Transcript of conversation with Benny Golson

Music

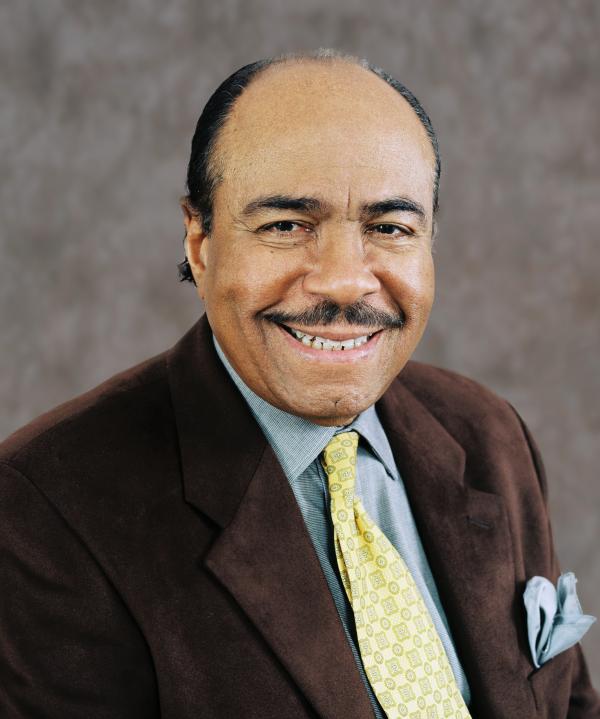

That is 1996 Jazz master Benny Golson playing his own tune, "Stablemates."

Welcome to Art Works, the program that goes behind the scenes with some of the nation’s great artists to explore how art works. I’m your host Josephine Reed.

Benny Golson not only plays a terrific tenor sax, he’s also probably most important living composer in jazz today.

Born and raised in Philadelphia, benny began studying the piano when he was 9, but within a few years, he moved to the saxophone. While he was in high school, Golson played with several other young and hungry musicians, , including Jimmy and Percy Heath Philly Joe Jones, and his great friend, John Coltrane. When Golson went to Howard University, there was no jazz program; indeed, he wasn't even allowed to play jazz there. Times have changed. Howard now has its own jazz ensemble and gives a yearly Benny Golson Award.

After earning hisdegree from Howard, Benny Golson joined Bull Moose Jackson's band. He began arranging and composing almost immediately with the early encouragement of Jackson’s pianist Tadd Dameron. Benny also played Lionel Hampton and Johnny Hodges and toured with the Dizzy Gillespie big band from 1956-58, he then joined Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers where his solo on Bobby Timmons' song "Moanin'" became a classic. With the Messengers, Golson's writing skills blossomed as he contributed pieces for the band that have entered the jazz canon, including "Along Came Betty," "Blues March," "I Remember Clifford and "Killer Joe." After leaving the Messengers, he and Art Farmer formed the hard bop quintet known as the Jazztet.

So It came as a surprise when Golson moved to Los Angeles and left jazz to concentrate on studio and orchestral work. During this time he composed music for films and television shows like Ironside, Room 222, M*A*S*H, and Mission: Impossible. After a long hiatus, Golson returned to jazz to great acclaim, recording and composing as well as performing internationally. Benny Golson has won many awards in his long and distinguished career, including recognition as a NEA Jazz Master which he received in 1995.

Benny Golson participated in the 2012 NEA Jazz Master’s Concert...when he and Frank Wess stopped the show with their performance of the tune, "Magic." I caught up with him the following day. We spoke in the studios in Jazz at Lincoln Center. Here’s our conversation.

Jo Reed: Now when did you find the sax or how did the sax find you?

