Back to School Grant Spotlight: Imagination Stage

Four student actors embrace in the Pegasus Ensemble production of Hoodies. Photo by Jeremy Rusnock

After producing a talent show at her children’s elementary school, Bonnie Fogel noticed that there was an outpouring of interest for the aspiring youth artists to receive more performing arts training. Fogel decided to meet that need by founding Imagination Stage (formerly known as Bethesda Academy of Performing Arts) as a place where young people could explore their interest in the arts. In a 2012 podcast with the NEA, Fogel explained, “Our mission has always been to unleash the innate imagination that every child is born with, to nurture that imagination through creative practices.” From its inception, Imagination Stage, based in Bethesda, Maryland, has remained true to its core mission of creatively unlocking the imaginations of students and meeting arts education needs, including programs for youth with disabilities, a professional theater focused on children's performances, and the opening of a 42,000-square-foot arts center.

At the heart of Imagination Stage’s programming is the belief that arts education serves as an effective vehicle in helping youth find their personal narratives. As Access and Inclusion Senior Manager Shanna Sorrells explained, “Connections to the arts can deepen a child’s understanding of the world and their place in it... The arts also allow a student to step outside their comfort zone and experiment with new risks. This allows them to fully discover who they are and to be seen in a new light.”

In May 2023, the organization received an Arts Endowment grant to support the work of the Pegasus Ensemble, a two-year conservatory training and performance program designed for high school students (ages 14-21) with cognitive, developmental, or physical disabilities.

We spoke with Sorrells and Joanne Seelig Lamparter—artistic director of Education and Theatre for Change—about the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, the ways in which their programming is inclusive and accessible, and how Imagination Stage continues to step out of the traditional box and engage with the community.

NEA: How does Imagination Stage align its professional theater experiences to create academic curriculum objectives for elementary school-age youth?

JOANNE SEELIG LAMPARTER: The artistic team commissions and selects scripts for professional productions based on literary merit, originality, and artistic innovation. Appropriate themes for theater for young audiences often revolve around finding personal identity, creative problem solving, and building positive relationships with adults and peers. The education team analyzes the season scripts to uncover the curriculum ties at various grade levels. They produce a Student Learning Guide for every show during the school year that links to specific Montgomery County Public Schools and District of Columbia Public Schools curricular goals. Pre- and post-show activities are offered to teachers. With our annual Learning Through Theatre program for over 5,000 Title One third graders, we also design pre-show workshops that take place in the theater immediately before students see the show.

NEA: In what ways does Imagination Stage make its programming and shows inclusive and accessible to individuals with diverse needs?

SHANNA SORRELLS: Imagination Stage empowers young people and their families to make choices that best match their own needs. We recognize that every child who comes through our doors has their own unique self-expression and way of experiencing the world. All children, including members of the disability community, are welcome to enroll in all of our theater classes. Inclusion is just one part; accessibility is the second part of the equation. We strive for all students to benefit from instruction in a way that matches their needs. We also offer peer-to-peer classes as an option, which enables students with disabilities the opportunity to connect with each other and receive instruction specifically with neurodiversity in mind. We offer sensory-friendly shows and ASL [American Sign Language] interpreted shows as well. We have a quiet room situated in the theater for every show, and we keep auditory listening devices, headphones, and sunglasses on hand for every show so young people can continue to make choices for how they experience theater.

NEA: The COVID-19 pandemic changed the world as we knew it. In what ways has the organization adapted to continue serving its participants and audiences?

LAMPARTER: During the pandemic, we adapted in how we delivered our programs and services by shifting everything—from performances to camps and classes to virtual. Currently, all of our programs are being delivered in person again and interestingly, there hasn’t been an appetite for any virtual options. Families want a place to bring their children to be able to interact with others in a prosocial environment, which really can’t happen in a virtual space. Moreover, the pandemic gave us new inspiration for meeting the needs of all children in our community, and we are now delivering a plurality of programs in schools and other community spaces rather than just in our downtown Bethesda arts center. Our goal is to shift this balance to 50/50 by 2027 so our beneficiaries match the demographics of our community.

NEA: Can you provide us with a snapshot of the Pegasus Ensemble?

SORRELLS: The Pegasus Ensemble provides a safe place where students can spread their wings and fly. Learning in-depth theater arts techniques and life skills is a major focus, but the real treasure is forming bonds with peers. Teens develop a strong sense of community and belonging within a space where disability is not just welcomed, but celebrated! The final production at the end of the two years highlights their skills and strengths, and honors preferred communication modalities, whether it is speaking, using physical movement, signing, gestures, or communication devices–the stage is limitless!

NEA: How does Imagination Stage engage with parents and families to encourage support and involvement in their children's artful journeys?

