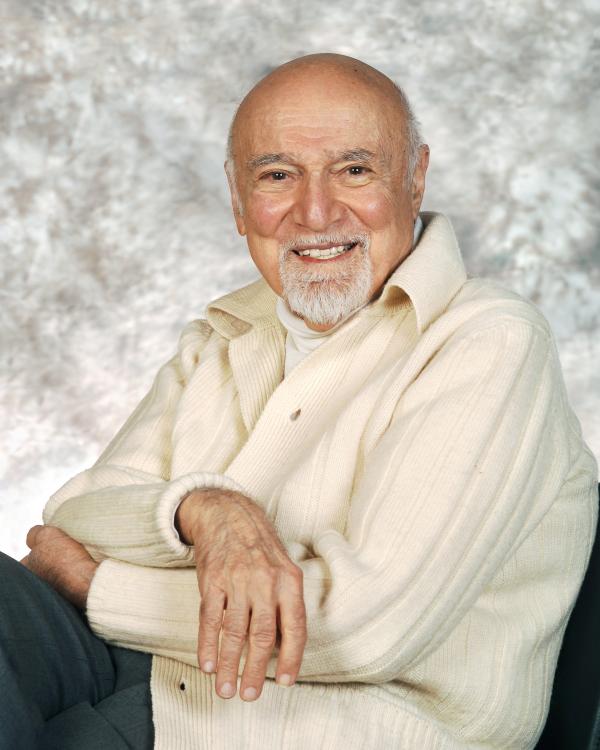

George Avakian

Photo by Tom Pich

Bio

"To receive a 2010 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master Fellowship Award is a culminating honor that confirms my long-held belief: Live long enough, stay out of jail, and you'll never know what might happen!"

George Avakian—recipient of the 2010 A.B. Spellman NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship for Jazz Advocacy—is a record producer and industry executive known particularly for his production of jazz and popular albums at Columbia Records, including the first regular series of reissues of jazz albums. In 1948, he helped establish the 33 1/3-rpm LP as the primary format for popular music.

Avakian was born in Russia to Armenian parents, who moved the family to New York City in the early 1920s. In his teens he became enamored of jazz through radio programs such as Let's Dance with Benny Goodman. While a student at Yale University, Avakian convinced Decca Records to let him produce a 78-rpm record of Eddie Condon, Pee Wee Russell, and others from the 1920s jazz scene in Chicago. Entitled Chicago Jazz, the recordings marked the first time jazz songs were produced in an album format rather than as singles.

In 1940, he was asked by Columbia to produce the industry's first annotated reissue album series, called Hot Jazz Classics, which included seminal out-of-print selections from Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, Bix Beiderbecke, Fletcher Henderson, and Duke Ellington. He included the first-ever unreleased and alternate takes in the series. In effect, he had created the first history of jazz on records.

After service in the U.S. Army during World War II, Avakian began his 12-year tenure as a Columbia Records executive, eventually presiding over its Popular Music and International Divisions. At the same time, he was acquiring a reputation as a jazz researcher and critic of some renown, having pieces printed in Tempo, DownBeat, Metronome, Mademoiselle, Pic, and the New York Times. Concerned about the lack of jazz education, in 1946 Avakian started a course in jazz history at the university level at New York University.

In 1948, Avakian introduced the LP record format created by Columbia engineers and produced the industry's first 100 long-playing discs of popular music and jazz. Two years later, he released the original 1938 recording of Benny Goodman's Carnegie Hall concert -- one of the first jazz albums to sell more than a million copies. This inspired him to use the long-play format for something new -- the live recording.

From 1959 onward, Avakian served as producer at Warner Brothers, World Pacific, RCA Victor, and Atlantic, among others. During the early 1960s, Avakian branched out, becoming the manager of Charles Lloyd and later of Keith Jarrett.

He has received a knighthood from the Knights of Malta (1984); the former Soviet Union's highest decoration (the Order of Lenin (1990)); a Lifetime Achievement Award from DownBeat magazine (2000); and Europe's prestigious jazz award, the Django d'Or (2006). In 2008, France bestowed on him the rank of Commandeur des Arts et Lettres, and in 2009 he received the Trustees Award from the National Association of Recording Arts and Sciences for contributions to the music industry worldwide.

