Trying to Find Their Way

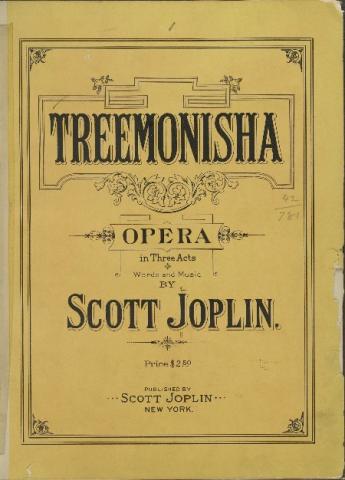

In 1911, noted Black composer Scott Joplin published a piano-vocal score of his opera Treemonisha with his own money—using up almost all of his savings—after being turned down by other publishers. There also were no takers for staging the production in New York, and the only performance of the opera in his lifetime was a concert recital in 1915 in Harlem, also paid for by Joplin. The music was much different from the ragtime compositions he was known for, and the story wildly progressive for its time: a young Black woman named Treemonisha is chosen to lead her community, using her education to defeat the conjurers who used superstition to prey on the people. Equally progressive, the opera was written to feature an all-Black cast. The rejection of the opera proved too much for Joplin, who suffered a breakdown and ended up in a pauper’s grave in 1917, his orchestrations to the opera discarded.

But Joplin’s opera wasn’t forgotten and was revived in the late 20th century, getting its first full staging in 1972 by Morehouse College, one of the nation’s historically black colleges and universities, with the Atlanta Symphony, followed by a professional premiere in 1975 by the Houston Grand Opera. In 1976, Joplin was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize for his contributions to American music, 59 years after his death.

In this centennial year of women’s suffrage, Treemonisha makes another revival with support from the National Endowment for the Arts and other international collaborators. Presented in a new, contemporary light, the production is being produced by the Canadian groups Volcano Theatre and Moveable Beast Collective, and was commissioned by Stanford Live, Washington Performing Arts, Minnesota Opera, the National Arts Centre and Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in Canada, and Southbank Centre in England.

“The fact that [Joplin] chose to write an opera only for Black singers was an artistic decision, because he knew probably that most white presenters—which were [the only presenters] at the time—would not be interested in presenting that,” noted playwright Leah- Simone Bowen, who adapted the story and was co-librettist with Cheryl Davis. “He knew that he probably would have to produce it himself, and he did it anyway. So it only makes sense that the [Volcano] team would be primarily a Black creative team. It really follows in the footsteps of what Joplin wanted to create.”

Bowen kept the core of the story intact: that Treemonisha is educated and uses her intelligence to lead the community. But what Joplin presented as ignorance—people rooted in superstition and conjuring—Bowen presents as being part of the African tradition that had been lost during slavery. “Treemonisha, as a leader, ends up holding onto both sides of herself and her people, which is the African and the American.” To enhance that connection between the African and the American, the musical arrangers—Jessie Montgomery and Jannina Norpoth, both based in New York City—used both Western and African instruments in the arrangements. While Act One follows Joplin’s score, Acts Two and Three depart from it with the addition of African influences. The all-Black, majority women chamber orchestra included a string quartet, jazz instruments such as trumpet and clarinet, and the kora, a 21-stringed instrument from West Africa. “The kora is such a versatile instrument: it can sound like itself and it can also sound like a harpsichord or a harp, so it can very seamlessly go back and forth through many styles of music,” said Norpoth. “From a historical standpoint, the kora is a storytelling instrument. The kora players in Africa come from generations of kora players, and they’re the historians.” The kora’s use enhanced the idea Bowen puts forth in the story about the importance of traditions that were lost when Africans were brought to America as enslaved people.

The arrangers filled out the story and smoothed out certain plot points by using several other songs by Joplin, including his ragtime composition “A Picture of Her Face.” “It’s very beautiful and reflectively joyful, but also with a twinge of sadness,” said Norpoth of the song. “Ragtime has a certain style, and even the sad music still sounds happy. I think it’s reflective of being a Black person during that time and having to be so repressed about the ways society was oppressing you, and having to show that in a very understated way.”

While some might grumble about revising Joplin’s work, Bowen thinks otherwise. “Shakespeare has lived on and is lauded, and people redo his work and change his work and do adaptations, because he was a genius,” she said. “That work is used as a jumping-off point. I think Joplin is a genius and deserves that, and I wish more Black artists, globally, of this time period and before, would get this kind of tribute. I do feel like it is a tribute to him, and that we’re honoring him.”

Although the opera was scheduled to premiere at Stanford University in late April, the global pandemic interfered. “We were about three weeks from having the whole company land on our doorstep, and that’s when everything essentially got called,” said Lorway. “There have been a number of company workshops over the last few years, and different groups—both locally and internationally—have gotten together and have done a lot of planning. This was really going to be the home stretch and literally we just missed it by weeks.” With the complexity of schedules involved, Lorway suggested that most likely they would postpone the production until 2022.

Norpoth is looking forward to that day. “I’m confident that it will happen in the future and it will be just as relevant and just as important and just as needed, and maybe more needed after all of this time where we haven’t been able to experience live music.”

While it missed premiering during the centennial of the 19th Amendment, it still connects with women’s journey for equality. When Bowen was writing the story adaption, she was thinking about who would be the Treemonisha of Joplin’s day. “A lot of my inspiration and research when I was looking at Joplin was also about [women’s rights and civil rights activist] Ida B. Wells,” she said. “There are wisps of Ida B. Wells all through Treemonisha. I think it’s really important when we talk about these movements to remind ourselves that Black women have always had to fight not only for the equality of women’s rights, but also as African Americans.”

Joplin’s story about a strong Black woman selected by men and women to lead their community—written a decade before women could even vote nationally in the country—is a story that still resonates today. “The beauty of Treemonisha is that Joplin chose to write this [opera] about a story that was really happening in his community,” Bowen said. “It is, of course, about America and the time of Reconstruction. But it’s also about a group of people trying to find their way.”