Exploring Our Steps: A Conversation with Dancer and Choreographer Jean Butler

Jean Butler dancing onstage during the U.S. premiere of What We Hold. Photo by Nir Arieli

In the world of dance, where discipline and artistic expression intertwine, the journey from one form to another can be transformative. For dancer-choreographer Jean Butler, her dance journey began with an introspective exploration of her relationship with movement. Butler said, “I was never completely comfortable in ballet—I loved the movement, but I remember feeling very afraid of making a mistake and being called out. Irish dance felt different. The structure of the class was much looser, and the overall environment felt friendly, somehow more joyous and intimate.”

Butler went on to earn a BA from the University of Birmingham (United Kingdom) in Theater and Drama and an MA in Contemporary Dance Performance from Irish World Academy at the University of Limerick (Ireland). In 1994, Butler was part of the Irish dance theatrical production Riverdance’s creative team as choreographer and performer, originating the female principal role. Since 2006, Butler has pioneered a unique approach that merges culturally specific forms and contemporary dance. In 2016, Butler was honored with the Spirit of Ireland Award by the Irish Arts Center in New York and in 2020, she was inducted into the Irish American Hall of Fame. From 2010-2019, Butler served as an Adjunct Professor of Irish Studies at New York University's Glucksman Ireland House.

In addition to Butler’s roles as dancer-choreographer, she is the founder and director of Our Steps, a not-for-profit organization dedicated to connecting Irish dancers, teachers, enthusiasts, and scholars from around the world, while also introducing the contemporary expression of traditional Irish dance to new audiences. In January 2024, Our Steps received an Arts Endowment grant to support the work What We Hold, a site-specific dance production that is shaped and influenced by the organization’s work with building a living archive of Irish dance.

We spoke with Butler about her creative process, reconfiguring What We Hold for the U.S. stage, and the importance of celebrating and archiving Irish dance history.

NEA: What is your origin story as a dancer and choreographer?

JEAN BUTLER: I took two years of ballet before my mom took me to an Irish dance class when I was about six or seven. My mother grew up in Ireland and on the day she took me to my first Irish dance class, she happened to meet a friend she went to school with back home—someone she had not seen in over 20 years. I remember how happy she seemed and perhaps that’s why I found myself at home in Irish dance. There was an instant cultural connection that I did not feel in ballet. I also had an instant connection with my dancing teacher, Donny Golden, who is part of my life to this day.

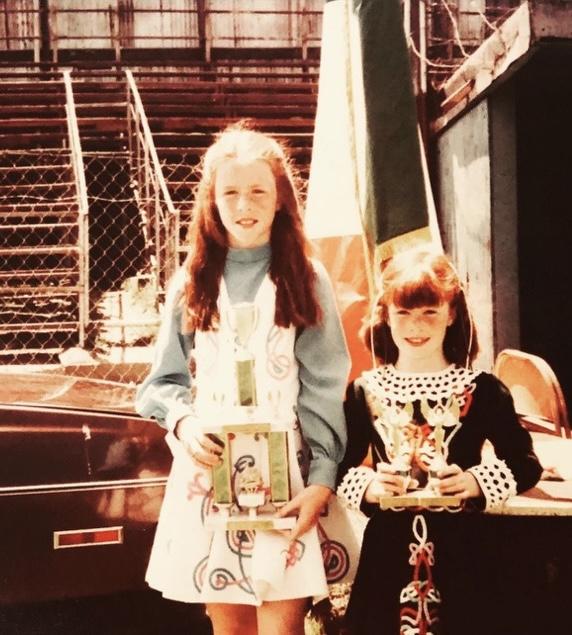

Jean Butler (left) and sister Cara Butler (right) as young girls holding dance trophies. Photo courtesy of Jean Butler

NEA: What are some of the misconceptions or stereotypes surrounding Irish dance?

BUTLER: Although I danced throughout my entire childhood and into my early adult years, I never thought of myself as a dancer and did not tell anyone I danced. For many years, the only people that did Irish dance, were either from Ireland or from the Irish diaspora. Irish dance was often ridiculed because of the traditional posture which does not incorporate the use of the upper body. It was an amateur dance form with little hope for a professional life outside teaching and adjudicating competitions. Performing was very limited and often involved yearly St. Patrick’s Day exhibitions. Riverdance changed this in 1996, but there are a generation of Irish dancers that carried shame around doing Irish dance. Even in Ireland, people would not let it be known they were Irish dancers. The popularity of the spectacle shows of the 1990s, globalization, and social media have exploded this notion that Irish dance is only for Irish people. People do Irish dancing now because they know what it is and they want to try it.

