Creativity in Collaboration

David Harrington, founder of the Kronos Quartet. Photo by Zoran Orlic

Audiences lucky enough to catch the Kronos Quartet in concert might expect to feel any number of emotions -- excitement at the group's virtuosity, intrigue at the eclectic musical sources they gracefully synthesize, and wonder at the sheer creativity needed to conjure such fabulous music, performance after performance and album after album. They might also experience surprise if they were to learn that the group's creative lifeblood flows not from some unknowable, magical place, but rather from the nexus of rigorous exploration, extensive research, a strong commitment to excellence, and dedication to hard work -- in short, qualities Kronos founder and violinist David Harrington has in spades.

When we spoke with Harrington, he was in Boston, Massachusetts, putting these principles to work to rehearse and perform what he believed to be the world's first piece for electric string quartet and the newly developed electric gamelan. "I've been interested in the compositions of Christine Southworth and the Gamelan Galak Tika ensemble for several years," he said, referring to Kronos' collaborators on the project. "[Music videogame pioneer] Alex Rigopulos and members of the MIT Media Lab have been involved in assembling and imagining these instruments, so we're right at the beginning. It was the perfect opportunity to try something new!"

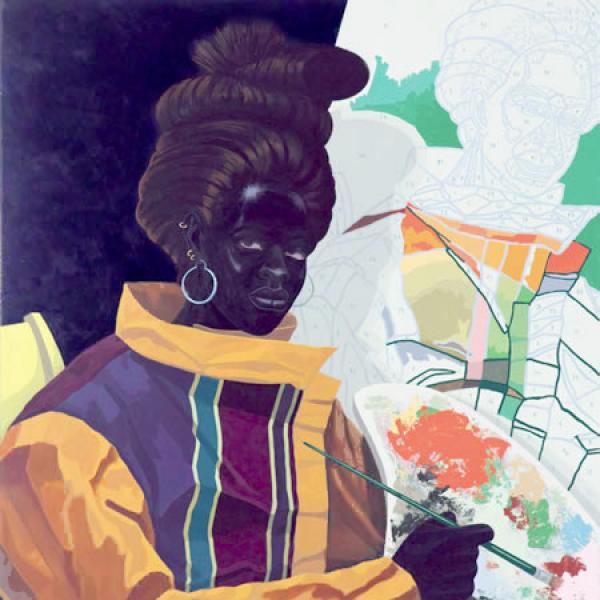

The Kronos Quartet performing George Crumb's Black Angels. |

Harrington founded the Kronos Quartet in 1973 after hearing an adventurous New York quartet performance of George Crumb's Black Angels on the radio. The Vietnam War-themed piece, which featured such eclectic instrumentation as bowed water glasses, gongs, and wild electronic sound effects, resonated deeply with the violinist. "Hearing Black Angels answered an emotional need," he said. "The Vietnam War was still hanging heavily in the air and many young people felt totally helpless. I was lucky because I instantly knew what I had to do -- to play Black Angels. Hence the immediate formation of Kronos."

Over three decades later, Harrington continues to channel an explorer's spirit into the group's work. "I try to know as many of the things that are missing from our world of music as I possibly can," he said. "There have been nearly 700 pieces written for Kronos, but so many things still haven't yet been done. I try to put the thrust of my time into realizing those things that aren't yet part of our work but should be."

Through its more than 45 albums and constant performances around the world, Kronos continues to push the boundaries of what music a classical string quartet is expected to play, primarily using collaborations with composers and musicians of varied backgrounds as its creative fuel.

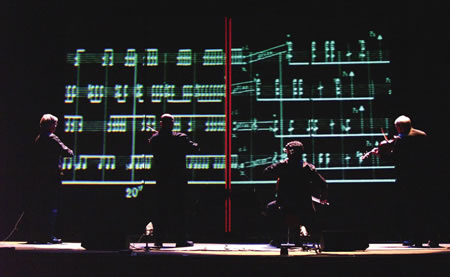

The Kronos Quartet (Harrington, John Sherba, Jeffrey Zeigler, and Hank Dutt) performing during their evening-length multimedia production Visual Music. Photo by Zoran Orlic |

Just as noteworthy as Kronos' collaboration with Southworth and Gamelan Galak Tika is the group's work with artists such as choreographer Merce Cunningham, industrial rock pioneer Nine Inch Nails, composer Philip Glass, and Chinese pipa virtuoso Wu Man. The group's creative partnership with Indian singer Asha Bhosle manifested in a critically acclaimed and Grammy-nominated album entitled You've Stolen My Heart: Songs from R.D. Burman's Bollywood; the group has also worked on such film scores as Requiem for a Dream, Heat, and 21 Grams. And the list goes on.

