What's Going On?

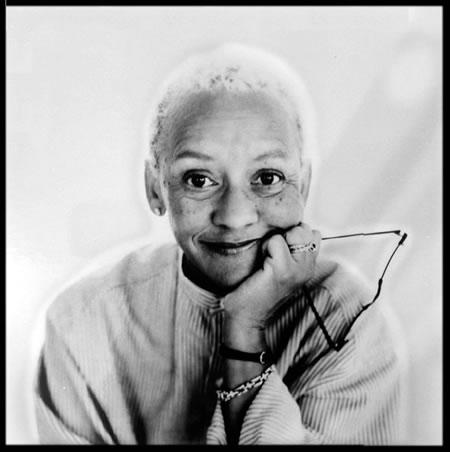

Photo courtesy of Nikki Giovanni

According to Nikki Giovanni—poet, activist, professor, Grammy nominee—Columbia University owes her a degree. As Giovanni related, "I was at Columbia University in an MFA program, and the object there was you did two years of school and you had to have a publishable book."

So Giovanni wrote and self-published her first collection, Black Feeling, Black Talk in her first year of the program. "I thought, 'Well, then if I publish this book, I'll get my MFA and, you know, go on about my business.'" Columbia, however, took issue with Giovanni's accelerated timetable. "They were like, 'Miss Giovanni, you don't understand—this is a two-year program,'" she remembered. "[And I said,] 'No, no, this is a program for me to publish a book.'" So Giovanni left the university with a book but without a master's degree.

Giovanni laughed retelling this story, a tale that underscores her drive, tenacity, and outright gumption. That willingness to go her own way has led not just to an enduring literary career, but also a slew of honorary doctorates and civic, industry, and cultural awards. In 2009, HarperCollins published Giovanni's 17th poetry collection, Bicycle: Love Poems, which was praised by Booklist as "disarming, sly, sensual, and knowing." While the poet's voice may now be tempered with the sadness of many losses, including losing her mother and sister to lung cancer—which Giovanni herself has battled—the poet who in 1968 wrote "I wanted to write/a poem/that rhymes/but revolution doesn't lend/ itself to be-bopping" still has plenty to say.

According to Giovanni, she absorbed her vocation from her native ground. "I'm a Tennessean by birth, and I'm an eastern Tennessean. If I had been born in Memphis I probably would have been a blues singer. But in Knoxville, Tennessee, we mostly are storytellers." As a child she heard stories on front porches, at church, and, most important, at the salon where she waited on Saturdays for her hair to be washed and pressed in between adult appointments. "I would just sit there, and I'd sit quietly, and pretty soon they'd forget about me, and I would hear a lot of really interesting things," Giovanni recalled. "So I got in the habit of [thinking], 'Oh I wonder what the story really is.' I would not have formed that question at that time, but ultimately that's what I came to as I became aware of literature and stuff. You start to say to yourself, 'I wonder whose story this is. I wonder what's really going on here.'

"Basically I'm always walking around with a question in my head, whether or not I actually sit down [to write]," she explained. "Sometimes an image [starts a poem] but it's usually a question. I'm a 'What if?' person. So you start to see things, and you wonder about them."

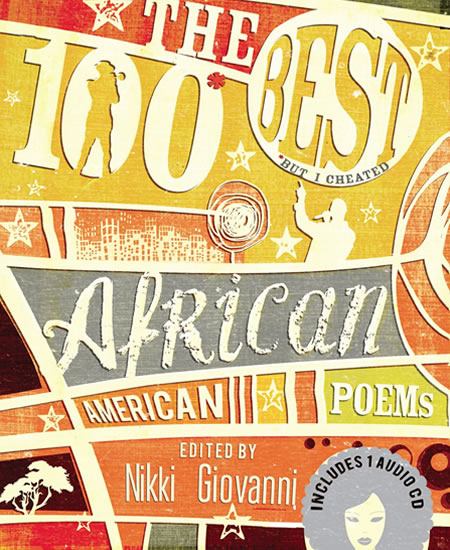

The 100 Best African American Poems, edited by Nikki Giovanni. Image courtesy of Sourcebooks |

While her poetry may have traditional roots, Giovanni's career has been decidedly forward-thinking. She was making recordings such as 1971's Truth is On Its Way long before spoken word became a phenomenon. Self-publishing was also not the norm in 1968 when Giovanni published the collection she'd polished at Columbia. "I found a printer in Pennsylvania, and he [said], 'Okay, I can give you 500 books for $500.' So I borrowed some money from my grandmother and some other friends and bought 500 books…. Well, you have to take them around, which I did, to the coffee houses and stuff," remembered the poet.

