The Influence of Africa on U.S. Culture

When Ponce de Léon first stepped foot on Florida soil in 1513, he opened the flood gates to European settlement, and its contingent influence on language, religion, and culture. But his arrival marked the start of another influential cross current as well. Juan Garrido, a free African-Spanish conquistador, was a member of de Léon’s expedition, and is thought to represent the first African presence in Florida. No one, of course, could predict that he would be the first of millions to cross the Atlantic, mostly in chains, bringing their memories and customs along with them.

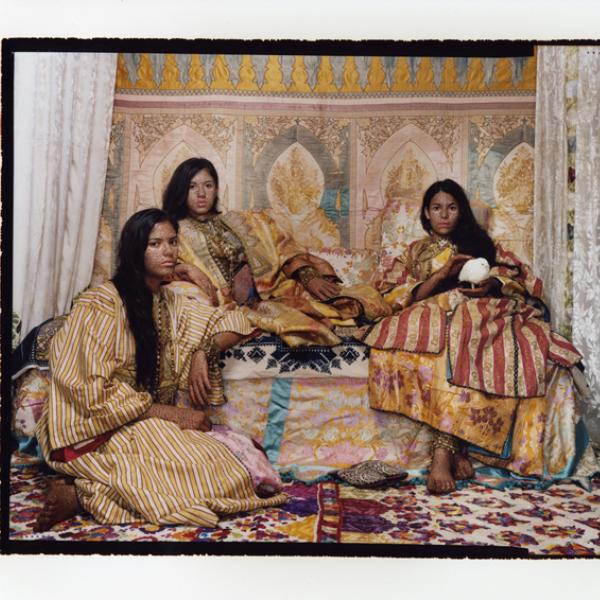

To commemorate the 500th anniversary of Garrido’s landing, the Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida organized Kongo across the Waters, which coincided with the statewide Viva Florida 500 celebration honoring de Léon’s journey. The show, which closed in March and will open at the Carter Presidential Library and Museum in May, focuses on the Kongo Kingdom—which included parts of what is now Angola, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—and the continued influence of modern Kongo culture. The exhibit borrows heavily from the collection of Belgium’s Royal Museum of Central Africa—a process facilitated by the NEA-administered Arts and Artifacts Indemnity Program—and examines how interaction with Europeans affected life in Kongo across the centuries, and concurrently, how the Kongo diaspora has imprinted African-American culture and artists.

“[People] think Africa is one big amorphous area,” said Susan Cooksey, a curator of African art at the Harn. But by tracing certain practices and art forms back to Kongo culture specifically, Cooksey hopes visitors will better appreciate the distinctive ways Kongo culture integrated itself into American life. “We have refined our view of what our heritage as Americans is,” said Cooksey. “We can see through this exhibition that some of the roots of people here go back to specific places, to specific cultures. And they’re still living. They’re still very important to us; they still impact us.”

Sweetgrass Baskets

One of the more obvious examples of Kongo influence can be seen through two baskets on display, which bear parallel techniques, proportions, and shapes. Though they are strikingly similar, their provenances are separated by hundreds of years and thousands of miles: the first is from early 20th-century Kongo, while the other is a 2012 sweetgrass basket by Barbara Manigault, who hails from South Carolina. The latter represents an art form prevalent among the Sea Islands bordering South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, particularly among communities like the Gullah whose unique culture continues to bear strong traces of African roots.

These roots, of course, stem back to slavery, when slaves from Kongo and surrounding areas—a region known as the “rice coast”—were frequently sold to plantation owners living on the Sea Islands, who relied on slaves’ knowledge to fuel their own burgeoning rice industry. As new slaves were brought over from the same parts of Africa, traditions such as basket weaving were reinforced, and eventually passed down through the generations. Although these baskets were initially used for rice winnowing or storing crops, today they have been elevated to an art form, and several NEA National Heritage Fellows, including Mary Jackson and Mary Jane Manigault, have been recognized for the exquisite craftsmanship of their sweetgrass baskets.