For Harrington, Kronos' collaborations are equally about musical and human connections. "Terry Riley has been central to Kronos' music for the last 32 years," he said of the minimalist composer who has created 24 pieces for the quartet so far. "He's a very generous musician and his music reflects that generosity. There are very few people in any creative field who can push the world of their art into another place and he still does that. I'm so proud of our work together." Also particularly noteworthy is Kronos' 1994 collaboration with iconic beat poet Allen Ginsburg, who met Harrington after Kronos coaxed a Lincoln Center audience, of which Ginsburg was a member, to sing along with their final tune of the evening. "Kronos was set to do its debut at Carnegie Hall soon thereafter and I had been wondering how we were going to distinguish that moment from all others," said Harrington. "After seeing Allen in the audience that night, we asked him to join us on stage to read his breakthrough poem ["Howl"], and he said yes."

The Kronos Quartet, with Wu Man on pipa, performing Tan Dun's Ghost Opera. Photo by Luis Delgado |

Given his great musical curiosity, and the overwhelming number of genres from which to choose, how does Harrington whittle down the options for potential Kronos collaborators? "A lot of my work is curatorial," he explained. "I'm constantly listening to new things. One of my current explorations is music of the Scottish Diaspora, the way the music has been transmitted through to Nova Scotia and later to places in North Carolina and Jamaica. That's just one example. I spend a lot of time just thinking about people who are involved with music and somehow magnetize me personally. I love the process," he continued. "I've already been in touch with fifteen composers this morning. And that's what I do every day."

Each collaboration Harrington engages in presents unique challenges, sometimes requiring Kronos and its creative partners to bridge significant communication gaps. "The Gamelan ensemble we are currently rehearsing with doesn't work from traditional Western notation the way that we do," he said. "We had to work with Southworth to make sure our playing synced up. They memorize everything and know to repeat a section this many times and then move on." Other challenges the group has faced include performing musical surgery in rehearsal, days or hours before a performance. "Our rehearsals are often about revising a piece directly with the composer so his or her work is realized most fully," he said. "It can be thrilling and scary."

Given such creative risk-taking, it might be reasonable to expect the quartet's many successes to accompany at least a modest amount of failures -- yet Kronos seems to have earned a preternaturally spotless record, continuing to deliver inspired and cohesive performances with every new step outside the proverbial box. The answer? "Research," said David. "I'm anxious to minimize those moments of falling on my face in public. I would do everything possible to not bring something to the stage that didn't feel like it had the entire weight of our past in it. I'm looking for those things that feel very natural as a next step and, for me, that means being aware of what we've done, but being totally open to what we haven't seen yet, and to the immense amount of work we've never had a chance to be part of yet.

"If I find a person or a situation that pulls me in and feels right, I trust that totally. If something doesn't feel right, though, I'm going to get out of it before it hits the stage."

Inherent in Harrington's performance philosophy is the desire for constant growth. "I had a wonderful violin teacher, Veda Reynolds, who I had the great fortune to have studied with for 30 years," said Harrington. "The last lesson I ever had with her before she died, the last thing she said to me was, ‘The great thing about music is that it can always be better.' And this was after I had worked on one note with her for three hours!"

"I've tried to internalize that comment and pass it along to other musicians as much as possible," he continued. "That's the musical impetus that keeps us going, that search for something that is deeper than what we're used to, that fluently expresses more of the world that we know -- and worlds we don't know -- through music, and through collaborations with people that inspire us."

An equally important lesson in creativity that Harrington carries with him is the importance of living a vivid, engaged life. "I try to read several newspapers every day, keep my ears open, and stay alert," he described. "You can learn a lot by walking down the street and just listening to people, watching children, watching very old people. There are so many lessons to learn and life is very, very short. You want to use your time to its best advantage."