Grant Spotlight: Motus Theater

Motus Theater TRANSformative Stories project strategist & monologist David Breña (left) performs his autobiographical monologue during the world premiere of TRANSformative Stories. Motus Theater Artistic Executive Director & Founder Kirsten Wilson (right) on stage in Motus Playback Improv Theater. Photos courtesy of Motus Theater

In 2004, Kirsten Wilson moved to Boulder, Colorado, from New York City to pursue an MFA in Contemporary Theater at Naropa University. While working toward her degree, she became involved in antiracism and social justice work, amid a series of hate crimes targeting college student leaders of color. Reflecting on a past community leader gathering, Wilson said, “If we don’t know the true history of a problem, it is hard to develop strategies that skillfully address that problem at the root. I decided to use my acumen as a multimedia contemporary theater artist to help people understand the history of the community.”

In 2009, Wilson’s performance piece Rocks Karma Arrows (RKA), which examines Boulder history through the perspectives of race and class, premiered during the Boulder Sesquicentennial, attracting over 1,000 attendees and launching community dialogue that led to local policy changes. Building on this momentum, she founded and became the artistic director of Motus Theater in 2011. “Our mission is to create original theater to facilitate dialogue on critical issues of our time,” said Wilson.

In January 2023, Motus Theater received an Arts Endowment grant to support the work of the TRANSformative Stories project that included a 20-week autobiographical monologue workshop and touring premiere, written and performed by transgender leaders.

Wilson and project strategist David Breña spoke with us via e-mail about the ways in which theater can serve as an effective storytelling vehicle, the collaborative process in developing the TRANSformative Stories monologues, and the importance of LGBTQI+ representation in the performing arts sector.

You can watch a TRANSformative Stories monologue by Raye Watson (they/them) below!

NEA: Can you share what your organization does?

KIRSTEN WILSON: Motus continues to present multimedia history performances exploring U.S. history through the lens of race and class. By building on my thirty years in teaching the autobiographical monologue form at universities and privately, Motus Theater’s specialty became collaborating with leaders on the frontlines of violence and oppression in the United States, to develop artfully crafted autobiographical monologues. The monologue projects aim to disrupt dehumanizing narratives, lift up the humanity of monologists, and shed light on the root causes of injustice. Motus features monologists sharing their stories center stage as the protagonists in the American drama and weaves each story with music to help the audience hold the courage, power, and beauty within each story. Motus currently has three touring monologue projects.

In TRANSformative Stories, transgender and nonbinary leaders present artfully crafted personal stories about their hopes, dreams, and experiences of negotiating oppression and liberation. Motus’ UndocuAmerica project aims to interrupt the dehumanizing portrayals of immigrants so that regardless of your perspective on what immigration policy should be, people know the real lives at stake. Motus’ JustUs project supports community leaders who are impacted by carceral systems to share artfully crafted autobiographical monologues that expose the devastating impact of the criminal legal system and inspire action toward a vision of true justice.

In special UndocuAmerica, JustUs, and TRANSformative Stories performances, Motus invites leaders in the criminal legal system, education, politics, business, and religion—whose work impacts transgender and nonbinary communities, immigrants, and people who experience(d) incarceration to co-read the monologists’ stories. These unique co-read performances expand the reach of the projects across sectors, further supporting dialogue around people’s lives and narratives that are too often pushed to the margins.

NEA: Why is theater an effective vehicle for community advancement and reflection?

WILSON: Storytelling is at the heart of what makes us human. The greater the variety of stories that people in our community and country hold closely and understand, the greater possibility we can honor the complex truth of what it means to be human for ourselves, as well as understand actions we might take to have a stronger and healthier community and country. Not knowing the variety of human experiences that make up our community—authoritative stories of directly impacted people that are rarely seen on our stages and in media—not only reduces our own experience of possibilities for our individual liberation, but it can cause us to hold values and create policies that limit and oppress others. The U.S. Declaration of Independence has that beautiful opening, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed, by their Creator, with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” But if you don’t understand the heart, joys, challenges, and fears of your fellow human beings in this country, it is easy not to understand how together we can honor each other and support each other’s rights, equality, life, liberty, and happiness. Theater holds expansive possibilities for expanding perceptions and shining a spotlight on the beauty and humanity of people who might be pushed to the side of the community and country’s narrative.

DAVID BREÑA: You could extract stories from people who are marginalized to try to change the narrative, but that's not what Motus chooses to do. So at the heart of a Motus story, there is a real person, there is real impact.

