Nourishing a Community

Buffalo had, for far too long, a narrative of being just another Rust Belt city,” said Barbara Cole, artistic director of Just Buffalo Literary Center (JBLC). “Despite that overarching narrative of Buffalo being a city of decline, the arts and cultural community has always been vibrant here, and Buffalo has always been a destination for artists of all kinds. So the arts have taken a leadership role in trying to help change that narrative.”

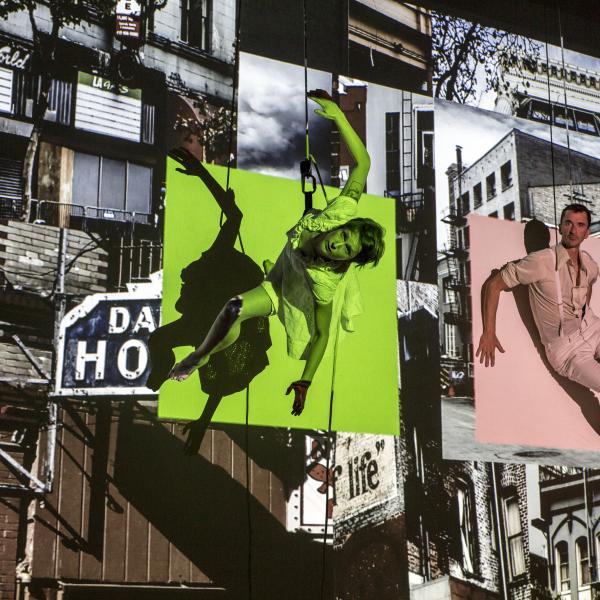

JBLC has been one of the arts organizations on the frontlines of challenging that narrative by providing multiple points of entry into the world of literature and helping ensure Buffalo maintains healthy literary roots. Its programming ranges from its acclaimed reading series, BABEL, that brings the world’s most significant authors to Western New York; to the Writing Center that houses summer camps, literary programming, and free after-school writing workshops for teens; to LIT CITY, a public art initiative highlighting Buffalo’s renowned literary legacy. The National Endowment for the Arts has been supporting many of these programs since 1989.

But with new narratives come new challenges. While Buffalo has experienced a “resurgence” in recent years, JBLC wants to make sure the city’s renaissance story isn’t leaving anyone out. “We’re really trying to remember how many people have been here for a long time, or how many people might be invisible in that story of resurgence,” Cole said, adding that the center is also concerned with “making sure that underserved populations are getting the services they need and the attention they deserve.” In recent years, JBLC has turned its attention to public art. “We’re very aware that some people—for a variety of reasons—don’t necessarily want to come hear an author read,” said Cole. “So we’ve been thinking increasingly about public art and how we can bring literature to people rather than asking them to come to us.”

|

This led to READ | SEED | WRITE, a project of JBLC in collaboration with Grassroots Gardens WNY, an organization dedicated to community gardening. The goal was to make the literary arts more visible, inspiring both gardeners and members of the community through the written word, while also raising awareness about the importance of sustainable gardening and the need for urban access to healthy food.

As JBLC Executive Director Laurie Dean Torrell noted, nourishing a community or an individual includes “access to healthy, community-based, sustainable food, and also access to poetry and literature.” The project, which was supported by an NEA Creativity Connects grant, involved holding writing workshops in community gardens, using the garden as a metaphor for participants’ writing, and erecting permanent sculptures in each garden with words inscribed onto the leaves of a rising stalk.

READ | SEED | WRITE was dreamed up during a brainstorming session. For years, many of JBLC’s staff had been interested in food politics and were passionate about health and wellness within the city. They had been thinking about how those interests intersected with JBLC’s literary mission and were conceptualizing possible projects when a volunteer, George DeTitta, walked into the room. A retired scientist, DeTitta had been volunteering at both JBLC and Grassroots Gardens WNY. He thought the organizations’ respective missions aligned in many ways, and suggested the two organizations collaborate.