Selected Discography

Louis Armstrong, Plays W. C. Handy, Columbia, 1954

Duke Ellington, Ellington at Newport, Columbia, 1956

Miles Davis and Gil Evans, Miles Ahead, Columbia, 1957

Benny Goodman, In Moscow, RCA Victor, 1962

Sonny Rollins, Our Man in Jazz, RCA Victor, 1962-63

Interview by Molly Murphy for the NEA

July 23, 2009

Edited by Don Ball

FAMILY HISTORY

NEA: Could you tell us a bit about your family's history?

George Avakian: My father's family had lived for well over a hundred years in the western part of Iran, which used to be Armenia until the Persians took over it. And the family business was wiped out when the Turkish armies came through the western part of Iran to attack the Caucuses. And so they fled, obviously because the village was virtually wiped out by the Turks, being an Armenian village.

And the result was that they were living hand-to-mouth, the whole family, in southern Russia. But there was a Persian gentleman who was the family company's best customer, who owed quite a lot of money but couldn't pay it because of currency restrictions during and after the war. So he sent 92 bales of Persian carpets to New York City to be held at the Guarantee Trust Company until a member of the Avakian family could come and prove that he was a representative of the ownership of the carpets. My father was sent by his older brothers in 1921.

NEA: Did you grow up speaking Armenian?

George Avakian: Well, I spoke Armenian and Russian, and my parents decided that the children should continue to speak Armenian but forget Russian, for various reasons.

Mostly they believed strongly that we must learn English in order to get along in the United States. And as a result, the language began to fascinate me when I was a kid. And I remember very well beginning to read books in the library after I'd gone into the first grade or kindergarten, I can't remember which. And, in fact, I remember the first book that I got excited about was a slim volume which the librarian told me I that I could follow up with another book by the same person.

And on my third visit I said, "Did this man write any more stories like this? " and she said, "Yes, comes with me." She took me to the back and on the shelf there was a huge volume so big that I almost couldn't carry it and it was the Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle. You know, the Sherlock Holmes stories introduced me to the English language in a remarkably strong way and this interest kept right on into high school when I discovered Shakespeare and so forth.

INTRODUCTION TO JAZZ

NEA: When did you first discover jazz?

George Avakian: [During high school,] one of the luckiest things of all, in terms of what followed in my career, was that I'd gotten interested in this strange music that I heard on the radio late at night, which reminded me a little bit of a folk music records that my parents had brought over -- the Armenian folk music: lively, peppy dances, and beautiful, nostalgic, sentimental melodies. I didn't realize that I was listening to a better class of American music, jazz. I didn't like what I heard on the radio, most of which was like "Yes, We Have No Bananas" and so forth.

I gradually discovered that it was people with strange names like Duke Ellington and Fats Waller and, of course, Louis Armstrong. I got very interested in the music that I heard on a program called Let's Dance, which featured three studio bands, one of them directed by Benny Goodman.

And when Goodman went on tour after the program stopped, he went onto the West Coast where the young people had heard him at seven o'clock in the evening instead of ten o'clock at night the way I did and he found that he was wildly popular. In fact, by the time he came back to New York in September of 1936, he was the bestselling artist on record. And I decided I am going to interview this man for the Horace Mann School newspaper, which I could do because I was the editor at that time. The problem was, how to do it? It turned out that one of my classmates had a mother who was on the Democratic Committee of New York City and she said the chairman owns the Hotel Pennsylvania where Benny Goodman is about to appear. Maybe she could set it up.

She did. Goodman consented to an interview. He liked the article that I wrote and told his right-hand man (he just had one employee in those days), "Anytime George and his friend Charlie want to come to hear the band, get them a good table." And it eventually reached the point where he also said that if your parents allow you to stay up late, come listen to the rehearsals on Saturday night after midnight because they would rehearse the new pop tunes of the day for the commercial program that they had, The Camel Caravan, on NBC. That relationship blossomed into getting to know these musicians and broadening my growing record collection, which really took a huge boost when another classmate sent the Goodman interview to his brother, who was a senior at Dartmouth and was a serious jazz record collector. And the brother said to his younger brother, "Ask George what he thinks of Louis Armstrong." Well, Julian Koenig was the young classmate.

He asked me and I said, "Well, he plays a lot of trumpet and he sings kind of funny, but I like him." The older brother, Lester Koenig, said to Julian, "Obviously, he hasn't heard the real Armstrong. Bring him to the house on the Saturday after Thanksgiving when I'm home. I'm going to knock his ears off." And he did by playing the Okeh records, the original Armstrong in 1920s and '30s, which were so totally out of print that I didn't know they existed.