She took to the airwaves to publicize her second book, Black Judgement, which was supported by an NEA Discovery grant. (A short-lived program, these awards were given to artists based on financial need as well as artistic merit.) Giovanni recalled thinking, "I am gonna make sure the people who might want this book know it exists…. AM radio was ruling the roost, and so I just went down to the radio shows and was like, 'Hi, would you like to have some poetry read?' I don't want to be falsely humble but I think that this career has been helpful to the poetry movement because I would do things like that, and when people would say, 'Well, Nikki did it,' people would start doing it, and I think it raised the poetry profile in the nontraditional community."

Giovanni's work was heavily influenced by Langston Hughes, especially his remark, "We will write about our own black selves." She explained, "That was the right thing to do. What else are you going to write about? Can you really see me doing a British novel about fox hunting in the highlands, or for that matter, a poem? That is stupid. You write about what you know…. [W]e argue from the particular to the universal, not the other way around. That only makes sense."

Still, while Giovanni's work focused on African-American subjects, she was uneasy with the question of an African-American aesthetic, an idea with which she still grapples. "I didn't understand, because nobody ever talked about the white aesthetic or the brown aesthetic…. [T]hese things never came up with the Asian-American aesthetic. It still confuses me. I wrote and I write and I try to write what I understand and what I love, like any other writer, and I think of that as an incredibly inclusive process."

This is a philosophy that Giovanni endeavors to pass on to her students at conferences and workshops and at Virginia Tech University in Blacksburg, where she has been on faculty—and a fervent Hokies fan—since 1987. For Giovanni, teaching is a two-way street benefiting the teacher as much as the student. "Everybody that I do know—and that'd be from Toni Morrison to Maya Angelou—all teach because it keeps you young…. It puts you in essentially what's an uncomfortable situation, which requires that instead of [contemplation] you have to project. This is incredibly good for you if you're a writer because writing is a solitary profession, and if you're not careful you'll end up in that Ernest Hemingway mode."

While age has grayed her hair and she has been known to refer to herself as a "little old lady," Giovanni remains as outspoken as ever, even sporting a controversial "Thug Life" tattoo inked to honor the late rapper Tupac Shakur. And she's not afraid to make statements that might make others uncomfortable, such as linking the deaths of Shakur and John F. Kennedy, Jr. "When you compare—I shouldn't say 'compare' but 'pair'—the deaths of John Kennedy, Jr. and Tupac, America lost two of its really wonderful sons that were going to be able to—or we had hoped—begin to take the nation in another direction in terms of how we feel, how we look at ourselves. And so I think those are two great losses."

A frequent guest speaker—even at Columbia University—Giovanni still possesses that rare gift of saying the exact thing that needs saying even under the most difficult circumstances. The same unfussy plainspeak that powered early poems such as the love poem, "Kidnap Poem," and the brief but powerful elegy, "The Funeral of Martin Luther King, Jr." permeates work addressing the questions the poet ponders today. How do you talk about being in love as a senior citizen? How do you put words around the legacy of the civil rights movement? Hers was the voice that articulated the collective grief and hope for healing of the Virginia Tech University community after the 2007 campus shooting. Her poem "We are Virginia Tech," reads, "We are strong enough to stand tall tearlessly, we are brave enough to bend to cry, and we are sad enough to know that we must laugh again."

And, of course, sometimes it still behooves Giovanni to play by her own rules when it comes to publishing, especially if it's in the service of promoting others. Take for instance 2010's The 100 Best African American Poems published by Sourcebooks. A quick glance at the table of contents reveals that the anthology actually contains 115 poems. Giovanni explained, "I definitely cheated because I wanted one-fourth of the book to be young people. And I said to my publisher, 'If a church doesn't have Sunday school, pretty soon there won't be church.' And so devoting a significant portion of that book to young writers, I think, was important."

Asked to identify the most significant moments of her career, Giovanni quipped, "I don't do retrospective right now. I'm just 68!" There is, however, a thread that clearly connects Giovanni's past and present career: she sees her work—as writer, as teacher, as advocate— as a form of citizenship. "[Writers] are like anybody else. We're like the teacher, the preacher. We're like the restaurant owner," she affirmed. "We're citizens and sometimes people let writers think that they should be more…. 'If you're a good writer, why don't you change the world?' Well, writers don't change the world. The world changes and we write about it.

"We're like a really good mom-and-pop restaurant," she added. "Our job is for that little restaurant to do the best food we can do so that when people do come, they are fulfilled."