NEA: What inspired you to establish Our Steps? What community need did you identify that you believed your organization could address?

BUTLER: I had been teaching a class on Irish dance performance at NYU [New York University] for several years and in 2016, several incredibly influential Irish dance teachers on the East Coast died in quick succession. These were men that came from Ireland and changed the way Irish dance was danced in America. They were men I have known all my life, but I never had the opportunity to talk to them about their experiences and history in the form. It dawned on me that their personal stories and the steps they created would also die with them. Creating Our Steps and the archive was propelled by this moment in time, but it needs to be noted that so few resources were available on Irish dance. To this day, there are only a handful of books written on Irish dance and so few academic programs and dance festivals include Irish dance. I wanted Our Steps to change this, to invite others into our dance history, to create collaboration across all arts forms. I wanted to create a new space for Irish dance which was not about competition or large-scale commercial dance shows. I wanted to give back.

Our Steps Archive Residency 2018 at the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library. Photo by Megan Stahl

NEA: How does dance serve as an effective tool in advancing Irish heritage storytelling?

BUTLER: Under the auspices of An Coimisiún Le Rincí Gaelacha [The Irish Dancing Commission], Irish dance developed alongside Ireland’s fight for independence and is inherently inked to the history of the Republic. Dance, alongside Irish music, language, and sports were part of the Gaelic Revival organized and led by the Gaelic League which first met in 1893. The codification of the technique developed partly as a rejection of the anglicized stereotype of the time. Irish dance, with arms placed gently at one’s side, purported a civilized, in control, even elegant image of a people who were considered ungovernable by the English. Concurrently, the Irish traditional dancing body can be viewed at any point in time to reflect the zeitgeist of Irish identity. Another example is Riverdance, which coincided, or some would say ignited, Ireland’s first moment of economic stability and growth which became known as the era of the Celtic Tiger. The dance and most importantly the presentation of the dance (music, costume, and set design) was in line with a hip, contemporary, and confident Ireland.

NEA: Could you share more about what Our Steps does?

BUTLER: Our main programing revolves around Our Steps, Our Story: An Irish Dance Legacy Archive, which includes our archive residencies and oral history collection. Created as a series of documented workshops, the archive residencies see today’s competitive Irish dancers learn steps dating as far back as 1940. Each residency is a dialogue through memory and time—taught by elder master teachers and former students of eminent teachers and style influencers. The generational exchange highlights the uniqueness of how Irish dance is taught, learned, and imprinted in the body. It captures the idiosyncratic stylistic variations that once defined regional, national, and international styles of Irish step dance. Our oral history project is designed for Irish dancers to do something that they never get a chance to do—to reflect on their practice, to consider how our shared cultural history has defined our form, and to unearth what connects us to the collective consciousness of all dancers. We are very fortunate to have the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library as our partners. To date, this ever-expanding archive has created over 200 hours of video and audio resources of never before documented solo set dances and oral history interviews spanning seven decades of history from Ireland, England, Scotland, the United States, and Canada.

My intention in creating the archive was that it would be activated and used to inspire additional creative expression. Our Steps has a Special Project Program for performance projects, such as What We Hold, that directly engage the archive and bring awareness to this archival resource.

Our Dialogue Program initiates new writing on Irish dance from practitioners, dancers, and writers from diverse backgrounds and experience. The aim is to create an ever-evolving collection of found and commissioned essays that celebrate and interrogate ideas related to Irish dance and contemporary arts practice, reflecting where we’ve been, revealing where we’re going.

Jean Butler and fellow cast members dancing onstage during the U.S. premiere of What We Hold. Photo by Nir Arieli

NEA: How do your roles as an administrator and dancer/choreographer inform each other?

BUTLER: I think I am always thinking about collaboration and the key players I’d like to work with. How can I bring the most interesting, talented, and open people into the world of Our Steps or into a new performance work? When I am making work, I am constantly thinking about what I am learning from the group I have assembled, both on the performance and creative side. For me, a piece is unknown for the longest time, it tells you what it needs and it is my job to listen closely. All Our Steps programs are similar in this way—our archive residencies, our oral history collection, and our essay commissions—they all require the room to become what they need to be with the people involved. Each time is different and embracing that keeps our programs alive, present, and reflective of the lived moment and experience.

NEA: When choreographing, what is your creative process?