Benny Golson: I think the sacs found me, because when I started out, I started out as a nine-year-old piano student. And I fancied that I wanted to be a concert pianist. That got a few chuckles in the ghetto, when everybody was listening to the blues <laughs> and I'm talking about Chopin and Bach. I was deadly serious about it. I mean I practiced all the time. But then I went to hear-- when I was 14, I went to hear Lionel Hampton at the Earl Theater downtown, because all the kids were coming back to high school and saying "Oh man, you should hear Lionel Hampton. You should hear him playing "Flying Home" and blah, blah, blah. So one day I didn’t go to school. I went to the theater and got the surprise of my life. The band started playing while the curtain was closed and the spotlight was on the curtain of course. And an announcement was made and then the curtain slowly opened. And as that curtain opened, it was like my life, a certain portion of my life was opening, because I now began to see the saxophones in the front and I could see the trumpets behind them and little more the trombones and I could see the bass player and the piano player, the guitar player. And the lights were shining on these golden instruments and it was sparkling and it was like magic.

Flying Home up and hot

Benny Golson: And they were playing the music and then this saxophone player stood up. And he stepped out from the saxophone section and he came to the edge of the stage. I said, "Well what's he going to do?" And the microphone magically came up out of the floor and he began to play. And that's when my life changed. Saxophone, I was enamored with it. So when I went home-- we were poor, you know. We were on welfare then I think. I knew we couldn’t afford-- my mother couldn’t afford to get me a saxophone. I mean the piano lessons were very expensive, you know, 75 cents a lesson <Laughs>. And the piano--

Jo Reed: But that's a lot of money then.

Benny Golson: Then yeah. She had a job as a waitress $6 a week plus tips. And the piano teacher used to come to the house, like a doctor making house calls, for an hour. And I knew that was out of the question. So I began listening to the radio, waiting for a song that would include a saxophone solo. And my mother saw me doing this and asked me what I was doing. And I told her, you know, I heard the saxophone and I'm waiting to hear some of the saxophone solos. And when I told her, that I was really thinking about becoming a saxophone player, she had a fit. "Oh." She said, "Jazz musicians, they take dope <Laughs>." I said "Ma, I'm not interested in dope. I'm interested in the saxophone." But eventually she came around to my way of thinking. And I was thinking if I could get a horn, I could get a secondhand one. One of those old silver-looking saxophone from the pawn shop. Never thinking I could get a brand new saxophone. She wasn’t making that kind of money. And I didn’t have a father. You know, the father walked off into the sunset earlier. So it was just my mother and me. And I remember that day when she left for work, all she had was a little package with her lunch in it. But when she was coming home and she got off the street car, I saw she had something in her hand. But she was walking toward me on the other side of the street and I couldn’t see the shape. But when she turned and crossed the street, I saw that it was elongated and my heart almost jumped out of my body. I said "This can't be a saxophone. It just can't be." And when she got close enough for me to hear her voice, she leaned forward slightly and said, "I have something for you baby." I almost died. She came in the house, put the saxophone down on the counter and opened it. It was a brand new Martin's tenor saxophone. And I immediately became depressed. I thought you just picked this thing up and played it. I thought it was all in one piece. The body was in one piece, the neck was over here and the mouthpiece was in a little compartment over here and the ligature and you had to get the reed. I didn’t know even how to put it together. I couldn’t make a sound. She said "Oh, Mitchell's son plays the saxophone. Well that was only about three blocks from where we live now. So we went around to where Tony lived and he happened to be home. And I showed him the saxophone and he says, oh, you know, he showed me how to put it together. And he said "Play something." I said "I don't know how to play." So I remember he put on a recording by Duke Ellington and he took my horn and he put the reed on the ligature and the mouthpiece and he began to play with the recording, Duke Ellington's recording that was playing. And it was called "Cottontail". And he was playing my horn, with Duke Ellington and I was listening to it. And I was saying, "That's the sound of my horn." And that's how it began.

Cottontail up and hot

Benny Golson: I knew how to read music but I didn’t know how to apply it to the saxophone. So she had bought it at Wurlitzer's downtown, you know, where you pay a dollar down and a dollar all week for the rest of your life <Laughs>. So they had teachers there and you could get a block of lessons, 10 lessons. You get them in advance, pay for them in advance and you go each week. And I happen to have a teacher who used to be a saxophone player with Charlie Barnett. His claim to fame was he recorded "Cherokee", Charlie Barnett. And he decided he wanted to come off the road and come home. So he became a teacher down there and he was my teacher. Best thing that ever happened to me, because he taught me all sorts of stuff that really put me in good stead, Raymond Ziegler. Yeah, he's gone now. But he got me started. And that Earl Theater where I first heard Lionel Hampton, was just one block from Wurlitzer's. And as years went by, don't you know, I played the Earl Theater and he came to see me <Laughs>.

