Traditionally Innovative

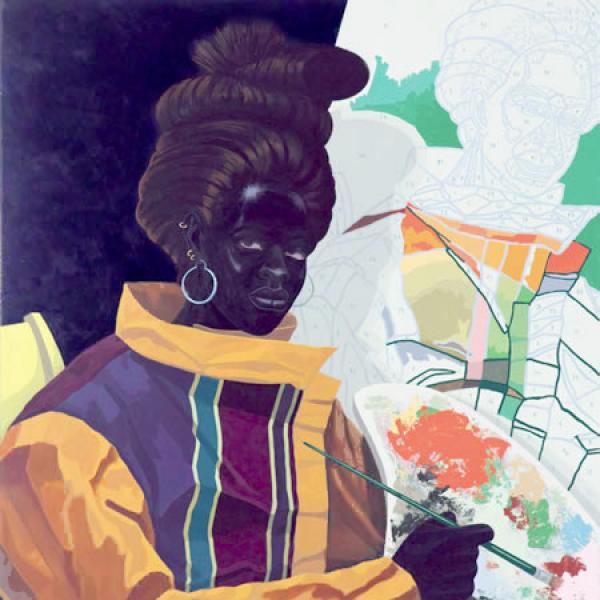

Wasco weaver Pat Courtney Gold presents her baskets at the 2007 NEA National Heritage Fellowships concert. Photo by Michael G. Stewart

The Wasco Nation of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, Oregon, has a legend about how their baskets got their distinctive designs. As basketweaver Pat Courtney Gold tells it, "A girl wanted to learn how to weave, so she sat under a cedar tree. She was making a basket but didn't know what kind of design to put on it. The tree told her, ‘Look around and you will see images.' She looked around and the first thing she saw was mountains. So her mountain design became triangles -- geometric triangles -- all in a row. She showed that to the cedar tree and he said, ‘That's what I want you to do.' As we listen to this legend, it helps us open up our eyes and go out in nature and see things that you think would be good for a basket. That's one way that we get our inspiration."

Nature and the world around her continue to influence Gold, a member of the tribe whose full-turn twine technique and geometric designs not only draw from centuries-old Wasco baskets but also reflect her current life and that of her tribe. But Gold didn't grow up with the tradition -- she had to learn it from scratch.

The only access Gold, as a child, had to her tribe's basketweaving traditions was through the Maryhill Museum of Art on the Columbia River, a three-hour drive from her home. Gold's mother would lead her and her sister to the museum's basement and the collection of Wasco baskets. "I remember her taking us there and pointing at them and I could hear her voice change. She really had pride in her voice when she said, ‘Our people made these baskets.' When I looked at them I knew my grandmother and mother didn't make baskets and I really thought that we would never see anyone making them again…. It never dawned on me that I would grow up one day and be weaving baskets."

A Wasco sally bag made by Pat Courtney Gold featuring colored horses. Image courtesy of the artist |

Gold didn't take up basketweaving until later in life after she was established in a career as a mathematician. Her sister called with the news that there was an elder who was concerned that the Wasco basketmaking tradition would be lost and had found other elders who knew some of the weaving traditions and were willing to teach what they knew. "Two elders knew part of Wasco weaving, some knew how to start, some knew how to do designs, quite a few didn't know how to end the basket, none of them knew what the traditional materials were." Gold spent the next eight months meeting with the elders to put the pieces together and learn full-turn twine weaving, the technique used to make Wasco baskets' distinctive designs. She eventually left her career as a mathematician to devote her life to the tradition of Wasco weaving and ensure its passage on to the next generation and all those interested in weaving.

In addition to learning the mechanics of weaving, Gold recognized that an important part of carrying on this tradition was identifying the original plant fibers used. Working with tribal elders, she and her sister gradually identified some of the plants, which were often threatened by construction or marked as invasive by federal and state agencies. As a result, Gold helped to found the Northwest Native American Basketweavers Association, which educates state agencies about the importance of protecting these natural plants and their habitats. Gold also integrates instruction in identifying these plants into her classes, passing along to the next generation the importance of being "stewards and caregivers to the earth so we'll continue to have these plant fibers and the clean water and clean air."

For Gold, immersing herself in the history of Wasco weaving also has been an important part of her craft. "In order to appreciate Wasco baskets you really have to understand the culture, otherwise the designs won't mean anything to you. If you look at a basket with a condor -- a lot of people look at it and think it's a butterfly. But if a Wasco person who knows their culture looks at it, they know immediately it's a condor."

One of Gold's weavings, made of cattail, cedar, tule, and yucca. Image courtesy of the artist |

As part of her own learning, Gold traveled extensively to see different types of Wasco baskets and learn more about the materials used. She discovered that every Wasco basket was unique -- no two designs were exactly the same -- but the designs also reflected changes in the tribe. For instance, boat and canoe designs altered over time and when horses were introduced to the tribe they began showing up in designs.

Materials and colors also reflected the changing times. Many early baskets were made from pine; in the late-1800s, basketmakers began using cotton string left over from harvesting hops. Historically, baskets had a gold-brown background with black or dark purple for the design work. With the introduction of different dyes, new colors were incorporated. Gold explains that since the weavers were living on the reservation it was difficult to find the traditional materials, so they had to adapt. "I can see changes throughout history and I realize cultures are not static, they are dynamic. So when new things are introduced, new fibers, man-made fibers, new things that are now in your environment, you can incorporate them, because that reflects who you are at this time in history."

What distinguishes Gold's baskets from those woven by her ancestors is her distinctive use of contemporary iconography alongside traditional designs. An image of a condor will appear next to an image of an airplane. Ancestral figures are contrasted with what Gold refers to as her "yuppie images" -- Native-American figures dressed in suits and dresses. "I think it's natural for me to weave what I call ‘the yuppie couple,'" says Gold, "because we now have young people going to college and they're lawyers and they're in business and they dress differently and the men wear suits and the women wear dresses and I think, well, that's part of my culture and I'm portraying it on my basket."

Another sally bag by Gold, this one featuring flying geese. Image courtesy of the artist |

Gold's baskets also provide an outlet for commentary on issues important to her, such as the health of the Columbia River. The river and the fish that lived in it were historically an important part of her tribe's welfare, as reflected in the basket's designs. Gold continues this tradition of portraying the river's fish on her baskets, but with a different angle. "Instead of talking about the radioactive pollution in the Columbia River, I will portray it in my sturgeon. The sturgeon live in the Columbia River so I have the sturgeon on my baskets, but I always have one deformed sturgeon. That sturgeon is unfortunately deformed because it's living in the Columbia River. Visually, someone can see what I'm stating so I don't have to write a page about all the pollution -- it's right there for them to see."

Five years ago, Gold and a fellow artist, Suzanna Santos, developed a two-week summer program for Native teens, providing hands-on instruction in Native- American art and culture, an opportunity not available to Gold in her youth. While the students are encouraged to create their own images, Gold still instills in them knowledge of the history of Wasco baskets. "When I teach I really stress the history, especially the history along the Columbia River. We are now going on three generations of people who have not lived along the Columbia River and they do not understand how important the river was, and salmon was, and the trade was, and how important the baskets were to our culture."

In 2007, Pat Courtney Gold was recognized with an NEA National Heritage Fellowship for her dedication to carrying on the traditions of Wasco weaving. Gold emphasizes that any recognitions she has received over her career are due in great part to the support and knowledge passed on to her by her elders. But it is Gold who has managed to take this art form and balance its traditional elements with a vision of the modern world, creating a collection of Wasco baskets that reflect the Wasco tribe as it is today.