Show Yourself: A Conversation with Illustrator Marcos Chin

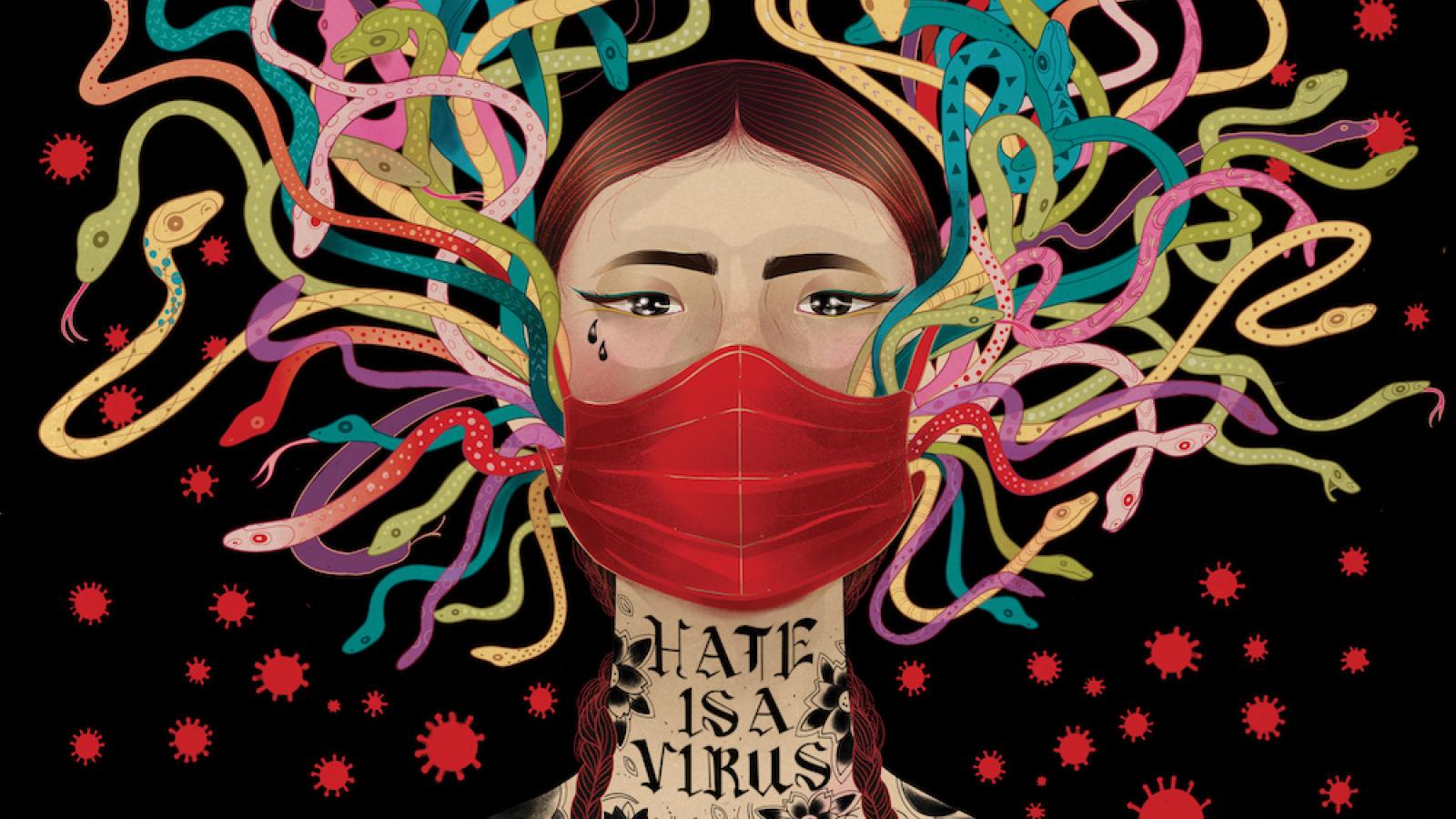

"Hate is a Virus" by Marcus Chin, for #HATEISAVIRUS.