Jo Reed: Oh that's neat. We have to talk about your great childhood friend John Coltrane another great saxophonist and--

Benny Golson: <Laughs> Yeah, John, everybody knows him for his greatness. But we did not start out great. I met John when I was 16. I think he was about 18 and of course I used to practice-- when I first got my horn, it was in summertime and I used to practice in the living room, right on the front of the house. And the windows were up but the screen's in and so everybody could hear me playing and the neighbors wanted to kill me. Well I met him and he joined me and they wanted to kill two people <Laughs>, but we both got better, you know. And we got hired in this big band, big local band, Jimmy Johnson and His Ambassadors. John was still playing alto then and I was playing tenor. And we thought we were doing quite well. I was still in high school. By then I was 16, he was 18, yeah. And the jobs were usually on the weekend, Friday, Saturday, maybe a Sunday, which was great for me because I was still in school. And we lived for those jobs. The music was corny but at least we felt that we were moving ahead to be hired and working in a big band playing the stock arrangements. And we had a solo, maybe four bars here, six bars here, not two choruses, anything like that you know. But it was okay, you know. It was a stepping stone to something better. And both of us got fired, we were playing so bad <Laughs>. They fired both of us. Oh I remembered we came back to my house and we were standing in my living room, so depressed. My mother saw us standing there. We were usually sitting there listening to 78 records. And my mother saw us standing there and all the pain, because we had just come back. They said that the job was cancelled and we went up there to find out that it wasn’t cancelled. They were playing with somebody else. So we came back to my house with that realization. And we were standing and I wanted to cry so bad. And I knew he wanted to cry. But we were too hip to cry in front of each other, you see. So my mother saw us in the pain and she came in the living room when we were just standing in the middle of the floor. And she put her arm around both of us and she squeezed us and she said, "Don't worry baby. Both of y'all will be so good, that one day they won't be able to afford you." And we didn’t believe it <Laughs>. But years later, we were playing the Newport Festival. He had just put his quartet together and he'd just recorded "My Favorite Things" on soprano and Art Farmer and I just put the jazz stuff together and recorded "Killer Joe". And we happened to be in the same tent warming up and he had his soprano and was playing and he was trying to find a reed and I had my horn trying to make sure everything was all right. All of a sudden he took his horn out of his mouth and he started laughing hilariously. And I said, "What?" He said "Remember what your mother told us, you know, about one day they won't be able to afford us?" I said "Yeah." He said, "Well those guys are still in Philadelphia and we're at Newport." And we laughed. Things change.

Jo Reed: They sure do. You know, you came into Jazz in this transitional moment. As you said, you were originally inspired by Lionel Hampton and then along came Charlie Parker and along came Dizzy Gillespie.

Benny Golson: That's right.

Jo Reed: Can you remember that shift?

Benny Golson: Oh I remember so well. We heard that Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were coming to town in a concert down at the concert hall. And we decided we were going to go. So we went that night, not knowing quite what to expect. And it was Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie And they began to play. And we heard things that we had never heard before. I'm talking about a good performance. It went beyond good. Things that we'd never heard before. And they played a Latin tune, the likes of which we'd never heard. And John and I were looking at each other and I said, sounds weird, because we'd been used to playing stock arrangements. But this was totally different. And John said, "Yeah, it sounds like snake music. You know, the little buy with the snake in the straw basket and he's playing and the snake is curling out of it. It sounded like that." I didn’t know what the heck he was talking about. I said, "Yeah." So they played this tune and this Latin sounding tune and they played an interlude and then they made a break and Charlie Parker filled the break in. Well usually the break was filled in with just two bars. He took four bars and played it double tempo. Well we were screaming like the Beatles groupies. You know, how the Beatles groupies used to do when they-- we were screaming. He was trying to climb up my body and I was grabbing him. We'd never heard anything like that in our lives. It was "A Night in Tunisia". We'd never heard that, never.