I got wildly excited and said, "How can I get these? " They said, "Well, you can't find them. They're out of print." I said, "Who owns them? "He said, "The Brunswick Record Company." "Where are they? " "Oh, they're in the phone book. Write them a letter." Well, that started a campaign that went on for two or three years. No answers.

The big breakthrough for me was the good fortune of going to Yale because off campus there was a man named Marshall Stearns [who] gave his collection eventually to Rutgers University and established the Institute of Jazz Studies there. Marshall was going for a PhD in English literature. He graduated from Harvard. He was the foremost writer on jazz in the United States at the time and had the best record collection probably of anybody. And this small but remarkable collection was the keystone of an invitation he extended to me and another classmate, who, like myself, began to buy what we called "swing records" at the time, and said, "Every Friday night I have an open house. Anybody who wants to come and listen to records and talk about them is welcome."

Well, I spent virtually every Friday night at Marshall Stearns' listening to a complete history, known at the time, of jazz. This enabled me to not only get a picture of a whole history of jazz as recorded in the '20s and all, but Marshall asked me to cover a Battle of the Bands on New Year's Eve at Madison Square Garden between the Count Basie Orchestra and the Benny Goodman Orchestra.

Basie had become my great favorite by then. And I did. I was paid $6 and a six-cent airmail envelope sent to me by the editor of Tempo magazine in California and said, "If you write about more things like this, use this envelope and you'll get $6 again."

That started me as a jazz writer. And the development that finally nailed everything down was Marshall turning over his Collector's column to me so that I began to develop a reputation of being an expert you could ask questions of about"who played on this record" and all that, which I knew about through two sources.

One, of course, was Marshall himself, but before that Lester Koenig had told me on Thanksgiving weekend of 1936 that if I wanted to know more about this music there were no books that would help me in the United States. But since I took French at Horace Mann, he assumed that my French had to be pretty good, and he said, "Send an $8 money order to a shop in Paris, and ask them to send you Charles Delaunay's Hot Discography and Le Jazz Hot by Hugues Panassié." He said, The Panassié book will give you the story of great musicians and why they are great and also recommend records for listening. And the Delaunay book is the first book which cataloged personnel, dates, master numbers of important jazz records."

PRODUCING JAZZ

NEA: How did writing the column lead to producing jazz collections?

George Avakian: This enabled me to develop an idea that grew and grew during my freshman and sophomore years -- that jazz is something that should not just be on single discs, two-sided 78-rpm records that run three minutes apiece, no information except whatever is on the label. Jazz should be treated at length, the way opera and classical music is, and it should be annotated the same way, with stories of the background of the music, why it's interesting, why it's important. Well, I didn't get very far with letters to the record companies until almost out of the blue Decca Records, which had been putting out album collections, called. (By the way, I should say that albums were very unimportant in pop music, singles were everything. ) Decca pioneered emphasizing pop albums in the way of, let's say, assembling Bing Crosby's recordings of Hawaiian music when he made a film about Hawaii. This idea is what inspired me to suggest jazz should be treated in package form with a unified idea for each album and there should also be reissues of the great classic jazz, which is forgotten. Decca picked me up on the idea of packaging jazz. They said, "We've gotten this letter that you written. Come in, we want to talk about it."

The letter suggested that they start a series of jazz albums beginning with three albums, which would be attributed to the pioneers of jazz in New Orleans, Kansas City, and Chicago. I left out New York because I didn't like the New York jazz musicians particularly, except for let's say Bix Beiderbecke and people like that, who are really Midwesterners anyway. The upshot was that they told me, "Go ahead and produce these three albums as a start." I chose the Chicago album because that was easy.

