Reading in Sunshine

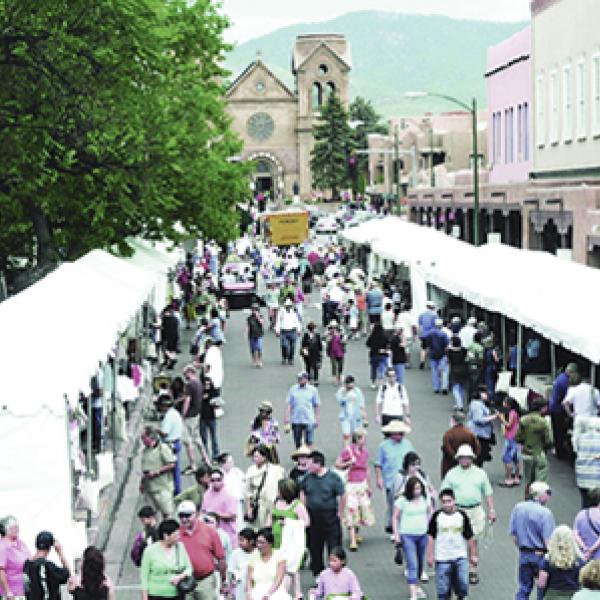

The Printers Row Lit Fest spread out before historic Dearborn Station in Chicago. All photos by Glenn Kaupert, courtesy of the Chicago Tribune

Talk to any technophile, and they'll tell you the same thing: books are for dinosaurs; newspapers are dead. Blog posts are the new literary essay, and the only sentences worth reading are those composed of 140 characters or less. If this were true, then a book festival, particularly one owned by a newspaper, is as culturally relevant as the VHS tape.

Yet the Printers Row Lit Fest, produced by the Chicago Tribune, has continued to grow, drawing 132,000 people, 200 authors, and 147 booksellers over the course of two days last summer. Next June will mark the festival's 27th year, capping off nearly three decades as one of Chicago's premier literary events. Elizabeth Taylor is the literary editor at the Tribune, and one of the festival's main organizers. While she says that "people are reading really differently" in the digital age, the allure of talking about books with people, not status updates, remains as present as ever. "In this world where everything's really atomized and people communicate online and rarely meet," Taylor said, "there's this place where people can come together in this kind of collective celebration of books, reading, ideas." The success of the festival, she thinks, is proof that "there is this hunger out there."

Of course, when the festival began in 1985, worries about Kindles, iPads, and the loss of independent booksellers were far on the horizon. The event was first created by the Near South Planning Board, a neighborhood organization designed to promote its own corner of downtown Chicago. Printers Row, a historic district located along Dearborn Street just south of the Loop, was a neighborhood of particular focus. At that time, the massive factories and warehouses once responsible for printing books had become dilapidated relics of their turn-of-the-century heyday. The railroad tracks that cut through the neighborhood were abandoned, no longer needed for shipping tomes -- or anything else for that matter.

An attendee of the 2011 Lit Fest browses the books. All photos by Glenn Kaupert, courtesy of the Chicago Tribune

Bette Cerf Hill, president of the Near South Planning Board in the 1980s, was at the forefront of revitalizing Printers Row. "My job was to get people to come to this part of town, which was considered dangerous," she said. "But it was just empty. It wasn't really dangerous. There was nothing going on there."

An artist who has served on the Illinois Arts Council, Cerf Hill turned to art as a means of attracting people to the neighborhood. In 1981, the Near South Planning Board temporarily installed The Dinner Party, a large-scale sculpture by Judy Chicago, in an unused warehouse. Later, they established Sculpture Chicago, a six-week program that brought sculptors from all over the country to the city, provided them with sculpting materials, and gave them an opportunity to sculpt pre-approved designs.

"Everybody seems to have some gene, no matter how recessive, that responds to visual art, literature, creating things, doing things with your hands," Cerf Hill said. "They may not respond to all of the various [disciplines], but one or the other of the arts seems to stop people in their tracks, capture their imagination, make them want to hang around or come back."