A Night in Tunisia up and hot

Benny Golson: So after the show performance, you know, we went back stage and you know, like kids do, we were getting autographs from everybody. We got Dizzy Gillespie's and Slam Stewart and the other guys. Charlie Parker was going out the door. So I said, "Mr. Parker's going out the door John, we've got to catch him." So we ran up Locust Street. It was downtown. And we caught up with him. And we said to him "Mr. Parker we want to get your autograph." He was going to a club. He'd finished the concert which was in the afternoon from about 4:00 to about 7:00 and then he was going to play at the club that night. So we said "Well can we walk along with you?" So he said, "Okay." And so John said-- John who was on his left said, "Can I carry your horn?" So he let him carry his horn and I was on the right. See John never did much talking. I was always the talker whenever we went out. So I'm going to get to the root of how is this guy playing this kind of stuff. So I had to get with all of my dumb questions that had nothing to do with what he was playing <Laughs>. What kind of horn do you play? And I was making a mental note of this. What kind of mouthpiece do you use? What brand of reed do you use? What number reed do you use? And I was cataloging this. I was going to get to the bottom of this. We're going to learn how to play like that. And we got to the club and we were too young to go in the club. So he took his horn and as he departed, he says "I'll be on the lookout for you kids. Keep up the good work." And he went upstairs. Now I had to go to school next day and they played from 9:00 until 2:00. I didn’t care what my mother said when I got home. We stayed there from 9:00 till 2:00 because we could hear them. They were on the second floor but we were standing on the first floor but we could hear them when they were playing. And as they were playing, we were saying, what if we could then learn to play like that? It was such an experience. We didn’t have much money then. We were in South Philadelphia and we lived in North Philadelphia. So we had to walk home of course. But on that walk home was like no other walk. We'd heard this music that got into our bodies, our psyche and we just dreamed with each other on the way home. Do you think we could do this? Maybe we could do this and that. How long will it take? Will the opportunity come? You know, that kind of talking. Then we got to where we lived. He went to east side. I went to the west side to where we lived. And we were together almost every day and I didn’t see him for about a week. I wondered what was wrong. I got a call and he said "Benny, did you try any of that stuff Mr. Parker was talking about, you know, the mouthpiece and the reed and everything?" I said, "Yeah." He said "Did anything happen?" I said, "No." He said, "Me either" <Laughs>. It was more than the reed and the mouthpiece <Laughs> stupid kids. But we caught on as time went by. It was incredible.

Jo Reed: When you started writing Benny, did you know this is what you wanted to do?

Benny Golson: Oh yeah. Oh yeah.

Jo Reed: It gave a different satisfaction than playing?

Benny Golson: Oh yeah, it's different. People ask me, which do you like the best, the saxophone or the writing?" I say I'm a musical bigamist. I like them both. I'm married to them both.

Jo Reed: Yeah, but it's a different satisfaction.

Benny Golson: A different satisfaction, yeah. One I'm there waiting in the maternity room with the writing. Other is spontaneous right there at the moment. And whatever you do, it's there and it's gone. The other, you can preserve it andyou can change it from a B Flat to a B Natural. You can reshape. But when you're playing, it's spontaneous, you can't change anything. What you say is that's it. But you can shape what you're doing as you write. That's one of the advantages. Yeah, it's two different worlds. And when I write, I don't think about the playing. When I play, I don't think about the writing.

Jo Reed: Miles Davis recording "Stablemates" was a real game changer for you in a lot of ways, wasn’t it?