“We still didn’t fully know what the project would be until we started talking to Grassroots Gardens,” said Cole. Grassroots Gardens’ mission is, according to its website, to “enable community-led efforts to revitalize the city and enhance quality of life through the creation and maintenance of community gardens that bear both beauty and healthy foods and help strengthen neighborhood spirit.”

|

Together, JBLC and Grassroots Gardens identified four community gardens for programming: Black Rock Heritage Garden, Victoria Avenue Community Garden, Seneca Babcock Community Garden, and International School #45 Community Garden. “These neighborhoods are primarily food deserts and oftentimes impoverished communities that don’t have access to healthy foods,” said Cole. “So we were simultaneously trying to raise awareness to the larger community about why these community gardens are so important, why it’s necessary to have access to healthy food, and also to use literature as a way to bring those communities together, to inspire people right where they are.”

Because each garden is its own microcosm that serves communities with different demographics, programming catered to the needs of each garden community. The Black Rock Heritage Garden, for example, is the oldest community garden in the city of Buffalo, and the site of many historic battles from the War of 1812. Melissa Fratello, Grassroots Gardens’ former executive director who worked on READ | SEED | WRITE, called this garden the organization’s only “binational peace garden, and one that celebrates history through the plants grown there, as well as [through] sculptures and neighborhood activities.” Seneca Babcock Community Garden is primarily a community center with various programming for youth and seniors. International School #45 is exactly what it sounds like: an elementary school that serves diverse immigrant and refugee populations on the city’s West Side.