The Chicago musicians were young teenagers hanging around King Oliver and Louis Armstrong and had moved to New York. That was the gang of guys known as the Austin High School Gang because that Austin High was where several students got together and began imitating what they heard of Armstrong and Oliver. That was Eddie Condon, Bud Freeman, Dave Tough, people like that. The album was completed and they said, "Now why don't you go on and do the next one? "

I said, "Wait a minute. I didn't ask you about getting paid and you haven't said anything yet." And Bob Stevens, who was the one I've been working with at Decca, said, "How about six bits? "Well, I'd finally realize it's cowboy slang for $75. But I spent more than $75 to go to Chicago to record a group with Jimmy McFarland. The plan that I'd use was three different groups representing the different aspects of early Chicago jazz. I thought to myself, "Well, here I am over my head. This isn't for me. If I ask for a hundred and fifty dollars, they'll give me a hundred dollars. It isn't worthwhile pursuing this." So, I said, "Okay," and I got a 12-page booklet -- the first one ever of the sort on jazz [included with the album]. And they said, "How about the rest of the of the plan? Who can record the Kansas City album, the New Orleans album? "I said, "That's easy. Give my notes to Dave Dexter," who was the hotshot crime reporter for the Kansas City Star and became the editor of Downbeat that year. He knows the jazz, he knows Kansas City. And Steve Smith to do the New Orleans part because he and his partner Bill Russell had explored New Orleans jazz before almost anyone else. And so, I thought to myself, "Okay, I've done the sensible thing, now concentrate on my studies."

But right away Columbia Records asked me to come and talk about the idea of program of jazz reissues. Obviously, they had seen the letters that I had written. So I went there and Mr. Wallerstein opened the meeting by saying, "We're here to discuss the idea of using this great catalog of out-of-print masters, which we have absorbed." A company called the American Record Corporation bought up these bankrupt companies, labels like OKeh, Columbia, and so forth. And they represented about two-thirds of all the popular records ever recorded in the United States. But they were just sitting there on the factory shelves.

Mr. Wallerstein turned to the factory management and said, "Mr. Morrison, would you read some of the letters that we received about this idea of reissuing jazz? "Mr. Morrison read one letter, paused, because there were six pages closely typed attached to the letter. I thought I'd better speak up. I said, "Mr. Morrison, I believe I wrote that letter." He looked and said, "Oh, so you did, two years ago." Mr. Wallerstein said, "Did you get an answer? "I said, "Yes, sir. The answer was that the publicity department in New York handles such matters and you will hear from them shortly." He said, "Did you hear from them? "I said, "No, sir." He said, "Well, you're hearing from me now." He hired me for $25 a week to come on Thursdays, because I had said I only had one class in the morning, go into the vaults, choose anything I wanted to reissue in the form of albums and single records, which would represent the history of jazz.

NEA: And you mentioned listening on those Friday nights with Marshall Stearns and other people. I think that's such an interesting experience to listen as a group to something and understand what other people are hearing.

George Avakian: Exactly, exactly. At this point I had quite a deep knowledge of what was available, and I was inspired to keep probing to the extent that when the war came along and the Hot Jazz Classic Series at Columbia was dropped because of the problem of the shellac supply (which was necessary to the manufacturer of 78 rpm discs) being cut off by the Japanese who invaded Malaysia. Ninety percent of the world's shellac came out of Malaysia. And of course I got drafted, went into the Army for four and a half years.

But I kept up with the music and the musicians. And in fact even produced another recording session for a friend of mine, Charles Edward Smith, who was one of the three authors of the best book that came out on jazz, the first really good one, called Jazzmen. Was asked by Moe Asch, who had a kind of a folk label, to produce a session with the daughter of W. C. Handy singing six of his songs.

Charles had never produced a record, but we had become good friends during my college weekends in Manhattan. And he said, "Can you help out? "I said "Sure." So I produced these sessions and Miss Handy, Katherine Handy, had a voice that was absolutely wrong for the blues. She was a trained soprano and she sounded so awkward singing those songs. But one of them was called "Chantez Les Bas," a beautiful melody that I didn't know about. And I resolved that if I ever produce any more recordings I'm going to produce "Chantez Les Bas" with Louis Armstrong.

In fact, that was the first idea of a whole album of W. C. Handy's music by Armstrong. There was no such thing as a W. C. Handy album in those days. In fact the only one that preceded the one I did at Columbia was the soundtrack counterpart album by Nat King Cole when he played the part of W. C. Handy in the film St. Louis Blues.

NEA: You know it's so interesting to hear you talk about that time back in the 1940s when you were feeling the significance of trying to document the music and preserve the history of the music. Of course now we think of pre-1940s or even in the '40s as being still the kind of beginning of jazz.

