Elizabeth James-Perry (Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head, Aquinnah): NEA National Heritage Fellow Tribute (2023)

Roen Hufford: NEA National Heritage Fellowship Tribute Video (2023)

Joe DeLeon “Little Joe” Hernández: NEA National Heritage Fellowship Tribute Video (2023)

Michael A. Cummings: NEA National Heritage Fellowship Tribute Video (2023)

Ed Eugene Carriere (Suquamish): NEA National Heritage Fellowship Tribute Video (2023)

R.L. Boyce: National Heritage Fellowship Tribute Video

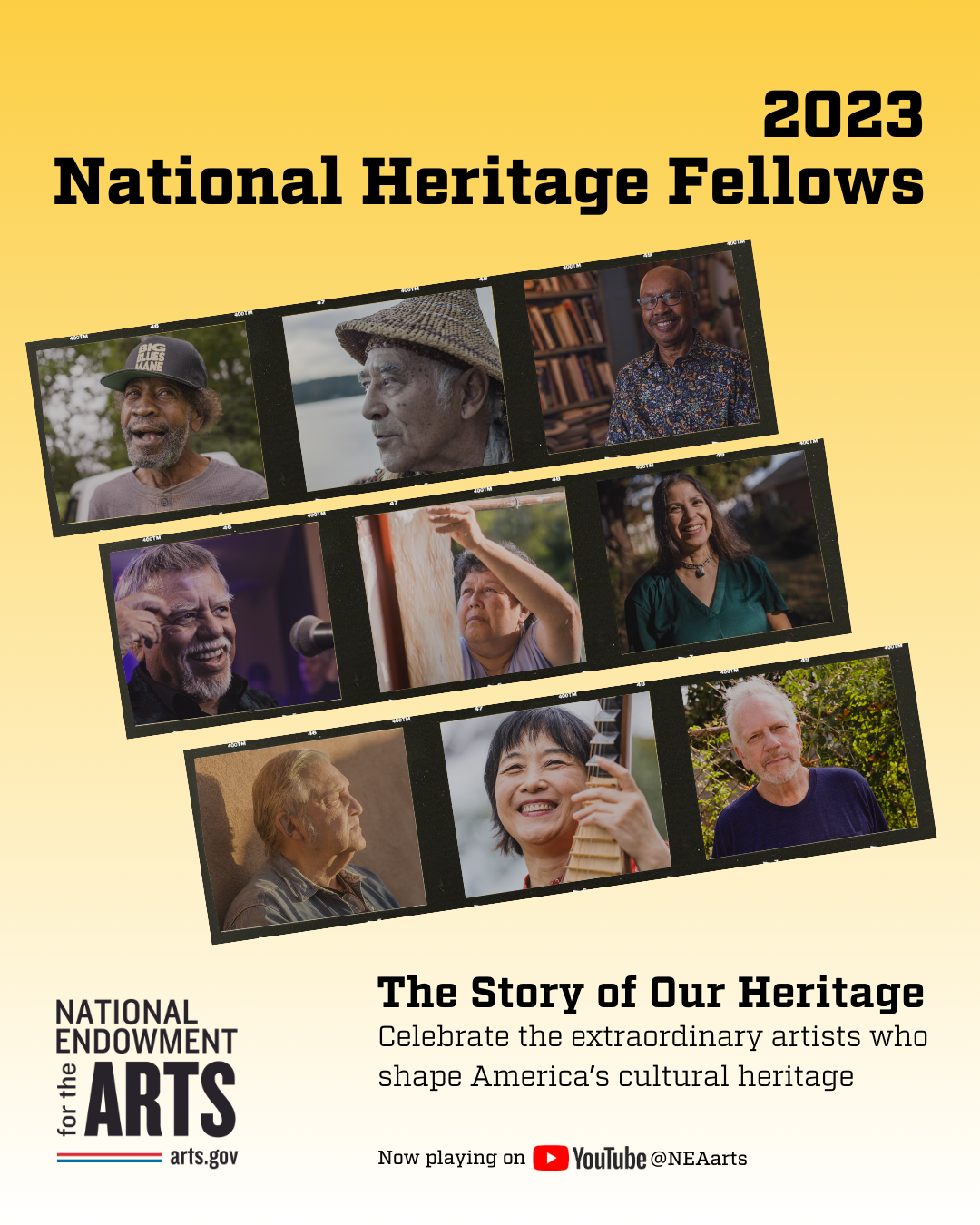

National Endowment for the Arts Premieres Tribute Film Series about National Heritage Fellows

Photos by Hypothetical

Psalmayene 24

Music Credits: “NY” composed and performed by Kosta T, from the cd Soul Sand; used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

Jo Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works, I’m Josephine Reed.