Benny Golson: You said it. Yeah, he gave me status. He gave me believability, because Philly Joe joined Miles' group--Philly and I played together in a local group before all of that, you know. But Miles heard him and liked him and when he joined him, Hank Mobley was the tenor player. But Hank was recording for Blue Note Records during that time and he was pretty popular. And he was becoming very well known. So he decided maybe this is the time for him to go out on his own and begin doing his own thing. So he was going to leave Miles. And Miles loved the way Philly played. So he figured if he would ask Philly if he knew of a tenor player, it would be somebody of the same ilk. So he said, do you know of a tenor player in Philly? And Philly said, yeah. So Miles said "What's his name?" He said, "John Coltrane." So Miles was a little uncertain about it. He says, "I never heard of him. Can he play?" And Philly probably made the understatement of his life, because he simply said, "Mmm hmm." So John left our coterie of musicians because we used to have jam sessions all the time and he joined Miles. And so I saw him two weeks later on Columbia. We both lived in North Philly. I ran into him on Columbia Avenue, and I said, "John, how's it going with Miles?" He says, "It's going great." Because he hadn't learned the repertoire, what they were going to be playing. He said, "But he needs some tunes." He said, "Do you have any tunes?" I said, "Do I have any tunes?" That's all I had, tunes. So I had written this oddball tune. It was kind of a crazy tune, I thought. I said, "Maybe it's oddball enough he might like it." So I gave it to John, and it was "Stablemates." I didn't think anymore about it. Nobody ever recorded anything of mine.

Stablemates up and hot

And I ran into him about a month later and he said, "Benny, you know that tune you gave me?" I said, "Yeah." He said, "We recorded it." I said, "What?" He said, "Yeah." I said, "Miles recorded my tune?" He said, "Yeah, he dug it." When I saw Miles, Miles said to me, "What were you smoking when you wrote that?" <laughs> Yeah.

Benny Golson: That's what got me started as a-- not as a saxophone player-- as a jazz composer. Yeah. That was the one. And now they play that tune everywhere. Everywhere I go, they play that tune. It's incredible. You never know what's going to happen when you sit down to write. If you did, you'd say, "Well, I think I'll write a hit tune today."

Jo Reed: Every day.

Benny Golson: Yeah, there is no such thing. And what decides-- I don't decide. The audience, the people here, decide, by the CDs that they buy, the money they plump down to come and hear you play it. They decide. It's all about the number of people who pay to hear it and buy what you play. That's what decides.

Jo Reed: Well, you played with Dizzy Gillespie in the mid '50s, What did you learn playing with Dizzy Gillespie?

Benny Golson: I learned a number of things. I learned how to pace yourself. If you try to play at the top all the time, high and fast, you got nowhere else to go. You have to learn to pace it. I learned that space sometimes is as important as the notes, if you place it strategically. And what space accomplishes--I'm not talking about a minute--just a moment or two. Space, what it accomplishes, it gives the audience a chance to, in a microcosm, in a microsecond, to reflect on what you have just played and to anticipate what you're going to play, which creates an element of anticipation, which is good, that space. Just to take a breath and not wall-to-wall notes, not a complete tapestry. And if the drummer's good, when you take that breath, he's going to do something to set you up for the next time you utter a sound musically.

Jo Reed: You also say you learned a lot from Art Blakey when you played with him and the Jazz Messengers.

Benny Golson: Yes, yes. Not notes, but attitudes and aggressiveness, and playing with fire. When I joined him, I was playing soft and mellow and smooth. It didn't work. It didn't work. We were playing somewhere-- Café Bohemia, I think it was, in the Village--and he would play these drum rolls going into the next chorus, and they were so smooth, it was like tissue paper, loud-- <makes drum roll sound>-- set you up for the next chorus. And he would do that, but when he would do it, nobody could hear me. And one night, he didn't give the two bars, he gave me a four-bar going into it, and he got overly loud. I mean, I was pantomiming. And when he came down on the new chorus, he came down with a crash-- "Crash!" And then another two or three beats, he gave me another crash. And then in another two or three beats, he gave me another crash. I said, "What is he doing?" And he hollered over at me, "Get up out of that hole!" <laughs> And that's what changed me. I said, "I guess I am in a hole. I have to learn to play more aggressively," not just on one low level all the time. And I happened to mention it to Freddie Hubbard. He said, "You too?" The same thing happened to him. <chuckles> Yeah, incredible.