BUTLER: Choreography is becoming more and more about listening, letting go, and trusting my intuition. I can talk to the starting points for each work I have made over the years, but I never have a preconceived end point. I never start with music, which has been a constant in my process. The sound score is developed alongside the movement material. Choreography is also about the grind—the act of doing the work—chipping away each day to see what sticks. We can only know through the doing. My personal movement vocabulary is directly related to my history as an Irish dancer, which has been my only formal training in dance. My approach to creating work however, is through a lens of contemporary dance principles. It is the marriage of my past kinetic make-up and present sensibilities that inform much of what I do.

NEA: What We Hold first premiered at the Dublin Theatre Festival in October 2022. What sparked the idea of producing it for American audiences? Were there specific adaptations for the American premiere?

BUTLER: My work as a dance artist bridges the gap between a culturally specific form and a contemporary approach to choreography. Because of my history in both Ireland and New York, my work also bridges both countries. I am fortunate to have my work co-produced by U.S.-based and Irish entities, ensuring a presentation in each. What We Hold is a site-specific work with a limited capacity audience that requires four distinct and separate spaces. At the Dublin Theatre Festival, the show unfolded in City Assembly House, a Georgian mansion in the middle of Dublin, Ireland. There, the audience moved through rooms, up an elaborate staircase, traversing three different floors, culminating in a grand octagonal space. The main issue in bringing the show to New York was finding a venue in which the show could work. The Irish Arts Center wanted to be involved from the very start, though I did not think it would work in their space. After many creative meetings and a crucial pre-preproduction week in the actual space, I agreed to take the risk and transfer the work to a black box.

I began to think of What We Hold in New York as What We Hold 2.0. Once I committed to reconfiguring the show to the Irish Arts Center’s black box setting, there were many things that needed attention. Rethinking the audiences’ journey through the space was paramount to retaining the intimacy of each of the four scenes/dance encounters that define the show. We also had to strike the balance of space to audience capacity and came up with 50 people per show as the sweet spot for New York. In Dublin, the audience was limited to 30 people, so adding another 20 felt like a huge shift. This space and audience calculation also determined a few choreographic changes. For instance, scene one would only be performed by one man facing two mirrors, as opposed to two men facing a mirror each, which was the case in Dublin. We also had to double one of row of chairs in the table room to accommodate 50 people.

Another issue we had was to was rethink the sound sculpture’s place and purpose. In Dublin, the sculpture hung through the grand staircase which the audience walked up between the first and second scenes. It was very much a sonic introduction to the oral histories which our composer Ryan C. Seaton embedded in the score. In Dublin, the sculpture existed as an encounter on its own without any performance. Deciding to hang the sculpture horizontally through the space allowed me to envisage an additional image/solo for Colin Dunne, a new member of the cast. It also helped the audience’s journey from scene one to two.

Jean Butler and several cast members onstage during the U.S. premiere of What We Hold. Photo by Nir Arieli

NEA: Once you reconfigured What We Hold spacing for the U.S. stage, what were the next steps in the production development process?

BUTLER: The casting for New York happened simultaneously with the spatial environment of the piece in Irish Arts Center. The cast included three new cast members, Colin Dunne, James Greenan (who took on the first scene/solo), and Kaitlyn Sardin, who accompanied myself and original cast member Maren Shanks on the table scene. I also made sure I had enough time to work with all the new cast members on their roles before we all met in New York to put the show together—which we did in 14 days! The new solos and duets were drafted into place in October 2023, which was an utter godsend.

Lighting was key to distinguish different spaces and create clear pathways for the audience to traverse. Stephen Dodd, our lighting designer, had to design a complete re-light! We also had to have new costumes made by the incredible Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung for the cast. Even with all the restaging, casting, and designing, the show in New York retained all of my original intentions for the work. It is so rare to have the opportunity to rework a show and then get to perform it for 34 shows. I learned so much about the work and myself throughout this process. It was a daunting and exciting and ultimately a testament to everyone involved for making it all work.

NEA: What do you hope audiences walk away with after viewing the production?

BUTLER: I think everyone’s experience of the work will be unique to their perception and expectation of what Irish dance is and can do. From the very first scene, the show declares that this will be something different to anything that has gone before, and it holds that line until the very end. My ultimate hope in making the show was that the incredibly talented and diverse cast were visible in all their unique, idiosyncratic ways of being and moving. How can we, as a group of Irish dancers with all our individual and collective history, be most seen, present, and alive to the moment?

You can watch a trailer of the U.S. premiere of What We Hold below!