SORRELLS: Families are the child’s first teacher and an important partner in any learning experience. When signing up for an Imagination Stage experience, we encourage families to disclose how their child best learns so that our team can staff and differentiate instruction as much as possible so that everyone in the room succeeds. We also encourage families to continue creative learning at home. When our youngest students leave a class, the caregivers are provided an “exit ticket” so families can ask a question or have their students show something they learned at home. Our project-based classes always provide families a chance to see an end-of-semester sharing in which not only the students perform something they learned, but families also get to experience a warm up and hear a reflection of the experience. This allows families to better understand the artistic process as opposed to just seeing a final product.

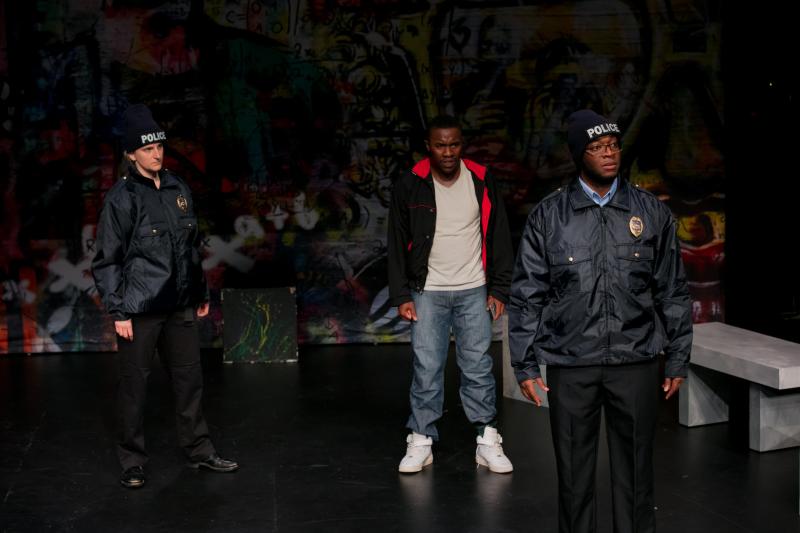

Katie Wicklund (left), Tre'mon Mills (center), and Carl Ackers (right) in Imagination Stage's Theatre for Change play 10 Seconds, about reimagining the relationship between teens and the police. Photo by Noe Todorovich

NEA: Tell us about the Theatre for Change program and its impact in the community.

LAMPARTER: Theatre for Change is comprised of three programs that use theater productions and educational workshops to bridge cultural divides and lift up underrepresented voices. Theatre for Change explores complex social justice issues to help build a new generation of compassionate, collaborative youths who are capable of changing the world. With this mission, Theatre for Change has facilitated over a dozen residencies, including workshops using theater as a tool to bridge relationships between law enforcement and youth (which informed the play 10 Seconds), residencies through Health and Human Services with newcomer youth in Montgomery County and the District of Columbia as part of our ¡Óyeme! program (which informed the play Óyeme, the beautiful), and Voices Beyond Bars workshops for young people involved in the juvenile justice system. We are the only theater company partnered with Montgomery County Health and Human Services’ Positive Youth Development team and are currently working across 18 classrooms with the ESOL [English for Speakers of Other Languages] newcomer populations. The program is also in nine District of Columbia Public School classrooms. Yearly, over 500 immigrant youth are engaged in our ¡Óyeme! residency program and this past year, nearly 7,000 middle and high school students received a Theatre for Change production in their school.

NEA: Could you briefly share a success story from a student who participated in the Theatre for Change program?

LAMPARTER: When we started ¡Óyeme! (our very first Theatre for Change program), we gathered a group of youth through Street Outreach Network with Health and Human Services. In this group were 14 teen boys, some of whom were gang-affiliated, and one young lady. She was a newly arrived young person who came from El Salvador fleeing violence and was now enrolled in Montgomery County Schools and living with her sister and sister's boyfriend. That young lady didn't say a word but was incredibly focused. She did all of the writing and drawing activities meticulously. For the following two years, she showed up to our ¡Óyeme! workshops every single week; often, saying very little but greatly contributing to the development of our professionally produced play, Óyeme, the beautiful. In this play, her story is greatly featured. She went on to speak on panels including in front of legislative staff from the Senate at a performance at the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center. Two years later, she co-led—with another participant in the ¡Óyeme! Program—a summit for migrant youth in the DMV [District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia] out of the Silver Spring Civic Center. This event was attended by over 100 young people and she bravely inspired and spoke in front of all of them. After graduating high school, she went on to pursue a degree in nursing at a community college.

NEA: Finish this sentence: Imagination is the key to unlocking…

LAMPARTER: The creative potential in the next generation of leaders.