Grounded in the Old

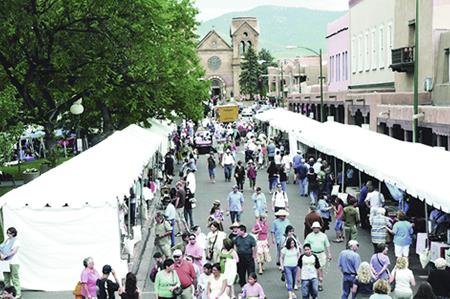

Crowds roam through the Spanish Market in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Photo by Gene Peach

"If you can't go to Market and be a culture broker, don't go to Market." That's NEA National Heritage Fellow Charles Carrillo's advice to the artists who participate each year in Santa Fe's Spanish Market, one of the oldest and most renowned festivals of traditional arts and crafts in the U.S. The market, which also features cuisine and performing arts, shows off the region's master Hispano (as those of Spanish descent are called in the Southwest) artisans, from furniture makers to weavers, and embroiderers to painters. All are fluent in the art traditions Spanish settlers brought with them to the New World starting in the 15th century.

Spanish Market was founded in 1925 by writer Mary Austin and writer-artist Frank Applegate as a way to keep Hispano artists from migrating out of state for ranching or mining jobs in Colorado and elsewhere. Just a year earlier, Austin and Applegate had founded the Spanish Colonial Arts Society -- which now has museum holdings numbering 3,700 objects -- to help preserve the physical artifacts of New Mexico's Hispano heritage. For centuries, the Catholic Church had been the region's chief patron of the arts. As the state's small parishes closed, not only were many artworks lost to outside hands, but local artisans also lost their livelihoods. As Donna Pedace, the society's executive director, explained, "People did not collect Spanish art here in New Mexico. So when [Austin and Applegate] founded the society, they held the very first Spanish Market with 11 artists because they were trying to provide a venue for the artists who were trying to make a living."

The market, which has operated on an annual basis since 1967, continues to be what Pedace calls an "incredible economic force." She noted that many of the roughly 300 artists who participate support their families from Spanish Market sales alone. It's an easy leap to extrapolate the market's positive effects on the regional economy. Referring to the most recent event, which took place on July 30 and 31 of this year, Pedace said, "The city estimates that we had 70,000 visitors. Not all but most of those stay in hotels, they eat in local restaurants, they certainly purchase the art, and tax dollars from those purchases benefit the city directly. Many of the visitors who come to market stay in the state anywhere from three to ten days so they're not just here in Santa Fe but they visit other parts of New Mexico."

According to Loie Fecteau, executive director of the state arts agency, cultural tourism is a powerful force in New Mexico. "Tourism is either usually the number two employer or number three employer behind defense spending and government employment statewide…. Aside from the natural beauty of New Mexico, one of the main reasons that people come [here] is because of our unique arts and culture. It's really just part of the fabric of our whole being."

2006 National Heritage Fellow Charles Carrillo. Photo by Tom Pich |

The economic benefit, however, is secondary to the market's primary goal to promote the vibrancy of centuries-old traditions -- a mission wholeheartedly embraced by vendors. "[Artists] are there with their families. They love to talk to the visitor about their art, explain the traditional methods and materials that they use to create it, explain the heritage behind it, the culture that the art comes from it," said Pedace.

To ensure the Spanish Market's cultural legitimacy, artists undergo not just a rigorous jurying process, but must also prove that they reside in New Mexico or southern Colorado, and are at least one-quarter Hispano heritage.

Fecteau noted that this rigor leads to an authenticity that makes the showcase unique. "I think one of the most amazing things about the Spanish Market is that it is so authentic, and you really do get to taste history -- whether that's through the art itself and also meeting the artist. But there'll be Hispanic music playing for free on the plaza and wonderful food…. [A] lot of Spanish people who live in New Mexico attend this festival, and I think a lot of that has to do with authenticity."

