Looking Twice: A Conversation about Photography at the Library of Congress

You’ve no doubt heard the popular saying, usually in response to an unwanted stare, “Take a picture; it’ll last longer.” The Library of Congress, however, is proving the truth of that statement in their recent exhibit Not an Ostrich: And Other Images from America’s Library, which lets you stare at the pictures as long as you’d like. In partnership with the Annenberg Foundation, the library’s extensive photography collection was pared down from 15 million to 3,000 to 440 images for the exhibit. 70 of which are on display in the library’s Jefferson Building. All of the selected photos can be viewed via slideshows throughout the exhibit hall as well as online. The show’s eccentric title comes from a 1930s photo of actor Isla Bevan regally holding a bird that looks to be an ostrich. Looking closely the bird is revealed to be a rare Floradora Goose, and that’s exactly what the show’s curators wants to encourage—a closer look at photographs many of which we think we know to see what else is revealed.

The pictorial scrapbook of American history is vast and holds many deep stories and monumental events. Ranging from an iconic photograph of Tina Turner performing with one of the Ikettes to a photograph of a 2008 casino boat floating on the Mississippi River, the photos included in the exhibit are a melting pot of political strife, inventions, renowned entertainers and musicians, and the evolution of America’s landscape and people through the years.

We spoke with Anne Wilkes Tucker, curator emerita of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Helena Zinkham, chief of the Prints and Photographs Division at the Library of Congress, about their roles in curating the exhibit, the “why” for people to visit this exhibit, and the value of photographs in telling America’s story.

National Endowment for the Arts: What is the origin story for the exhibition Not an Ostrich: And Other Images from America’s Library?

Helena Zinkham: [In 2013, a] wonderful photographer named Carol Highsmith was being interviewed on a CBS morning show and Wallis Annenberg—chair of the Annenberg Foundation—heard that program, and was so intrigued by the pictures that she saw, that she asked to learn more about the photo collections at the Library of Congress. I would like to [share] a quotation from Mrs. Annenberg about how much she valued photography: “A great photograph does so much more than capture what's in front of us. It captures what's deep inside. The trials and the triumphs the naked eye rarely sees.” When I heard that quotation, I knew we had a fabulous opportunity, someone who deeply understands photography.… At the end of the day, this was a really important opportunity to share our photography collections with a new audience, and people who probably have never come to Washington [,DC]. The concept for Mrs. Annenberg was presented as, “Please show people pictures they've never seen before.” Once Mrs. Annenberg arranged to hire Anne Tucker, we started the research. And we did in fact find close to 300 photos that had never been shown online before.

Anne Wilkes Tucker: My first book [The Woman’s Eye] was in 1973, and I used the Library of Congress archives for that work. That began a love affair with the Library of Congress as an extraordinary repository of the history of America and the history of photography. So, it met two criteria that Mrs. Annenberg had in all of her projects. And she had, unbeknownst to me, heard me give a lecture once, and called my director and asked if she could borrow me to curate her first show at the Annenberg Space for Photography. So, it was putting together two organizations that I had wonderful working relationships with and working with Helena and the extraordinary staff in the Prints and Photographs Division [at the Library of Congress]. We worked out that I would work closely with curator Beverly Brannan. I came almost once a month, sat at a table, and photographs were brought to me or I was directed to cabinets that had [stereographs, portraits,] and news photographs. It was a collaborative experience that went on for about a year and a half. The really fun part was that in the beginning, because they didn't know me, staff would come up and say, “Can I show you my favorite photograph in the collection?” I learned so much American history. There were some very serious photos [that depicted] race issues, bomb issues, and political issues, but there were also [photos that were] just plain fun.

NEA: There’s an interesting section of the exhibit that features photos of photographers themselves who are really embodying the spirit of “anything for the shot.”

Tucker: We added pictures of people who are at high risk to take a picture, like a man who's dangling on a rope over a canyon in the West. We wanted to remind people that this was a photography exhibition and there were individuals involved, men and women, who were dedicated to being photographers, and how you express yourself and document the world through photography.

Zinkham: An impressive feature of the collaboration with the Annenberg [Foundation] is that they made a 30-minute movie to represent photographers, visually, as a reminder that these pictures came from people [and to show] the vulnerability of the photographers and how much in the thick of the story they become. The video has interviews with at least five of the photographers who are still living and can tell their own story. The opportunity to include their voices—that was a gift.

NEA: How do photographs tell us about history in a way that other documents can't?