Today a conversation with Psalmayene 24, the award-winning director and playwright based in Washington D.C., whose work is noted for its thoughtful and innovative exploration of community, universality, and diversity. Playwright in residence at Mosaic Theater, Psalm’s work continually challenges and expands our understanding of narrative art. I’m a long-time fan always impressed with his unique artistic vision and commitment to storytelling which provides new perspectives on familiar and new tales alike. I was thrilled to be able to speak with him about his recent direction of the world premiere of Kia Corthron’s Tempestuous Elements at Arena Stage and his upcoming reimagining of Mary Zimmerman's adaptation of Metamorphosis at the Folger Theater. Psalm is a playwright, a director, and an actor, but he actually came to theater and performing through dance and that is where I began our conversation.

Psalmayene 24: Well, dance is actually the first artform that I remember doing and that I certainly fell in love with. I was the kid at the family parties who was just dancing up a storm in front of the adults, and with any other kids who were there. Growing up in New York City, I'm from Brooklyn originally, and I grew up while hip hop culture was emerging and was growing up itself. Dance was sort of my way of expressing my creativity in that artform, in the artform of hip hop. So, first and foremost, I mean, that's really actually even how I identify. I identify as a dancer first, and then all the other artforms followed suit after that.

Jo Reed: How did you move from dance to theater? When did that happen?

Psalmayene 24: That was really organic, because at one point I was actually a backup dancer for a hip hop group in Brooklyn, and we performed, and we performed on stages. Thinking about it now, that was a type of theater. I wasn't necessarily thinking of it as theater back then, but I'd say that was sort of, for me, how dance was really connected to performance. I studied both dance and acting in a more formal environment. I went to Howard and actually started out as a film production <laughs> major and then switched to dance and then switched to acting. So for me, the dance and theater have always been connected. I was part of the first wave of artists who were really focused on combining hip hop and theater together. So I was part of the first wave, that vanguard of artists who really focused on doing hip hop theater. So yeah, dance and acting and theater have always been sort of intimately connected for me.

Jo Reed: How did you expand to playwriting and directing?

Psalmayene 24: That was also very organic. I mean, I started out in theater proper as an actor, and then I really was not satisfied with the roles that I saw available for young Black men, so I decided to try my hand at playwriting. I said “Hey, I'll try to create some roles for myself that seem more appropriate,” and that seem more in line with how I saw myself and the way I felt about myself. Opportunities for playwriting started coming to me after that, and then I had gotten a commission to write a play from a theater in the DMV, a children's theater, Imagination Stage. The artistic director, Janet Stanford, asked me if I'd be interested in directing that play. It was called “Zomo the Rabbit: A Hip-Hop Creation Myth”, and I said “Yes.” I effectively became a <laughs> director after that.

Jo Reed: <laughs> And the rest is history, as they say.

Psalmayene 24: That's right.

Jo Reed: Well, you are the director, and you're the director of the world premiere of Kia Corthron's play, “Tempestuous Elements”, and it's at Arena Stage at the Fichandler. Can you give us just a brief overview of the play before we dig into it a little bit?

Psalmayene 24: Sure. So the play, “Tempestuous Elements”, really uplifts the legacy of Anna Julia Cooper. She is known as the mother of Black feminism, and she was a teacher. She was a writer, an orator, a poet, a playwright, so many things. But the play focuses on a few tumultuous years that she spent in Washington, D.C., while she was the principal of the M Street School, which was an all-Black high school that was focused on a classical curriculum. She was essentially fighting forces that wanted to alter that curriculum into a more vocational-leaning curriculum.

Jo Reed: She was part of a very powerful circle of Black women at the time, including Mary Church Terrell. It's interesting that Mary Church Terrell is so much better known than Anna Julia Cooper.

Psalmayene 24: Yeah, that is really interesting. I think one of the reasons might be because Anna Julia Cooper really spent a lot of her career as an educator, as a teacher. We know how this culture, how this society values teachers: not much. So <laughter>...

Jo Reed: Sad but true.