Jo Reed: Now, you ended up really managing that band.

Benny Golson: Yeah. He trusted me. Yeah. Somehow, he trusted me. I can't understand all that stuff, because I was a greenhorn . Nobody really knew who I was. But I think what might have gotten his attention is this. <laughs> I went in as a sub. I didn't go in as a member of the band. And I had the temerity to tell him, "Art"--and somehow I knew he wasn't getting a lot of money when he was playing-- I said, "You should be a millionaire." I think that got his attention. I said, "The way you play, you should be a millionaire. Have you been to Europe?" He said, "No." I said, "You should be all over Europe." And then he looked at me with those sad cow eyes, and he asked me something that I never would have believed that would come from an artist like Art Blakey. He looked at me and said, "Can you help me?" And I don't believe what I said to him in return. I said, "Yes, if you do everything I tell you." And he said to me, "What do I do?" <laughing> I said, "Get a new band." And that's when we got Lee Morgan, Bobby Timmons, Jymie Merritt. And then I told him, "Art, when you play, you're playing a drum solo at the end of the tune like every other drummer. You got to play something where you start playing up in front and let the people know that you're the leader." I said, "Remember what you did on Straight, No Chaser with Monk? That started with you. You start with the right hand, then the left hand, and then the bass drum, and then the high hat, and you had four different things going at the same time. Remarkable. And then "Straight, No Chaser" began, the name of the tune. I said, "We need something like that to garner attention." And then I-- we were sitting somewhere in the restaurant talking. I said, "You played everything there is to play, Art." Then I think-- "Ah." I said, "Except a march." Then he looked at me, said, "You got to be kidding. Nobody plays a march in jazz. Except when you're going to a funeral in New Orleans." I said, "No, I'm not talking about the typical military march." I said, "Have you ever heard that college in the south? A black college, Grambling." I said, "Have you ever heard them play marches?" I said, "When they play their marches, the marches are dirty and greasy and funky." I said, "I'm talking about that kind of a march." He said, "Golson"-- he never did call me Benny-- "Golson, it'll never work." I said, "Well, let me go home and try." "Golson, it's not going to--" I said, "Well, let me try." "All right." We were working at Smalls' Paradise then, up in Harlem. I went home that night and I said, "A march." Then I start thinking. But it needs a melody." And that's when I started. I put this melody together. And so I called a rehearsal the next day, and I said, "Okay, Art, you're going to start this." He said, "Well, how long do I play?" I said, "Play as long as you want." He said, "Well, how will you and Lee know when to come in?" I said, "Play a roll-off." He said, "What's a roll-off?" I couldn't play on the drums, so I had to do it with my mouth. I said, "Play this." <mimics a roll-off> He said, "Oh, Golson, this is not going to work." I said, "Art, just try it....

Blues March up and under

Benny Golson: ...And try to make it sound like a kind of hip military thing when you're playing your solo up in front." And so he did. And I said, "Okay." If you've ever seen me perform, you know I like to talk. That night I gave it a big buildup-- Smalls' Paradise. I said, "Ladies and gentlemen, we're going to play a tune now that you would not expect to hear from a jazz group, and it's going to feature our leader on the drums." I said, "It's a march, but it's a different kind of a march," and I went on and on. Now, there was no dancing in this club, and as the patrons sat down, they had a small table, just enough for their drinks, one of those kind of things, but not room for dancing. We started "Blues March," and we got into it, and Art added that kind of a backbeat, almost like a rock and roll thing, and that's almost a shuffle thing. And boy, the heads were bobbin' and the people were moving. And after a while, they got up and started dancing and knocking their drinks over. And he looked over at me and said, "I'll be so-and-so." He didn't believe it. And he played that with every band that he had had to play "Blues March" and "Along Came Betty."

Jo Reed: You didn't write "Moanin'"...

Benny Golson: No, no, no. Bobby Timmons wrote that.

Jo Reed: But you were pretty instrumental in making it happen.