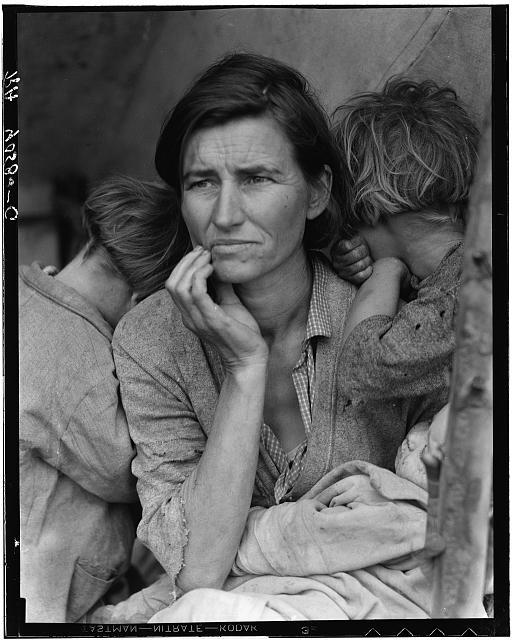

Tucker: It preserves people that are important to history, such as [the Apache leader] Geronimo. There are several photographs of 19th-century American leaders and Indigenous leaders. There are photographs of Dr. Martin Luther King. There are photographers who create projects, some of them long term, such as Danny Lyon who worked for SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] and for John Lewis. He also then moved on to photograph prisoners in Texas prisons. Then there are the people who just carry a camera all the time in their city and see a picture and bring that camera up. In doing that, you get fashion, you get density of population, cities, small towns, Thanksgiving dinners, ranchers, the Midwest, American skyscrapers, and bridges. The building of America. So, there's the immediate response to the photographer who may not be thinking about history but thinking about what would make a good picture that would draw somebody in. But the life of the picture is where the Library of Congress comes in. Because when those pictures are scanned, some of them have copyrights, but others don't. The most requested photograph, Dorothea Lange’s photograph of a migrant farm worker in 1936, has been reproduced thousands of times in the United States and people in other countries have taken the format of the picture and made it into an African woman or a Spanish woman because the [image of a] mother grieving for what she can't do for her children is universal.

Zinkham: Photography is a universal language, and life rushes by [but] photographers have really frozen a moment, whether they posed it or whether they were on the scene when something unexpected happened. I've had a really good time lately, going through the exhibition even without [the wall text posted], watching exhibit goers walk up to the photos. Before seeing the exhibit, many exhibit goers have never noticed the baby in the Migrant Mother photo; they'd seen the mother and the two children [due to it typically being] reproduced small. I love the way photography can be appreciated in a quick glance, and also a deeper conversation. In addition to the products themselves, Anne arranged the 70 full-size pictures to have stories that… amplify [the photograph]. I love that this exhibition has provided all of the ways that you can interact with a photograph.

Tucker: My empathy shifts relative to my age. When I look at Gordon Parks’ photographs of Muhammad Ali's battered hand, I first saw them years ago from a recent fight. Now, as somebody in her late 70s, I think about Ali in those late years when those hands were crippled. I have a whole [new] perception of what that story can be about. You can go through the exhibition in that way, and I'm sure that parents, grandparents, and kids literally see different things. We don't see with our eyes, we see with our brain— the light goes directly through our eyes to the brain, and how it’s processed depends upon our life experiences and our knowledge. If you've seen the movie Seabiscuit, you will have a different response to the photograph of Seabiscuit. But if you know the whole story, then you go “Oh, that's the real horse.”

Migrant Mother. Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age 32. Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

NEA: My favorite photo from the exhibit was Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother because it showcased the face of mothers that can be found in every time period; stressed, thoughtful, and wondering about what lies ahead. It leaves so much for the viewer to interpret and empathize with. Do you have a favorite photograph in this exhibit?

Zinkham: The portrait of Harriet Tubman is one of my favorites because it is a unique photograph that shows her at a younger age. She has such a presence in the way she sits towards the camera.

Tucker: A picture that I was happy to see in the popular list is related to the inventor of the radio, [Guglielmo] Marconi. A couple is dancing with this giant weighted radio between them and earphones. In the digital world with everybody having their [headphones] in their ears, I just hope that some of the audience might put together the extraordinary progress from the invention.

NEA: With the evolution of technology and the advancement of social media platforms, such as Instagram, why do you think people will still come to see this exhibit in person?

Zinkham: It is a completely different kind of engagement with photography and pictures that you think you know, and you will see them in different ways. The three dimensionality of the exhibition space is making a huge difference. Each time you go around the corner, there's a surprise.

NEA: What particular themes and messages do you hope visitors take from the exhibition?

Tucker: In this digital age, I hope they'll understand the longevity of photographs and how some of the photographs in the exhibition are what Dorothea Lange called second lookers—pictures you want to return to; pictures you can even see differently at a different time. Then, in terms of their own experience, maybe they'll take fewer pictures and think about them more.

Zinkham: Photography is so ubiquitous now, thanks to our cell phones. I hope that when people come to see the exhibition, or look online, if they're not able to come to Washington [DC], that they slow down for a minute and look; rather than glance. I hope that we can accomplish building appreciation for the impact of photography and come back to the benefits of looking twice, not just looking once.