Although Marcos Chin had always wanted to be an artist, as he was growing up in Canada, his family had other ideas. As he noted during our video call, his father's advice was, "You need to do something that's not a hobby." Chin did try to take the safer business-focused route, but eventually found himself applying to art school in secret. The gambit paid off. Today his portfolio boasts work for clients such high-profile clients as Starbucks, Kiehl's, and HBO, among many others. Whether working in analog or digital formats, Chin's work is dynamic, colorful, and representative of the multicultural milieu he grew up in with a diversity of body types, skin tones, and sexualities represented. In the interview below, Chin talks about learning to be comfortable with revealing more of himself in his work, the challenges of financial security, and how his measure of success has changed over the course of his career.

Marcos Chin. Photo courtesy of the artist

NEA: What’s your origin story as an artist?

CHIN: I always knew I wanted to study art in some capacity. I love fashion, animation, but, you know, I come from a working-class family of immigrants. My parents didn’t feel as though art could get me a real job. They didn’t believe that I could make money through my pictures. The irony of it is that [when our family was in Mozambique] my dad actually worked as a draftsman. He was in applied art. When he was young he made these beautiful drawings and paintings. When I visited my [father’s] family, I saw some of his paintings and drawings on their wall. [When I wanted to be a professional artist], it was, “Nope.” <laughs> You need to do something that’s not a hobby. You need a fallback plan. You need all of these nets set up in case you don’t make it.”

I went into the Fine Art Department at York University, but it just wasn’t a good match at that time for me. I decided to step outside of [the arts], and I took some economics courses, business courses. But I was just miserable, so I ended up applying to art school behind my parents’ back. When I got in, it was a little bit like a teenage angsty thing, you know, like, a kind of rebellious type of moment for me. But I thought, “You know what? I’m just going to give it a shot.”

NEA: How do you describe your work as an illustrator?

CHIN: I tell stories through the pictures that I make. My entrance into the industry, the catalyst was really money. I come from a family that didn’t have a lot, and my intention was to be able to make money through my work. I really didn’t give myself a choice. What was happening early on is I was making work, but it was a struggle because it didn’t really reflect who I was as a person. It was just a mishmash of my instructors’ styles. So I wasn’t happy making the work, and at the same time I was also not making <laughs> much money. Now it’s become more mixed media [and I work in both] analog and digital. I started making money and seeing more success within that space, but the work that I was doing was rooted in commercial projects. It was mostly fashion and lifestyle types of pictures I was doing back then. I was going out to the gay clubs and all of my twenty-something-year-old experiences were showing up in my pictures. But I realized that as I was growing and changing as a person, my work was staying the same and I needed to shift out and pivot. That’s when I really started to be more intentional and purposeful about creating projects that reflected who I was as a person. When I was first coming up as an illustrator, I was advised by an agent of mine to not show my queer sexuality through my illustrations because she was afraid that it would hurt my career. I understood that. It was coming from a place of care, but I realized that illustration wasn’t a large enough container to hold the things that I wanted to say and the person who I was becoming. [I’ve become] very intentional about giving space and time to make personal things that a lot of people don’t see.

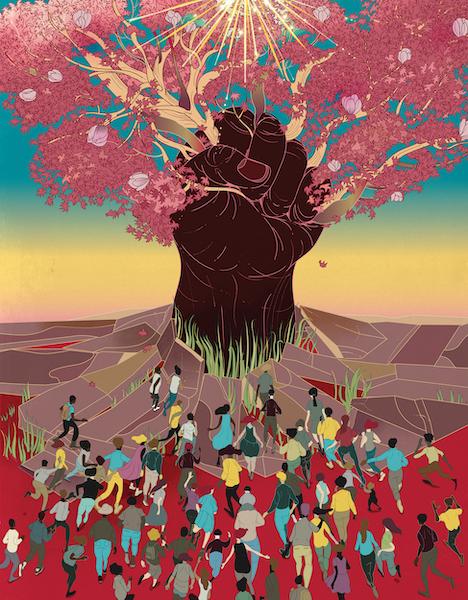

"Resist" by Marcos Chin, for the Penn Stater magazine.