Benny Golson: Oh, he thought it was nothing. Oh, yeah, he, Bobby had-- he had this little lick he used to play between tunes. We'd finish a tune, and before we'd go to the next tune <mimics lick>-- and then he'd finish and he'd say, "Boy, it sure is funky." He did that for a while, a few weeks. And I thought, "You know what? That's eight bars, that's sixteen bars, and that's the last eight bars. Now, if he had a bridge to that, that would be a song." So we got to Columbus, Ohio, and I called a rehearsal. And we had all the music down. They were, "Well, what are we going to rehearse? We have everything down. Well, what are we going to do?" I said, "Bobby, you know that thing you play, Bobby?" I said, "If you put an eight-bar bridge there, you got a complete song." He says, "Oh, that's nothing. This is nothing." I said, "Bobby, that's a good tune there." I said, "We're going to go sit over here and you go up on the bandstand"-- because nobody was in the club-- "and write a bridge." About a half hour, he put something together, and he played it for me. And I said, "Oh, Bobby, no. That's not it, Bobby. That's not the same flavor as the lick that you're playing." He said, "Well, you write it." I said, "No, Bobby. This has got to be your tune. Just go back, and just try to make it like <mimics tune>-- get that same flavor for the bridge." So we went back. Twenty minutes, he called me, and he didn't think much. He said, "Well, here it is," like, "This is nothing." And he played it. I said, "That's it. That's it. Come on, fellas, let's learn it." And so we played it. I said, "Now, tonight, the audience is going to tell us what they think about this tune." So again, I announced it and brought special attention to it.

"Moanin’" up

Jo Reed: Now, how did you and Art Farmer get together to form the Jazztet?

Benny Golson: I met Art Farmer when I joined Lionel Hampton in 1953. And I got a chance to hear Art, and he had such a beautiful sound. His trumpet sound was fantastic. And we'd play together during that time. And then I eventually left Lionel Hampton and he did too, and so we were back in New York, and we were doing record dates here and there, and we became good friends. And I used to use him as my contractor, so whenever I got something-- a TV commercial, whatever-- I'd call him to get the musicians, and pay him as a contractor, and the trumpet player. And we were doing that, and I decided, "You know, there are lots of quartets and quintets playing, but very few sextets, those three horns. Why don't put something together, and with that extra horn, having those three voices, I could do things that I can't do with the two horns." So I said, "Who would be my trumpet player? Art Farmer." I called him up. I said, "Art, I'm thinking about putting a sextet together and I want you to be my trumpet player." He started laughing. I said, "Why are you laughing?" He said, "You're not going to believe this. I was thinking about putting a sextet together too, and I was going to call you to be my tenor player." <laughs> I said, "Well, come on by the house, and let's talk." So, yeah. So he hired the drummer, Dave Bailey, because they used to play together with Gerry Mulligan, and his twin brother, whom I used to confuse with him, on bass, Addison Farmer. I hired Curtis Fuller and brought a young unknown out of Philadelphia named McCoy Tyner as our piano player. And that was the original Jazztet. And that's how it happened. Now, the name, we couldn't get a name. And Curtis Fuller, he's so clever with words and things. Instead of a sextet, he said, "Just call it the Jazztet." That was it.

Jo Reed: Benny, why the move to L.A.?

Benny Golson: I wanted to write for the movies. Yeah. Because I'd been studying these advanced techniques with a fellow called Henry Brant, who was the one who orchestrated-- remember Cleopatra, with Elizabeth Taylor? He was the one who orchestrated that film for Alex North. And Spartacus-- he orchestrated that. He was my teacher, and boy, he taught me so much stuff, stuff that I couldn't-- the length and breadth of it that I couldn't use with writing something for Count Basie. It wasn't that kind of thing-- symmetrical chords and diatonic writing, and mirror writing, and stuff like that. I could never use for-- only place I could use it would be in Hollywood.

Jo Reed: You've written over 300 compositions easily. Do you think your melodies have a distinct sound? Is there something that makes a Benny Golson tune a Benny Golson tune?