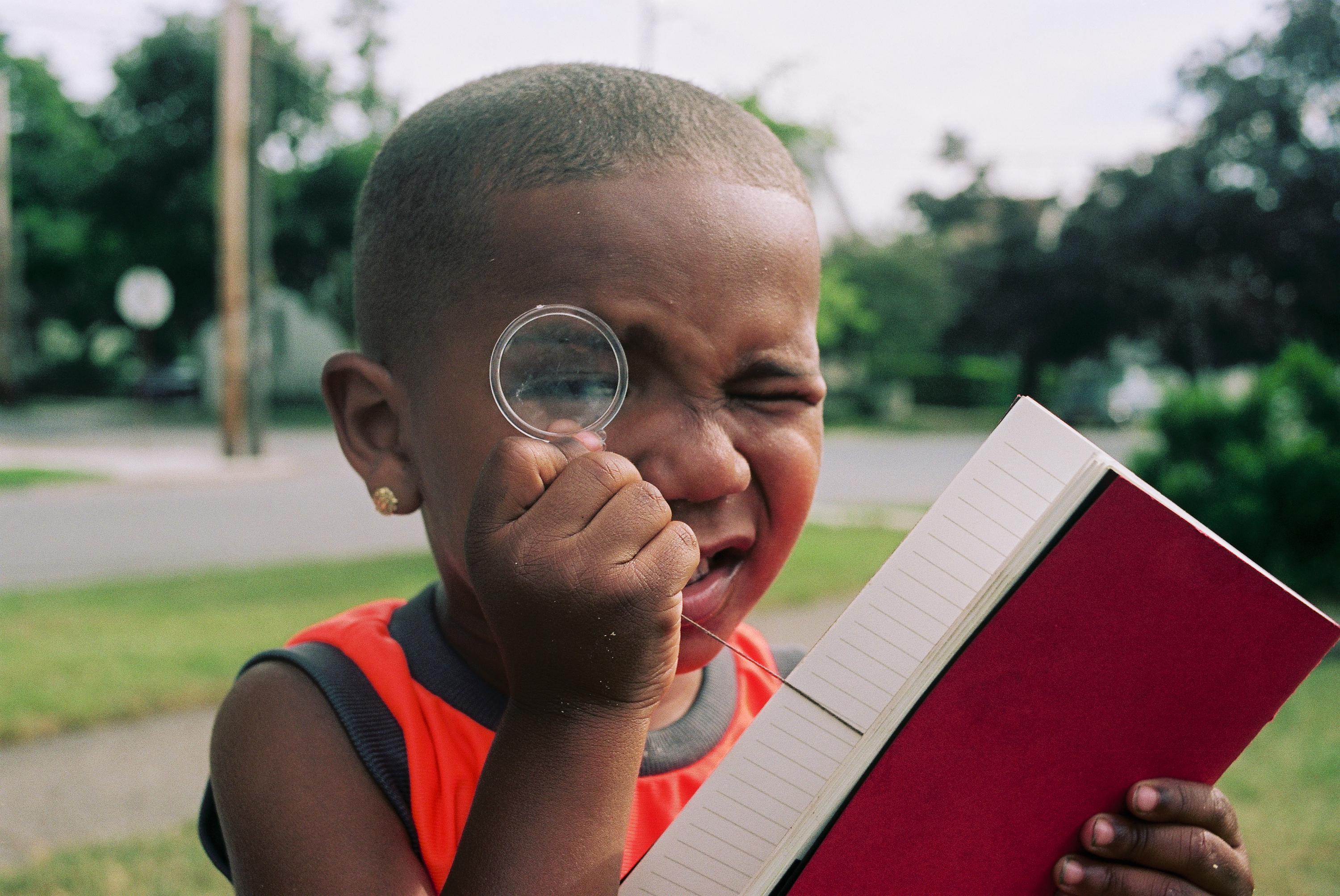

Teaching artist Christina Vega-Westhoff worked at International School #45 as part of a summer school program for recent immigrants and refugees. “For most of the students, it was their first time in the school’s garden. They were all English language learners, and some students were just beginning to learn the alphabet,” Vega-Westhoff said. “Plants became a touchstone for storytelling and multilingual word sharing. We read words and poems aloud together, and used list poem strategies and word boxes.”

Participants at all of the gardens made garden journals with book artist Joel Brenden. Each journal was adorned with a magnifying glass “to look more closely,” Vega-Westhoff explained. Groups used their senses to become familiar with the garden, which helped prompt words to describe what they found. “We heard soil buzzing, mint dancing, broccoli singing a sad song, peas playing the drums,” she elaborated.

|

Two students at International School #45, a kindergartener and a third-grader, had recently passed away when the READ | SEED | WRITE program was in the planning stages. The community expressed a desire to pay tribute to those students and one of the teaching artists suggested making seed paper. For the project, each student made their own paper embedded with marigold seeds, wrote a poem on it to their lost classmate or someone else in their life they wanted to honor, and planted it. “When the other gardens heard about that project, they said, ‘Oh, we want to do that too, we’ve lost members of the community,’ and that quickly became something we decided to do in all four gardens,” Cole said.

Another project that also spread to all four gardens was a community cookbook. Gerldine Wilson and other members of the Victoria Avenue Community Garden wanted to make a cookbook with recipes using ingredients from the garden as a way to help educate other gardeners and members of the community about healthy cooking. Other gardens were excited by this idea and wanted to join in. Ultimately, the cookbook included recipes from all four community gardens, as well as writing and artwork that came out of READ | SEED | WRITE workshops. This way, Cole said, “[the cookbook] would really tell the story of the whole project and the whole city as opposed to a fractured, divided city.”

The program’s culminating event was a Harvest Celebration, which brought together members from more than 100 community gardens in Western New York and included cookbook contributors reading their work.

While there aren’t definite plans to continue READ | SEED | WRITE programming, the cookbook and garden sculptures will serve as lasting mementos and sources of inspiration. Cole is also hopeful that literary organizations from other cities will be able to replicate the program. After serving on a panel called “Everywhere, A Poem: Poetry as Public Art” at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs Conference this year, Cole talked about READ | SEED | WRITE to a packed audience. She thought many organizations were intrigued by the project, and felt that they could duplicate it in their own communities. In that way, the project might grow to bear fruit all across the country.

Katy Day is an assistant grants management specialist in the Literature office at the National Endowment for the Arts.