Motus Theater JustUs League monologists on stage at the Boulder County premiere of the JustUs project. Front: Cierra Brock. Back, from left to right: Dereck Bell, Juaquin Mobley, Daniel Guillory, and Astro Allison. Photo by Michael Ensminger, courtesy of Motus Theater

NEA: Can you give us a snapshot of what the TRANSformative Stories project entails? What are the goals? Can you also describe the selection process for the monologists?

BREÑA: The goal is to generate understanding about trans and non-binary experiences in a climate that urgently needs that understanding. I think this is crucial to where we are as a society today. The political and social landscape we see, in terms of policies regarding trans and non-binary people, demonstrates a clear lack of knowledge and ignorance about trans life and experiences. That lack of understanding is leading people toward hatred and harmful and oppressive policies. Motus’ TRANSformative Stories monologues resist the false narratives about us. We resist by speaking our own truths, claiming our own space, and reclaiming our own narratives about trans and non-binary experiences. We are sharing our true lives rather than being covered over by false narratives of who we are. So ultimately the monologues [enable us to] elucidate, illuminate, and share ourselves with the world.

To select people, we first did outreach through multiple organizations at a local, regional, and national level that work with trans and queer non-binary communities. We made sure we were talking to organizations that work with BIPOC queer and trans people so we had a good representation of different experiences in our communities. We wanted to ensure that there was a diversity of experiences within our trans community in terms of race, gender identity, age, and sexual orientation. Plus we were looking for people that are leaders because the political and social landscape right now in our country can be very aggressive and even violent. So we needed monologists who were interested in courageously sharing their hearts on stages within this volatile climate.

NEA: Can you tell us more about the process of developing these autobiographical monologues? How do you ensure that the stories are both artfully crafted and authentically representative of the monologists' experiences?

BREÑA: There was also a component in the beginning of each workshop, in which Kirsten supported us in sharing with each other how we care for ourselves, and then we would do exercises to help us rest more deeply in our bodies. We did these exercises in a repeating ritual process that made the experience a sacred space. As a therapist and artist, I felt the process was guided with a lot of care and support and in a very trauma-informed way. It really helped me put together the narrative of who I am as a trans person, which I don't think I had done before. And that was really a beautiful gift of the monologue process, as I am still going through some of

these stages in my journey, and it was very powerful. Because of the art of the collaborative process, it's not extractive or exploitative, but it's rather honoring, and respecting, and representing people's truths.

WILSON: I think of collaborating on monologues like quilting. Each writing a person develops in the monologue workshop is like a beautiful detailed patch that could be part of a quilt. As they write each narrative, I see the patterns emerging. Once the monologist chooses what story they want to develop for the stage, I reflect with them on their writings in which their chosen narrative appears in larger pieces or fragments, and then I support making that narrative more visible and weaving the complex and detailed threads of that narrative into a whole tapestry.

My style of collaboration resonates with my studies of the Japanese dance theater form of Butoh. Like a Butoh practitioner, I must first strive to be an empty vessel. I try to listen so deeply to the words of another person, that I am a container simply holding and repeating their words. If I can empty myself out and just be a vessel that temporarily reflects their writings and stories back to them, then I can function as a mirror in which they can clearly see and hear themselves through their own words. Once they recognize themselves in their own story as completely as possible, and it says exactly what they want it to say, the monologue is ready for the stage.

Grammy Award-winning and internationally renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma (right) hugs Motus Theater’s Salsa Lotería monologist, Ana Casas, after performing a musical response to Casas’ monologue. Former Boulder County District Attorney Stan Garnett, left, co-read Casas’ autobiographical monologue about the deportation of her brother. Photo by Jill Kaplan, courtesy of Motus Theater

NEA: Each monologue also includes music. How do the musical elements enhance storytelling within the performances?

BREÑA: I think the musical responses mainly provide support and space for both the audience and the monologists to reflect and integrate the story and then to come back to themselves. The stories can be very moving, with parts that are heartbreaking, parts that are joyful. The music helps the audience and monologists hold all of that and process it in their nervous system. It’s not just silence or a minute of space, it's a gift for the audience, a gift for the monologist to respect, to give closure, to give space to transition, and to come back and into a more peaceful state.

I have to say that my favorite part of how Motus uses music is the way Kirsten works with musicians to develop an underscore for the story. I really feel it enhances the monologue and gives the monologist a bridge from which they can express a wider range of emotions as they share their story.

NEA: Can you share any stories that highlight the impact of TRANSformative Stories?

BREÑA: I have had several parents come to me, tearing up, and saying it was really helpful to see this performance because their kids are just starting to transition or are starting to go to therapy or starting to figure out what it means for them to be trans. It was helpful for them, in their process as parents, and it was also impactful for me to receive this feedback from parents because, in addition to being an artist, I work professionally as a therapist with a lot of trans youth. And most of these youth haven't had that level of acceptance from their parents. It was healing for me to hear from parents that are supporting their kids.