Benny Golson: Well, the key word you used was melody. I love melodies. That's why I love Chopin and Brahms and some of the others-- Puccini. Oh, I love Puccini. Oh, those operas. Melody. Even if it's a fast tune, to me, I feel it should have some melodic content, something that you can go away humming, rather than just calisthenics and athleticism-- something that you can grab a hold to, something you can remember. My favorite thing if I sit down to write is a ballad. I like beauty. And my inspiration-- people say, "What's your inspiration?" Many things. Children at play. Something in nature. And a lot of it, my wife, Bobbi Golson. A lot of it's her.

Jo Reed: You put the saxophone down for a good long time.

Benny Golson: Oh yeah. I didn't play it. I didn't play the saxophone for, oh, I guess about six years. I said, "Oh, I played all I'm going to play on the saxophone. I'm just going to write now." And then lo and behold, I got the itch again, picked it up. And it was like getting over a stroke, coming back. It took me a year before I could feel halfway comfortable.

Jo Reed: Now, what was it like when you came back to performing after that long time of not?

Benny Golson: Some nights I felt at the end of the night, when people were patting me on the back, I felt like going to the microphone and apologizing. Felt like apologizing, because I, I stopped playing-- it was easy for me to stop playing because I didn't like what I was playing. I didn't know what I wanted to play when I wanted to write. But when I came back, a strange thing had happened. I wasn't playing the way I was playing when I stopped. The thinking process must have been going on, but I never put it to practice. But it still wasn't what I wanted to do. I was just going through a period, and it wasn't working. It wasn't satisfying me, so I know it wasn't satisfying anybody else. And today I guess I'm not thoroughly satisfied. I don't guess one is every really totally satisfied. There's a danger in becoming too satisfied, I think, because then you level off and the ship sails off as you're falling overboard, you know? <chuckles>

Jo Reed: Looking back at your career, I see how important mentors played at various points.

Benny Golson: Oh yeah. Oh yeah. I didn't--I don't know everything, and I don't know everything today.

Jo Reed: Now that you're a mentor, what do you want to impart to your students?

Benny Golson: Keep an open mind, and weigh everything carefully. Don't discard anything until you know what it's about. And don't ever be-- don't ever be satisfied with yourself. You can settle down into obscurity. There's always something new to learn, believe me, and no one person knows it all. Never be satisfied. That's dangerous.

Jo Reed: Benny Golson, you are a national treasure. You really are.

Benny Golson: Oh, I don't know if I believe that. I know when I go home, my wife's going to tell me, "Put the trash out."

Jo Reed: Yeah, I know, but that's okay. Both things can be true.

Benny Golson: Thank you. Thank you so much.

Jo Reed: Thank you. Thank you for everything, truly. Thank you.

That was composer and tenor saxophonist, Benny Golson

You’ve been listening to artworks produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the musical supervisor.

Excerpt from "Flying Home" composed and performed by Lionel Hampton from the album Flying Home used courtesy of LRC Limited and GrooveMerchant Records.

Excerpt from "Cotton Tail" composed by Duke Ellington and performed by Duke Ellington and his great Orchestra from the album The Essential Duke Ellington, used courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment.

Excerpt of "A Night in Tunisia" composed by Dizzy Gillespie, Jon Hendricks and Frank Paparelli, performed by Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker from the album Town Hall, New York City, June 22, 1945, used courtesy of Uptown Records.

Excerpt from "Stablemates" composed by Benny Golson and performed by the New Miles Davis Quintet from the album Miles: The New Miles Davis Quintet, used courtesy of the Concord Music Group.

Excerpts from "Stablemates" performed by Benny Golson and the the Philadelphians, used courtesy of Blue Note Records / EMI.

Excerpt from "Blues March" composed by Benny Golson and performed by Benny Golson and the Philadelphians, used courtesy of Blue Note Records / EMI.

Excerpt of "Moanin'" composed by Bobby Timmons and performed by Benny Golson and the Philadelphians, used courtesy of Blue Note Records / EMI.

The Art Works podcast is posted every Thursday at www.arts.gov. And now you subscribe to Art Works at iTunes U -- just click on the iTunes link on our podcast page.

Next week, poet and dramatist Claudia Rankine.

To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.