With this in mind, what was originally called the Printers Row Book Fair was launched. Cerf Hill wanted to "bring books out in the sunshine," which is quite literally what happened given that no vendor tents were used that first year. She hoped that the normally solitary act of reading would, for one weekend, become a catalyst for bringing the community together in its enthusiasm for the written word.

|

The festival was small that first year; booksellers with new and used wares took up less than a block. But there were authors reading from their work, music was piped in, and a special area was devoted to children's books and writers. "I think the press was surprised that people considered this a fun event," Cerf Hill said. "We were really early in the book fair thing."

Although local authors were -- and continue to be -- the primary focus, the festival quickly began to attract internationally known names. Susan Sontag came. So did Ralph Ellison. The festival began to creep into adjoining blocks, and attendance rose. Though the festival "barely broke even," a program called Authors in the Schools was started, which brought children's writers into Chicago public schools to give writing workshops. "It was quite fantastic," said Cerf Hill of the program, which is still run by the Near South Planning Board today.

By the 2000s, the not-for-profit realized that the festival had outgrown its organization. Cerf Hill had done her job: people were coming to the neighborhood. Printers Row was beginning to gentrify, a development which she attributes at least partially to the fair. Today, many of the former printing warehouses have been converted into condominiums, and the area is appreciated for its proximity to the Loop. "I think people got tuned in and turned on to the fact that you could live downtown and it was fun and safe and there was a lot to do," she said.

Meanwhile, the Tribune had been looking to develop a book fair akin to L.A.'s Festival of Books, run by its sister paper the Los Angeles Times since 1996. Hoping for the festival's continued growth, the rights to the Printers Row Book Fair were sold to the Tribune in 2002. "They could promote it like no one else could afford to [do]," Cerf Hill said.

She was right. Today, the Printers Row Lit Fest, as renamed by the newspaper, offers two days of unusually creative, inventive programming. This past summer, there was the Spelling EEB, which challenged children to spell words backwards; Pitchapalooza, which allowed aspiring authors to try pitching their work to "book doctors"; and Lit After Dark, evening programming that included everything from zombie poetry readings to performances of pieces written by prisoners.

Taylor says the diversity of programs is necessary to appeal to the wide range of readers who attend the event. "One of the reasons I love [the festival] is that it's probably one of the most diverse experiences I go to in the city," she said. "You'll see babies in strollers, older people with walkers and wheelchairs, and a wide range of people from different neighborhoods and different walks of life."

A flash mob dances to raise awareness for the Chicago Tribune's Make Your Mark literacy campaign. All photos by Glenn Kaupert, courtesy of the Chicago Tribune |

Audience diversity extends to reading levels as well, and organizers are highly cognizant of the new and struggling readers who might be at the event. According to a literacy campaign sponsored by the Tribune, 53 percent of adults in Chicago have low or limited literacy skills. Last summer, a flash mob was held at the festival to highlight this issue, and visitors were encouraged to sign a "Make Your Mark" pledge to get the city reading. Festival partners include not-for-profit organizations such as Open Books, 826CHI, and the Chicago Public Library, each of which works to improve reading and writing skills of city residents.

Although illiteracy remains the festival's most prominent cause, the event has quietly influenced Chicago in other, more subtle ways. One is by promoting the city's independent booksellers, who have struggled in the age of superstores. Another is by bringing together an annual collection of local authors, who, like visitors, are offered a unique chance to mingle with one another, share ideas, and glean new insights into their colleagues' work. Taylor believes this final element is, quite literally, helping rewrite history.

"This is a great literary town," she said, referring to a past that includes Saul Bellow, Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Lorraine Hansberry. "I think that events like the Printers Row Lit Fest keep redefining the literary history and legacy every year. By bringing writers together, they affect one another and the literature changes."

Despite the many changes and continued expansion, the Lit Fest has managed to retain its community-oriented, hometown feel. Some vendors, like Sandmeyer's Bookstore, have been there since the festival started. Cerf Hill still attends the event, nostalgic though it makes her. She says the festival's essence is the same as it ever was: people strolling the streets, "celebrating the written word out in the sunshine."