Rebuilt Through Art

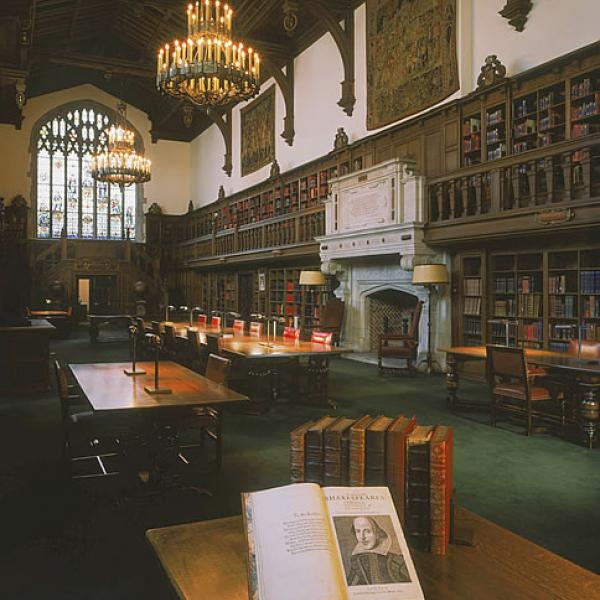

Photo courtesy of Studio Theatre

"Twenty-five years ago, the streets of Logan Circle were littered with condoms and hypodermic needles," said Washington, DC theater director and arts entrepreneur Joy Zinoman with a wry laugh. "There were lots of robberies and people peeing on the doors and city survival." Fast forward to 2010 -- the area has a new face and identity. "It's this hip, chic, and diverse neighborhood," she continued. "There's a Whole Foods nearby and new residential condos. It's an extraordinary area which is still at a human scale and has mixed use -- shops, restaurants, bars, places to live."

The reason for such a dramatic urban transformation? "It all swirls around the Studio Theatre," said Zinoman, the company's founding artistic director. "The theater is the anchor."

One of the country's most respected regional theaters, the Studio currently boasts four performance spaces with more than 800 seats total, spread across three historic, custom-renovated buildings on P Street in Northwest Washington, DC. Zinoman's theater specializes in cutting-edge, contemporary works and continues to earn a steady stream of Helen Hayes Awards for outstanding theater in the Washington area; 2009 also saw Zinoman recognized for Visionary Leadership in the Arts by the Mayor's Arts Awards. And while the theater's artistic accomplishments are widely heralded, its transformative effects on the Logan Circle neighborhood demonstrate a different sort of accomplishment -- realizing arts organizations' potential as engines of social and economic progress.

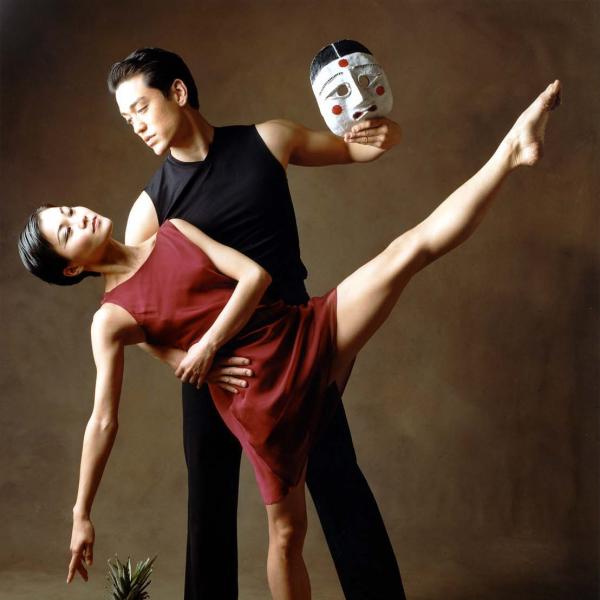

(l to r) Raushanah Simmons and Yaegel T. Welch in the Studio Theatre's 2010 production of In The Red and Brown Water by Tarell Alvin McCraney. Photo by Carol Pratt |

The Studio Theatre's story began when Zinoman opened a Washington-based acting conservatory in 1975 and a fledgling theater company three years later. Having come to the nation's capital by way of Chicago, a city with a powerful small theater movement, she had a specific aesthetic in mind for her architectural canvas. "In Chicago, it was all about theaters in found industrial spaces," she commented. "When I was in the process of founding a theater in DC, I too went to look for industrial spaces, spaces that had history and architectural distinction from a past life that could have an adaptive use."

