Literature's Invisible Art

Translation is an invisible art: the better it is, the less you notice it. At the art form’s pinnacle, a text reads so naturally that one might not even realize it is a translation at all. Few people, for example, stop to think that well-known phrases such as “all for one and one for all,” “ye who enter, abandon all hope,” and “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way” were originally written in a language other than English (they appear in The Three Musketeers, Inferno, and Anna Karenina, respectively). These lines, and the works they are from, have become as much a part of American culture as the culture of their mother tongue.

Yet even with translation’s clear importance to cultural life, American translations are exceedingly few. According to the University of Rochester’s Three Percent website, only three percent or so of all books published in the U.S. each year are works of translation. When calculating only literary fiction and poetry, this figure dwindles to 0.7 percent, or 517 titles in 2013. Even this paltry amount requires hours of painstaking, time-intensive, and frequently thankless work, overlaid by the anxiety of choosing the correct word, the right tone, and the proper syntax.

Photo by Rachel Carlson

Nancy Naomi Carlson is no stranger to these labors of language. She has translated works of poetry by René Char and Suzanne Dracius from French into English, and also serves as the translation editor for the Blue Lyra Review. Her latest project, supported by a 2014 NEA Translation Fellowship, is the translation of Abdourahman Waberi’s first collection of poetry. Like his novels, which include Passage of Tears and In the United States of Africa, the poems in The Nomads, My Brothers, Go Out to Drink from the Big Dipper draw on Waberi’s experience as a youth in Djibouti, and later, as something of a self-imposed exile based in France. The collection, published in French in 2000 and reissued in 2013, will be published in English by Seagull Books next spring.

Like Carlson’s past projects, the translation process for The Nomads follows an arduous path. For all her translations, she works with two French-English dictionaries, an English-English dictionary, two online French-English dictionaries, two online French-French dictionaries, and a thesaurus. Her initial drafts include all possible word choices, which she narrows down according to the original verse’s style and meaning. Dracius, for example, writes lengthy poems with flowery language and frequent Greco-Roman references; Carlson chose similarly sumptuous English parallels. On the other hand, “Abdou’s work is miniature—just like the Republic of Djibouti,” Carlson said. “He says a lot with a few lines and very simple words.” In accordance, her Waberi translations are written in succinct, unadorned English.

Many poetry translators stop here: conveying the tone and content of a poem is enough. But for Carlson, who studied music and is a poet herself, sound is almost as significant as content. “Without even trying, [French] is so rich in sound,” she said, noting that this quality is amplified by a poet’s pen. “How can you ignore that?”

For each poem, Carlson creates what she calls “sound maps,” color-coded charts that track alliteration, assonance, and syllabic stresses in the original verse. She replicates these rhythms and sound patterns as best she can, attempting to preserve the poem’s musicality. Of course, certain linguistic limitations are unavoidable, which Carlson negotiates with a bit of creative license. “You can’t get the exact sound for a line in French,” she said. “Many of the sounds—the nasals—don’t exist in English, so I couldn’t possibly do that. But if I can maybe get another sound pattern going, and maybe it happens to be on this line instead of that line, if it’s infused in there, then I’ve done my job.”

Eventually, these words, sounds, and meanings are stitched seamlessly together, ideally creating a text that is at once accurate and beautiful. And yet, “There’s always going to be a flaw,” said Carlson. No matter how long you might work at it, “It’s always going to be imperfect.” She invoked a quote by Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko: “Translation is like a woman. If it is beautiful, it is not faithful. If it is faithful, it is most certainly not beautiful.”

Regardless, perfection—or at least its close relative— is always the goal. For her Waberi translations, Carlson had a unique advantage in this pursuit: the author himself. When she first contacted Waberi about translating his work, Carlson was unaware that he was a visiting professor at the George Washington University, just a few subway stops south of where she herself teaches at the University of the District of Columbia. As a result of the serendipitous proximity, the two developed a close collaboration as the work progressed. Carlson consulted Waberi on word choice and narrative intention—especially helpful given his occasional use of Somali—and Waberi offered suggestions while trying not to overstep his role.

“It’s a question of humility,” he said, when asked how it felt to watch his work translated into a language he speaks fluently. When one of his novels was translated into Serbian, he said it was easy to let go; since he doesn’t speak the language, he remains blissfully ignorant of whether the translation was up to snuff. His English translations, he thinks, are no different. “Why should I intervene? Because I speak some English?” he asked. “[The translator] is doing his or her job, and I’ve done mine.”

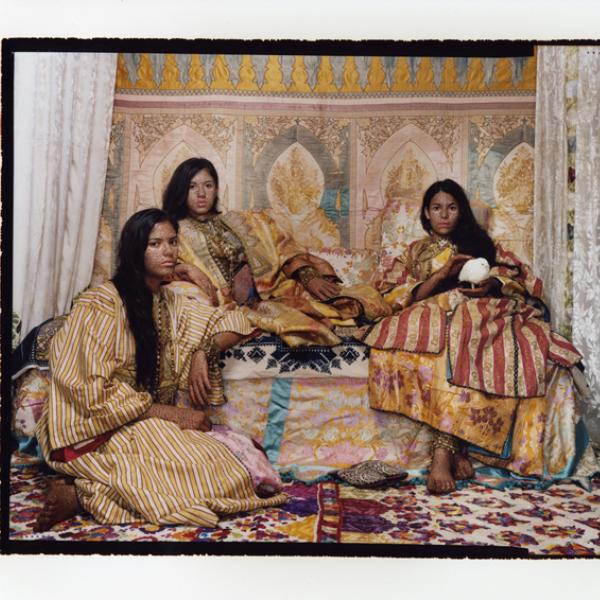

Given the pair’s intimate working relationship, Carlson also had a comprehensive primer on Waberi’s native culture, which she believes is essential for literary translations. “As a counselor, my job is to empathize and walk in someone else’s shoes,” said Carlson, who has a PhD in counselor education and has worked in school counseling since 1978. “If you can’t [do that], I think it’s impossible to translate. I don’t feel that people can look at the French, especially in poetry with all the nuances and the lyricism, without understanding where that’s coming from, without understanding the sparseness of Djibouti. The sparseness of Abdou’s poetry represents a sparseness of the desert, the nomadic life, the few belongings, not burdening yourself down with things and traveling light in the world.”

Beyond her conversations with Waberi, Carlson made it a point to learn about Djibouti’s history, political system, and culture, just as she did with Martinique, where Dracius is from. “I have two PhDs because I love to learn,” she said. “I feel like I’m in another course, as I translate, of World 101.”

It’s a feeling she hopes readers will share as they read Waberi’s work. “From my point of view, it’s fascinating for an American audience to get a bird’s eye view into Djibouti,” she said. “Many of them have never heard of Djibouti, let alone know where it is, what the political scene is right now, what the landscape is like. I’m hoping others will go, ‘Oh my goodness, how different, how exotic, how sad, how exciting.’”

And perhaps, even, “how familiar.” Although international readers might not have direct knowledge of Djibouti, Waberi said his work is more about a shared emotional state than a particular place; the country name, he said, could be swapped with almost any other. “I’m writing from a human condition of displacement,” he said. “That is the great experience of this century, how people moved and have this experience of displacement worldwide.”

“You go to the deepest core of the text…and you say, ‘Come on, we’re speaking the same language,’” he continued. “You discover you’re not very different.”