As an actor, the TRANSformative Stories project has been tremendously impactful because it has allowed me to return to what I love. I think part of the reason why I didn't go into acting as a full-time profession after I graduated from a theater program has a lot to do with not fitting the gender and racial expectations of the acting industry. And although I am not performing in the way I was trained, in that I'm not acting in someone else's story, it has been healing and powerful to be back on stage and be validated for actually the very things that once were the biggest barriers to my participation in this industry—for being a trans queer immigrant and for being exactly who I am.

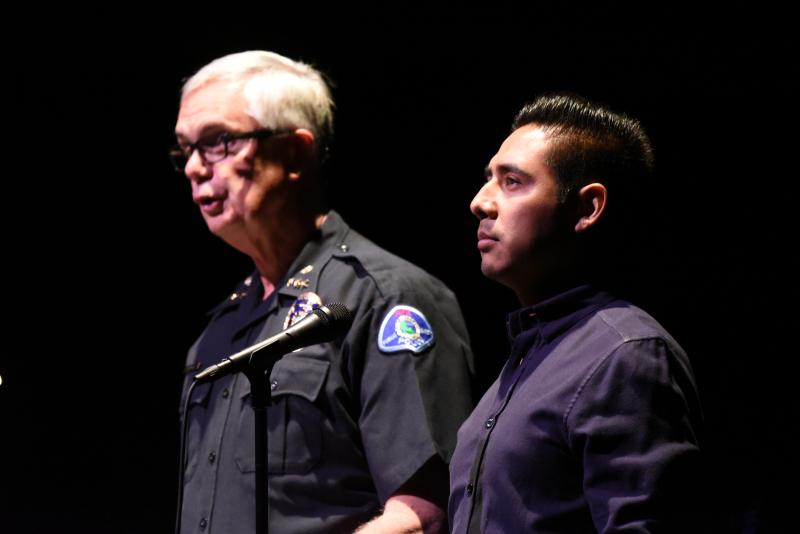

Longmont Police Chief Mike Butler (left) stands on stage with Motus Theater’s Do You Know Who I Am? monologist Hugo Juarez (right) and co-reads Juarez’s autobiographical monologue about his experience of growing up undocumented in “Law Enforcement Leaders read Do You Know Who I Am?” Photo by Michael Ensminger, courtesy of Motus Theater

NEA: What are other ways in which Motus engages with the community?

WILSON: We bring Motus performances to community organizations, civic organizations, and schools that are striving to create safer and more equitable spaces that allow all their members to grow. In addition to staged monologue performances and multimedia history performances, Motus also features Playback Improv Theater Company, a group of culturally competent artists who can enact the stories of audience members on the spot.

Motus doesn’t have the resources to develop autobiographical monologues with everyone in our community. But these improv performances allow us to bridge part of that gap by providing a form that supports community members to have their stories enacted by a group of professional improv artists—complete with musical underscore—so we can learn from each other’s human experience.

Motus Theater JustUs League monologists on stage in front of 1,600 people during the world premiere of the JustUs project at the National Association of Community and Restorative Justice. Front: Juaquin Mobley. Back, from left to right: Daniel Guillory, Dereck Bell, Astro Allison, Brian Lynch, Cierra Brock, and Brandon Wainright. Photo by Rick Villarreal, courtesy of Motus Theater

NEA: Complete this sentence. LGBTQI+ representation in the performing arts sector matters because…

BREÑA: We are all missing out on all these stories. And trans people, in particular, are missing out on seeing themselves reflected alive and in the world. And if people don't know our stories, then they don't know that we're also human. It's easy to hate someone you don't know. And some people will never change their views. I think representation matters because it really creates understanding.

WILSON: Everyone’s experience of their sexuality and gender is reduced when only straight and approved gender narratives are allowed. And we need to talk, not only about LGBTQI+, and specifically trans and nonbinary representation in the theater, but also about the authorship and authenticity of that representation.

Historically, most dominant cultural performances, films, and TV shows featured LGBTQI+ characters either as sidekicks or as the antagonists in the drama, and LGBTQI+ people of color were rarely seen at all, and if they were part of the roles, they were the antagonists or a tragic figure. It is essential that we have a diverse range of LGBTQI+ artists represented as writers, directors, producers, as well as actors, and that we produce work in which LGBTQI+ people are the protagonists in the drama. It was through courageous LGBTQI+ arts leaders in theater, film, and television who came out of the closet and shared their humanity, that society slowly shifted so that all of us, regardless of sexual orientation and gender, can have more freedom to be ourselves.