George Avakian: No, it really wasn't. And you're right about my carrying a torch for spreading the word about jazz because I got so excited about what a wonderful history this is and how good the music is. And that led directly to my having the opportunity to teach a jazz course at New York University when I got back out of the Army. And in order to do it, what was the text? The text was the recordings that I had reissued, literally. I followed that through for a number of years until it got to be a bit of a burden. Eventually Marshall Stearns himself came to New York City to teach at Hunter College and he took over the last stages of the course. And that's when he was inspired to donate his collection during his lifetime to start the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers.

The International Association for Jazz Education honored me and made a point of saying that I was the father of jazz education. I wasn't exactly, but the one that I started was the only one that continued for I guess about 10 or 12 years. And of course it petered out because NYU got into jazz studies as virtually every college did.

LONG PLAYING

NEA: Now you're also referred to as the father of the LP.

George Avakian: Well that's true. This was a case of being in the right place at the right time and knowing what to do. In fact I finally realized that if I ever finish writing this book that I've been sort of writing for 50 odd years, the title should be Right Place, Right Time.

When I came out of the Army I called Mr. Wallerstein because he had said, "When you come back from the Army, and if you want to work full-time in the record business, I'd love to speak to you." And I said, "Well it depends on my father. He wants me to go into the family business."

NEA: This is the carpet business?

George Avakian: Yes. When I came back I asked my father if it was all right to call him. He said "Sure, go ahead." Mr. Wallerstein immediately said, "What exactly did your father say? " He was an Old World person like my dad, a wonderful man. I said, "My father said, 'George you worked hard, got through Yale, went into the Army, came back in one piece, go ahead and enjoy yourself in the record business for a while, and when you want to be serious about life come into the family business,'" which I did 25 years later while still continuing as an artist manager and recording producer.

Mr. Wallerstein laughed and said, "Come see me Monday morning." And he hired me at $50 a week and I was the young apprentice in the A&R staff, which was not called A&R even then. And I was given all the schlock work that the older people, of which there were only three, didn't feel like doing. But I did get a chance to do things like a couple of Frank Sinatra sessions filling in for my immediate boss, Manny Sax, in which Sinatra kind of sneered when he saw me. Someone who was only, I guess, two or three years younger than he. He called me "kid." We got along all right, except that I realized this is an arrogant man and he's going to do just what he wants to do and I'm here to be a traffic director and that's it.

But two big things happened in 1947: Mr. Wallenstein told me, "George, start producing as many albums of pop music as you like, because our album catalog is very minimal and we think we can build it up." That was a nice thing to hear. He said, "You know the standard repertoire; Irving Berlin, Rodgers and Hart, and all that stuff. So start recording that music in album form."

Also the elderly gentleman who was in charge of the international department retired and Mr. Wallenstein said, "Why don't you do that. It's a very easy thing. All you have to do is keep in touch with EMI. They furnish masters of foreign recordings and there are a few foreign language artists like Frankie Yankovic and his Yanks, the Polka king, Italian singers, and so forth that you will record here, but it's very easy. You just record what they have in their repertoire and the repertoire can be something that you can find out about by speaking to the man who was in charge of the sales of the international department here in Bridgeport in New York."

I also got the reputation of having gotten the job as the only person in the New York office that spoke a foreign language, which happened to be true. Of course Armenian didn't help, but French and German I got to be pretty good at.

So here I was running these two very unimportant departments and, all of a sudden, Mr. Wallenstein came into my office and said, "I'm going to tell you something that you have to keep to yourself. We think that we can develop a process whereby we can record an entire album on two sides of a disk, 33 rpm." There were 33-rpm turntables at radio stations, so the basis of it already existed. I thought this was such a great idea because, among other things, I can record jazz at length instead of three minutes stop, three minutes stop. Which is really the right way to do it. One of the things that I resolved to do was to plan jazz albums, if this ever happened, on a basis far beyond just a collection of single records.

It came to pass that LP did come through. The program grew slowly because it took time for the public to buy the players that would make it possible. But by the time that we were able to expand the 10-inch LP, which was equal to the four pocket 78-rpm album, into 12 inches (which we felt should be the standard for pop music as well as for classical), the sales grew to such a degree that around 1953, 1954, certainly from 1955 and 1956, the long-playing pop record became much more important than the pop single. [However,] the emphasis on radio and in the trade journals continued to be the hit of the week kind of attitude, and the sales charts for single records were more important to the people in the business than album sales, partly because not that many companies were producing pop albums. They began to do it more and more as the market grew, but the smaller companies continued to just put out single records.

NEA: And what was the public reception to the LPs?

