Art Out Loud

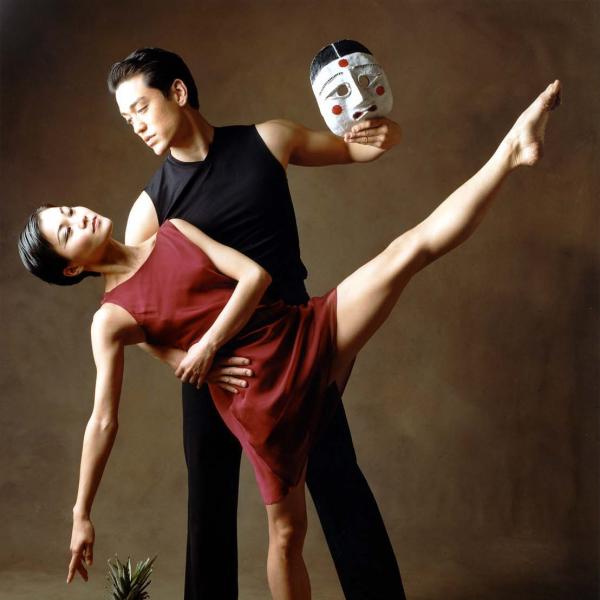

Photo by Lisa Scheer

If you live or work in Washington, DC, chances are you pass by at least one work of public art every day. It could be the mural that replaced graffiti on a nearly 1,000-foot-long wall in Northeast's Edgewood community or the two sculptures at 5th and K Northwest that adorn the center of a neighborhood undergoing urban revitalization. While these are classic examples of visual art, public art can be in any medium as long as it has been designed and executed with the specific intention of being installed in a public space. So the abandoned call boxes in neighborhoods around DC that have been refurbished and painted, the bike racks designed by DC artists, the decorated jersey barriers protecting a government office -- all public art.

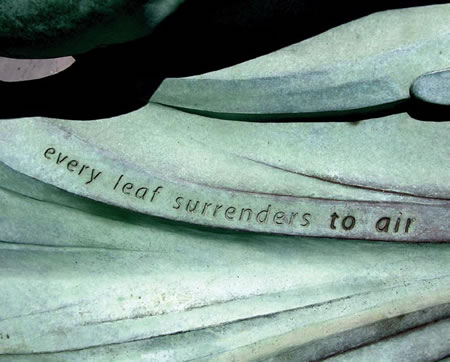

The poet E. Ethelbert Miller contributed a poem, which was inscribed on the sculpture: every leaf surrenders to air / we dance / we flutter / we touch the earth. |

The landscape of public art in America over the past 40 years has changed and grown substantially. "I went to graduate school in the late seventies and in those days I could literally count the number of public commissions there were available in the United States in any one year," said DC-based artist Lisa Scheer. "Now, every single little 'burb seems to be doing it." This growth can be traced in part to federal programs, such as the NEA's Art in Public Places program, which from 1967-1995 funded the creation of more than 700 works. But in addition to programs with national reach, organizations also work on the regional, state, and local levels to develop projects that make public art an integral part of communities. In Washington, DC, the Commission on the Arts and Humanities (DCCAH) leads the city's efforts to purchase, commission, and install public art through its program DC Creates Public Art.

Established in 1986, DC Creates is part of legislation that allocates up to one percent of the city's adjusted capital budget for commissioning and acquiring artwork. Over the past 30 years DCCAH has installed more than 100 commissioned projects and collected more than 2,000 works of art from DC artists for its Art Bank Collection, which is exhibited in dozens of public buildings throughout the city.

With large numbers of people living and working in Washington, DC, as well as visiting its museums and monuments, DCCAH has targeted DC's metro stations as important sites for public art, commissioning works at 16 of the stations. Lisa Scheer, one of the artists to benefit from these commissions, has spent her career teaching and working in the DC area. Her sculptures can be seen throughout the city, from office buildings to the Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport. "Neighborhoods are certainly one sort of way of bringing artworks to where people live," said Scheer, "but the other idea is to integrate artworks with architecture in civic areas where people travel, go through, and move around, come into contact, transportation being an obvious one."

In 2004 Scheer answered an open call issued by DCCAH outlining the project details for the Petworth metro station public artwork, and was awarded the commission. Petworth, an urban enclave in DC's northwest quadrant has -- like many other neighborhoods in DC -- undergone urban revitalization in recent years, a change referenced in Scheer's community sculpture.

Installed at the Petworth Metro station in November 2007, New Leaf is representative of her work -- primarily large-scale abstract sculptures constructed out of metal and fabricated sheet metal. Scheer said, "My goal is to have a mixture of really interesting references, oftentimes stemming from the sort of program or the site in which I'm installing the work. The piece at Petworth is a sort of abstracted form, but it also looks a tremendous amount like a leaf, or something very organic and growing, and I do mean to do that because I mean to evoke metaphors of growth and change and seasonal time shifts."

When creating a public artwork, Scheer asks four questions related to the community where the object will be installed: Who's there? Why are they there? What are they doing? How can my art speak to that? "When I make an artwork in my studio, it can be shown in a gallery, it can exist in someone's home, it can exist on any wall. But when I'm doing a commission, it's made to live in a certain place."

Public art is unique not only in its reflection of a community, but also in the reaction it elicits from that community. Liesel Fenner, public art program manager for Americans for the Arts, explained, "With public art the community becomes the owners of the art work -- they protect it and consider it a part of their place -- and because of this the art becomes more understood. For many people public art is their first introduction to art and can serve as an important tool in creating awareness of what art is and can be."

Beyond providing this initial introduction, public art can also serve as a valuable tool for broadening the public's view of art. This is particularly true of temporary public art where, because the pieces are not permanent, artists have more room to experiment and challenge their audiences. According to Dickerson, such public art "can often have a powerful impact on a place because of the way that projects are able to 'push the envelope.'"

In January 2009 DCCAH issued a five-year Public Art Master Plan, calling for more temporary and permanent public art works and outlining the ways public art can be integrated into the city's future: weaving public art into the city's civic and community fabric, building a green and sustainable city, and stimulating the creative economy.

But beyond these goals, public art has a very simple yet valuable result -- it helps creates communities where people want to live. "There's something to be said about coming across an artwork every day," said Scheer. "When we go to a museum, we set our minds to a certain way of thinking, and it's about art. We're assuming that activity. Whereas when it's in your daily environment, the artwork has to meet you where you're at, rather than the other way around, and I think that's pretty cool."