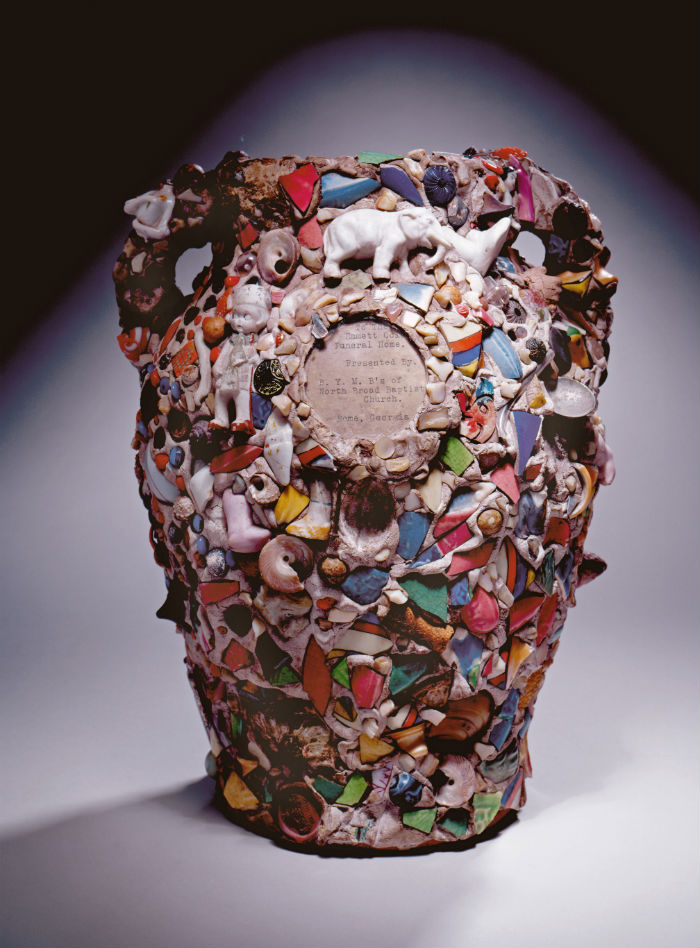

Memory Jar

Another piece on display is a 20th-century “memory jar.” Memory jars were common among southern African-American communities, and were thought to have been used as grave markers, or perhaps simply as a way to honor the dead. Cooksey believes these jars, which were typically decorated with possessions of the deceased, bits of porcelain, and seashells, can trace their origins to the Kongo. Kongolese burial rites also entailed covering graves with belongings from the dead, which frequently included crockery. The seashells found on memory jars also suggest Kongolese origins, as Kongolese believed the dead inhabited a spiritual realm that was connected to our world by water.

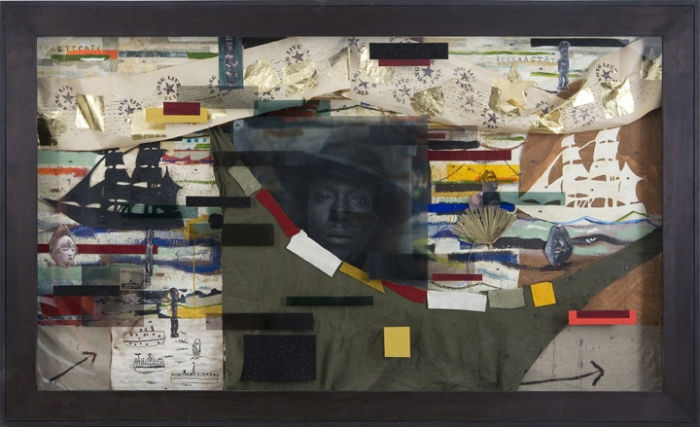

Radcliffe Bailey’s Returnal

The final part of the exhibit explores Kongolese influence on five contemporary artists, including the American painter, sculptor, and mixed media artist Radcliffe Bailey. In many of his works, Bailey “talks about collective history of African Americans and personal history all at the same time,” said Cooksey. “He thinks of [his art] as finding a cure for this loss of memory—this amnesia—that so many African Americans, including himself, have had about their past.” In his own quest to remember, Bailey had his DNA tested, and Returnal is inscribed with sequences of his DNA that connect him with West Africa. The artwork also includes a number of images of slave ships, as will as minkisi, or small figures thought to be inhabited by spirits. Minkisi were a common feature in Kongolese religious practices, and a number of them are on display in Kongo across the Waters.

Drums & Music

Beyond visual art, the Kongo region has also had a major impact on American music. In a film featured at the exhibit, an ethnomusicologist and a percussionist in Congo Square in New Orleans discuss musical practices thought to originate in West Africa, including call and response forms, ring shouts, and of course, the earliest forms of jazz. One of the items on display is a long, tapered drum from early 20th-century Lower Congo region. The drum, which meant to be straddled, is reminiscent of what we now call a conga drum, whose name alone suggests its ties to Kongo music.