George Avakian: It was gigantic. It was so big that, by 1955, popular albums greatly outsold popular singles.

Now we had Mitch Miller making hot singles all the time, but those records cost 98 cents and the profit was relatively small. Whereas the long-playing record at $3. 98 represented more profit and you got a four-to-one ratio of income coming in from the sale of the albums. This was a wonderful feeling to realize that what I had started at a very small scale had blossomed into the most important part of the record business.

ELLINGTON AT NEWPORT

NEA: The LP offered the opportunity to be able to do live recordings, which is so wonderful in jazz and we didn't really talk about that. I wonder if you could maybe choose a session and tell me about the process of doing live recordings.

George Avakian: Sure. The idea of making long-playing live recordings was obviously something that I looked forward to, and the thing that was really the inspiration for it was the surfacing many years later of the acetates of Benny Goodman's Carnegie Hall concert which was the first million-selling recording album of course in the industry. I realized that there's an extra spark in many performances like that -- not every time but when it happens it happens big.

And the other aspect was to do something that was in front of an audience, which would possibly inspire the musicians to a higher level. The first time I recorded a jazz festival was in New Orleans in 1955 and the second was the Newport Jazz Festival of '56, which was a huge breakthrough to such a degree that people made a big fuss about it: "Oh, these are the first recordings ever made at a jazz festival." And I went right along with it and said, "Yeah, that's right because nobody paid attention to the first one, at the New Orleans Jazz Festival." And the major thing is Duke Ellington and the performance of "Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue," which was an accidental thing in terms of not having been planned. The Ellington appearance was to be highlighted by a new long composition dedicated to the Newport Festival. Ellington was more interested in his so-called serious long works than anything else, but they didn't sell on records. However, as a long-time friend of Ellington's and encourager of people who wanted to do offbeat things the way I did, I had recorded several of his compositions over the groans of the sales department. I called Duke and asked him if he could prepare a long composition for Newport in 1956. He said, "We don't really have something, but Billy Strayhorn and I are always working on things and we'll get something put together." I said, "I will ask George Wein if he will use some of my other artists and I will make a series of recordings at that festival."

That's exactly what happened, and the lucky thing was that Duke improvised an idea after he got to the festival. I believe he had it beforehand but hadn't told anybody about it. Duke called me on the first day of the Newport Jazz Festival and said, "George, we have a problem with the new work. It's still pretty ragged. We haven't been able to rehearse it properly but we're committed." He didn't want to disappoint the public and the press by not being able to record the work after it had been promoted as a highlight of the festival.

He said, "What can we do if there are mistakes? Can we prepare something? " I said, "Yeah, we can manage it." He said, "We're free on Monday after the festival, and the band will be relaxing at a hotel and if you book the studio, we can put some patches together and you can cover it up by various effects so it sounds as though it happened at the festival." I said, "It can be done."

I found out that we couldn't get the big studio. I said, "Look, we can use a small studio at 7th Avenue and with echo chambers and equalization. It'll blend just fine." So that was the plan. Ellington called the musicians together who had been goofing off as they so often do just before they went on and he made a little speech. I wish I had recorded it because we had the equipment there but I remember it very well. He told the musicians, "Let's not worry about mistakes on the new work. It hasn't been prepared adequately. We all know that. However, I've arranged with George that we can repair any passages that don't work out on Monday. He's got a studio reserved in case we need it. Billy Strayhorn is going to follow the score. He's going to mark everything that he hears that has to be repaired. And so let's do that and not worry about exactness and precision. And after that, let's just relax and have a good time. Let's do the 'Diminuendoand Crescendo in Blue. '"Then everybody kind of smiled and laughed and so forth, except Paul Gonsalves who was standing next to Duke. He said, "Gee I don't know that one." Everyone laughed because, as Duke said, "Paul that's the blues, you know. We change keys and then I bring you on. You blow a solo and I take you out. We change keys and we're out. You've done it before." And he said, "Oh, yes, yes, yes." But Gonsalves was a junkie. He was pretty much high during that time, but he was a professional. He came through it beautifully except for one thing. He blew into the wrong microphone.