NEA: How does your identity as part of the LGBTQ+ community inform your work?

CHIN : I’ve been working in the industry for about 18 years, and I can say in the last couple of years it’s really shown up in terms of people very specifically saying, “Hey, Marcos, we want to work with you...” because of XYZ reasons. Where I was raised and spent most of my life, it was incredibly multicultural, so in terms of figures and characters, I was drawing what was around me. It just felt natural to include diverse communities of people in my work. But it never occurred to me to include what the sexualities of those people might be, even if they were drawings. Now it’s speaking much louder to me. Not every project is appropriate for me to express [my sexuality] within the project, but I try to do it whenever I can. Because so much of our lives are so entangled with social media and the digital and personal/private is becoming so blurred, it’s also encouraged me to show and display that part of myself more openly in the foreground, my sexuality, my body, my race, my skin color, things like that.

NEA: How do you think about success and failure in terms of your art practice?

CHIN: I invited a former student of mine to come speak with my students. She used the expression, “Without financial competence, you can’t have creative confidence.” To me it’s such a concise and eloquent way to describe how I’ve lived most of my life, because success for me was very, very, very much rooted in the trappings of capitalism, of money, of being validated by others and winning certain awards and medals. It still is important to me, but I felt like I spent so much of my time and energy pouring myself into these spaces that I’d be burned out. And then the cycle would happen again. Success nowadays is more about how I’m feeling while I’m making the work that I’m making, because I know I can’t always enjoy it. It’s also reflected in how my body feels, the relationship that I have with my partner, my dog, <laughs> you know, my family and friends. I was doing much better financially years ago, but I also remember feeling really tired all the time and I was also unhappy. Nowadays it just doesn’t feel that way because I think that I’m more in touch with other things in my life that bring me joy.

I think voices just became too loud in terms of, “Am I really good enough?” That was also one of the reasons that I [started to pour] more time and energy into making personal work, because when I was doing that exploring and focusing on my curiosity, I no longer heard those negative voices in the background. Also, I was really fortunate that early on in my career I had been commissioned for a project that was able to lift me out of a working-class economic space. It changed my life and allowed me the opportunity and privilege to have a different kind of relationship with money.

NEA: I know that teaching is also part of your practice. What do you want students to take away from working with you?

CHIN: The first one is to show parts of themselves in their work. To know that there’s value in that, and that is sort of coupled with the things about themselves that might make them feel uncomfortable or they might overlook even as unimportant. [Those things] can actually be really great power sources to create work. Also, I’m not the kind of teacher who students [work with] because they want to learn how to draw and paint. It sounds like a weird thing to say, <laughs> because I teach in an art school. When they step into my class, I want them to feel like this is a place that motivates and inspires them to make work.

NEA: I think it’s fair to say that we live in tumultuous times for a number of reasons. Many in the arts are using this as a time to re-evaluate their values and really scrutinize legacy ways of doing things. As we re-set, what are you seeing and what would you like to see going forward?

CHIN: One of the things that has come up for me is representation. I really am starting to see a lot of non-white artists’ work in spaces where I never used to. I’m hoping that the city will also continue to support small businesses and artists. Right now NYC Cultural Affairs [has] programs that are giving grants to hundreds of artists to create artwork on barriers and scaffolds, and that type of thing. I think that’s amazing, and I want that to continue to happen. Also [I want art schools to] bring in different voices from different life experiences. I know that people are calling [to commission me for work because I have Asian roots] in a way that can make me feel tokenized. It’s a complicated feeling because I know that a few years ago, at least within the illustration industry, and I can probably say that in so many other industries too, it looked so different. There wasn’t as much space as there is now for someone like me, and I can feel and I can see that the circle is growing wider and wider so that we can have more people come in.