Though Washington houses little industry per se, Zinoman did discover what she was looking for in a series of historical 1910 buildings in Logan Circle. "There were these amazing automobile showrooms with giant elevators for moving cars up and down," she said. "They were built in Italian Renaissance-revival-warehouse style with big windows on the ground floor and columns wide enough to put theaters in." Given the destitute neighborhood, ravaged by the riots of 1968, and its subsequent rock-bottom rents, one of the warehouses soon became home to the Studio.

From the theater's birth, Zinoman's eyes were on the future. "The history in New York was that artists would move to ever more marginal neighborhoods and be pushed out when they could no longer afford to live there," she said. "We bought this building so that wouldn't happen. First, we raised money and put a million-dollar theater in a building we didn't own. That was an insane thing to do. But then we bought the building when it became available, and then the two next to it."

Zinoman and her team took their time raising funds to make those purchases and gradually expand the theater over decades, launching a series of smaller, sequenced capital campaigns to achieve their goals. "From a fundraising standpoint, it's harder in Washington than in a theater city that has a big industrial base, or old families that have been there for generations," she said. "The Pillsburys in Minneapolis, for example. Washington does not have that corporate base."

Julia Nixon and Max Talisman in the Studio Theatre 2006 production of Caroline, or Change by Tony Kushner. Photo by Scott Suchman |

Building on the continued success of their modest efforts in the five-to-fifteen-thousand-dollar range, the Studio steadily grew its savings accounts, as well as its cultural and physical footprints. "First, acting students came for our conservatory classes, and then people started to hear about it -- and come, and come, and come," she said. "It's remarkable. After the riots, everything was boarded up. Business had left and people were very negative about the possibility of a theater audience coming here."

Now, any given night sees theater-goers flocking to the neighborhood and patronizing a vibrant nightlife scene. "That's a lot of people who want to live nearby and who need bars and restaurants," Zinoman said.

Gil Thompson, the Studio Theatre's resident sound designer and a Helen Hayes award winner, lives on Q Street, half a mile from the theater. He witnessed the neighborhood's transformation first-hand. "I've been here since 1978 and have worked on 23 seasons at the Studio, since the fall of 1987," he said. "One year before the Whole Foods came along, on one block of P Street between 14th and 15th Streets, I was mugged three times in six months, all coming and going to the Studio Theatre. I can't begin to emphasize how things have changed since the Whole Foods, the bistros and restaurants, and the new condos have come along, all led by the Studio originally.

"One of those times I was mugged, I was threatened very fiercely with knives and I literally thought I was about to die," Thompson recalled. "Now I've walked home along that same block countless times late at night and there is always a lot of nightlife and activity."

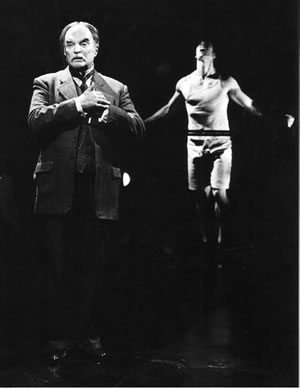

Ted van Greithuysen (foreground) in the Studio Theatre's 2002 production of The Invention of Love by Tom Stoppard. Photo by Carol Pratt |

Both Thompson and Zinoman readily acknowledge the controversies and stratified opinions surrounding the topic of gentrification, yet in the Studio's case, Zinoman sees it as a clear turn for the better. "Some people look at Logan Circle and say, 'It's all filled with yuppies now,'" she said. "I see it another way. Sam's Pawnbrokers is still here. There's still subsidized housing. The neighborhood has a high level of halfway houses and services for people in need. I think it's one of the most diverse neighborhoods in Washington. We engaged with our neighbors early on and it was always important for us to stay that way." In addition to the 11 shows it stages each year, the Studio regularly makes its spaces available for meetings by community organizations such as the Logan Circle Community Association, Food For Friends, and the Whitman Walker Clinic.

For Zinoman, preserving local diversity is key, as is nurturing a symbiotic relationship with the neighborhood. "Integrating arts institutions into the places they are is essential," she said. "There are theaters that want to be destinations for tourists or for people traveling to a certain place -- but I really think that all theater is local. No matter where the artists come from, they are still creating work within a specific space and time. And whether it's a hillside in ancient Greece or on 14th and P, theater is defined by being in a place. You can't get away from that, so it's best to embrace it. Great things can come if you do."

One such place-specific benefit is the ability to perform for outstanding local audiences. "Washington, DC has unbelievably sophisticated patrons," she said appreciatively. "Lots of highly educated, young, idealistic people come to this city to work. The Studio has developed a very smart, mixed audience. And that's the best part."

Michael Gallant is a composer, musician, and writer living in San Francisco. He is the founder and CEO of Gallant Music (gallantmusic.com).