Now we were recording at the same time as the Voice of America. The Voice of America had its own microphones and we had to depend on musicians who were being recorded blowing directly into our microphones, because we needed to have the sharpest sound, whereas the Voice of America was not so worried about exact sound. We started out by putting a white handkerchief or a rag of our microphones and telling each musician as they came up the steps and they would pass me, "Don't forget when you have to blow a solo blow into the microphone that has the white handkerchief." We eventually used white tape and everybody did that except Gonsalves, who simply went up there, screwed his eyes tight shut, and began blowing that fantastic solo. The first few bars were appalling because he was buried by the band and within a few seconds my assistant came running up the steps where I was at the side of the stage, and said, "What's going on? The engineer can't find him." I said, "Look, he's blowing off mic. Go tell him that we'll try to get his attention. Do the best he can." It was impossible to attract Gonsalves' attention.

Ellington yelled at him, and you could hear him yelling, but Paul never paid any attention. After the first chorus or so, the engineer was able to get the balance a little bit better. When Duke came off the stage the first thing he said, "How did it go? "And I said, "Well I think the suite is fine, a couple of mistakes, but not a problem." And Duke said, "Well you don't know the work. I do." There was quite a bit to be done. I said, "Duke, we'll do it." He said, "Well you just have to." And he said, "What about Paul? "I said, "Well I think we can manage that too." And Duke said, "Well I hope so because I don't know if we'll get a performance like that again." I said, "Well, Duke, it's a fantastic performance. We'll put all the possibilities of equipment onto the task of fixing it."

I think it was 28 choruses or something like that [that Paul Gonsalves played]. Anyway, so Duke told the musicians, "I'll call you around noon on Monday. Billy and I are going with George at nine o'clock to listen to the whole thing on tape and we'll know what to do." When it was finished, Strayhorn, who had stayed behind to help with the editing, took an acetate out to Duke. Duke called me up from somewhere in the Midwest, and his first words were, "Hi, George, I just have two things to tell you." And I thought, "Oh my God what are they going to be? "He said, "One is thank you and the other one is don't change a thing."

THE BRIDGE

NEA: What was it like recording Sonny Rollins for his legendary release, The Bridge?

George Avakian: Recording Sonny Rollins was a very interesting thing because Sonny and I had become friends just by chatting backstage as he appeared with the Max Roach-Clifford Brown group. I took a great liking to him because he was a person with interests well beyond music, and he was quite a philosopher.

Sonny retired from playing for a couple of years and was found by a jazz writer to be practicing at the upper reaches of the Williamsburg Bridge. I heard him at a club when he returned and realized that he was playing very, very well indeed. He was free at that point and I proposed that we record, and that the first recording would be called The Bridge and he should write a composition which would be appropriate. The publicity would be that Sonny Rollins has come down off the bridge and he is now bridging his past work to his present approach to music, which he developed while he was in semi-retirement.

So this friendship that developed resulted in his signing to record with me at RCA where I had gone after Warner. The project with Sonny was planned to relate Sonny to different aspects of the music that he had grown out of and had developed. And so each of the albums had a different theme. One of them, of course, was to have him perform with his hero Coleman Hawkins, which was something that he wanted to do because Hawkins was the first great tenor saxophonist of all. Sonny had told me that when he came back from Europe in 1939 I guess it was, one of the first things he did was to rush to hear him.

NEA: I was surprised to read somewhere that you felt that the recording Sonny meets Hawk wasn't quite what you hoped it might be.

George Avakian: Well, it was very good but what I was disappointed in was that each of them deferred to the other to a degree. I guess I thought they would challenge each other and so forth. Instead, both of them were kind of laid back during the recordings and it worked out all right, but I was hoping for a little more fire but that wasn't the way they were thinking. And after all who am I to push them in a direction that they didn't want to go? So it turned out very, very well but it was not the image that I had in mind.

I wish I'd followed up but at that point you have to realize that I was getting to be a tired guy. I had gone through building up the Columbia album catalog to a degree where it was the biggest income-producing unit in the industry worldwide. And then to help launch the Warner Brothers companies successfully was pretty tiring and then battling the conservatism at RCA was a little tiring also.

So I took it easy and just freelanced from then on. But I look back on all of that and I realize that in some ways the most important single thing that I ever did in the record industry was to change the emphasis of the industry in the direction of quality albums that would endure rather thanhits that came and disappeared. It was a kind of a dream that I had as a kid because I came to think of the recordings as program material not just three minute solos. And as a result there is something on a long-playing popular record for anybody who walks into a store and wants to have a particular kind of music or entertainment, spoken word, and so forth. That was the goal that I set myself at Columbia and it became something that was universal.