She added that the Spanish Market showcases the ingenuity of the early settlers. "We were a Spanish colony, and a lot of these artistic traditions were introduced into New Mexico in the 17th century. However, a lot of the materials weren't available, and so sometimes New Mexico Hispano art is sometimes referred to as 'poor man's art,' but I think it's more aptly referred to as the artwork of ingenuity. Folks became very clever at using whatever resources were on hand. For example, straw appliqué was done because they didn't have access to gold or gold leaf."

Carrillo agreed that authenticity is a market hallmark, noting that anyone with talent can make these crafts, but not everyone can lay legitimate claim to these inherited traditions. He added that the Spanish Market provides opportunities for a richer interaction with the Hispano Diaspora.

"We have very few chances for people who come here to interact directly with Hispanos unless they're interacting with them in the service industry," he noted. "We get to interact with them [at Spanish Market] one-to-one and become culture brokers. We get to tell them why it's important that these traditions are alive, and we get to talk to them about our culture and our language and our traditions and heritage and all those things."

Carrillo himself has exhibited at the Spanish Market since 1980 when he was both a graduate student in archaeology and a relatively new santero, or maker of traditional wooden statues of Catholic saints. He became intrigued with santos while working on an early 18th-century church site in Abiquiu. "Working as an archaeologist got me interested in the archives. The archives led me to the santos. The santos led me to the kitchen table," he explained.

Carrillo's archaeological work also led to an expansion of the types of crafts eligible for the market. He proved that pottery work, basketry, and bone carving were also brought to the Americas by Old World travelers whereas it had been assumed that those crafts were adapted from Native-American traditions.

2007 National Heritage Fellow Irvin Trujillo. Photo by Tom Pich |

Weaver Irvin Trujillo -- also an NEA National Heritage Fellow -- first sold his own work in his father's Spanish Market booth in the early 1970s. He credits this experience with deepening his own engagement with Hispano culture. "There is a change in the culture from being New Spain to being part of Mexico and then being conquered by the United States and then actually becoming a state. In textiles, each one of those periods changes the aesthetics of the work, and so to know the tradition I have to know the whole history of New Mexico and its influences. So that really interested me to delve into the history. I don't know if I would have done it without the Spanish Market's influence." Trujillo added that he appreciates the market's jury system as it "encourages me to do my best work. I can't slack off."

While many market artists have participated for decades, the Spanish Colonial Arts Society also encourages participation by up-and-coming artists. Since 1981, the summer market has included a youth market with exhibitors aged 7-17 who are mentored by older artists. The society also sends artists into local schools for residency programs. "As with so many communities, art here in New Mexico has been severely hit by budget cutbacks, and so we pay our artists to go out into the schools and do workshops with the children and the teachers, the results of which are a completed art piece by every student. We often have shows of the youth-artist work here at the museum as a way to get the children and their families in the museum to see other artwork beyond just what the child has done," said Pedace.

The society is partnering with other Santa Fe organizations, such as the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, to program a slate of activities that will culminate in the Spanish Market. Pedace said, "We're looking at making this more of a week-long journey in the culture with cooperative efforts between ourselves and other nonprofits in town and bringing people to town for a longer stay, to be more immersed in the culture."

Despite its traditional roots, the Spanish Market also has a forward-looking focus: this year was the debut of a new category -- Innovations within Traditions. Open to artists who had shown at the event for at least two years, this category spotlighted contemporary artwork that used traditional methods and materials. Not surprisingly, Carrillo -- who has started making santos depicted as driving pick-up trucks and vintage cars -- was one of the approximately 20 artists who showed in the new category. "I've been hoping for years that they would open the gate a little bit and allow some contemporary aspect to creep in. But I am also the one that's going to promote if you're going to open up market that way, that [you] demand that people bring both traditions to market, the old and the new because I think people need to be grounded in the old before then can move to the new."