] the Spanish show or the Latin show because some of our band members are Latino. But this is a rock and roll song in English! Why are we in the Spanish show?

One time we played [a festival], but it was a small tent in the corner of the festival that was muddy, there weren't waters, and little logistical things were screwed up. We were like, "What is going on here?" Then I walked outside this little tent at a big festival, and it was “the culture tent.” I thought, it shouldn't be a culture tent. This is all culture, but certain cultures are culture, and certain cultures are “normal” or something.

So we made an album, and we called it ameri’kana and spelled it like the way it's phonetically spelled in a Spanish dictionary. The message is, American music has always included Spanish music in Spanish, and it should continue to do so. From its inception, [America] always been this mix of culture. And if we're still a mix of culture, that's what American music is.

We wanted to recreate the initial event that helped us start [Art as Mentorship]. We wanted to do it bigger, and we decided to use that brand, Celebrate AMERI’KANA, to emphasize this.

We wanted to curate a mix of Black and Brown music. When I play with a blues musician, I feel a kinship. When I play with a Peruvian folklorist and flautist, I feel a kinship from Panamanian roots. I can hear them as dialects of similar languages.

Musicians always feel that way, but why aren't festivals curated that way often? We wanted to curate that way to make a statement for our city, make a statement to the youth who perform at the event and who go through the Rebel Song Academy. All of these languages should be on equal footing in the American music landscape because they all are a big part of it and should all be celebrated in the same breath.

Steve Berlin of Los Lobos plays with Making Movies on stage at Celebrate AMERI'KANA. Photo by Diana Gonzalez.

We had D Smoke from Los Angeles, so that's hip-hop music. We also had members of Los Lobos and Mireya Ramos from Flor de Toloache – she's half Mexican, half Dominican, and grew up in New York City, by way of Puerto Rico. [Flor de Toloache] is a Latin Grammy-winning, Grammy nominated, all-female mariachi band. We opened up the show with the Sensational Barnes Brothers, and really the whole Barnes family are staples of the Memphis gospel scene. Their mother sang with Ray Charles, and she came with them and sang.

It sonically made sense. You heard gospel as this foundation, went into hip-hop, and then went into this kind of collaborative show where D Smoke walked on stage with Los Lobos and Ozomatli members, and it was really, really vibrant and fun.

We're excited to carry that message forward because the musicians, we all feel it, and the audience felt it too. It felt electric—let's just keep remembering how connected we all are.