Psalmayene 24: Yeah. But I don't think that's going to last, especially, hopefully, after this play. I think a lot more people are going to know about her and know about her great legacy and just how important she was just as a thinker, as an early feminist. I mean, I like to call her a proto-intersectionalist. I mean, she was writing and thinking about what it means to be a Black woman in just a really high-level way, maybe earlier than anyone else in terms of the sophistication that she brought to what that experience means.

Jo Reed: Is that part of what attracted you to this project? What first drew you to this play?

Psalmayene 24: It is. I mean, first and foremost, Kia Corthron. I mean, her reputation as a writer is just massive. Kia really is one of our great playwrights. So, that's where it really starts. And then to think about shedding light on this person who I certainly hadn't heard of before I read the play, and then when I started to do my research about her and just found out just what a brilliant person and mind she was, I said “Well, yeah, this is definitely the type of story that I'm all about uplifting.” And then for it to be at Arena Stage, of course, one of our most legendary theaters in the country, and then for it to be in the Fichandler Theater, which is a theater-in-the-round, which is actually a theater-in-the-rectangle, but it's one of our most legendary stages in this country as well. All of those things, it's really an embarrassment of riches when it comes to being a director and to have the honor of being a part of telling this story.

Jo Reed: Well, you are very familiar with Arena Stage. You have a long history there. You were a master teaching artist there, and you were a director for their Voices of Now program. So, tell me about the Fichandler; what are the special challenges of staging a play when you have an audience on all sides of you?

Psalmayene 24: Yeah, it's almost like directing in four theaters at the same time. If you think about a traditional theater, which is typically a proscenium setup where you have audience on one side, performers on the other, you have audience on four sides. So you have to make sure that you're not privileging one side or another, north, south, east, and west. That's how they designate the sides in that theater. You have to make sure that all sides have an equally rich experience. There are some sound challenges that you have to make sure that you overcome with the cast. Even in terms of your scenic design, you have to make sure that whatever you're designing is not limiting or getting in the way of anybody in the audience. So yeah, there’re a bunch of sort of challenges and also a bunch of tricks of the trade to kind of help you overcome these challenges. So, I mean, I'm lucky to have seen literally dozens of plays in that theater, and that I have good friends and folks who I really trust, who I was able to kind of talk to about their experience working in that space, too. So I felt pretty well prepared, but it's certainly no easy job.

Jo Reed: What is it like, I have to ask you Psalm, approaching a play that hasn't been mounted? This is the world premiere. So you're the one who's going to give it a shape on the stage.

Psalmayene 24: Sure, yeah. I mean, that's, again, a thrilling challenge, because there is no blueprint. You're walking on terra incognita. You're going into outer space and you're the one who's going to discover the planet and figure out if it's habitable, or what have you. Certainly it's about finding the initial shape of it. I mean, the play was really receiving edits and changes very close to opening. All throughout previews we were making tweaks to the play and the script. But then, I mean, it's also such a great honor and pleasure because you have a hand in really shaping what hopefully generations of artists after you will be doing. You have a hand in really molding what that story will be. So yeah, it's just an honor.

Jo Reed: I have to imagine, because you're a playwright, you have to be very sensitive to what the playwright is saying and trying to portray and have a very diplomatic way of having discussions about that, I would only assume that?

Psalmayene 24: No, you're 100% correct. Always, whenever I had a suggestion or an idea, I would pretty much always say “But it's up to you. If you want to do it, consider this.” “Hey, let's try this. If we don't like it, we'll go back to what it was.” Because like you said, I mean, I've been in those shoes. I am in those shoes as a writer. So first and foremost, I want the playwright, in this case, Kia, to know that I respect what they're doing. I know how difficult it is and how challenging it can be. I mean, the playwright is the mother of the play, regardless of what gender you identify as, you're the mother of the play. I think the director is kind of like the father of the play, again, regardless of what gender you are. That's sort of how I look at the collaborative process between a playwright and a director.

Jo Reed: Do you see yourself as a very collaborative director? You're happy to take suggestions from actors?

Psalmayene 24: Absolutely, 100%. That's how I look at art. It's a democratic process. Ultimately, I'm the person who says “Yes, let's do it like this,” or “No, let's not do it like this.” But I want to hear all the ideas. I want to hear the bad ideas. I want to hear the great ideas. I mean, if I don't hear enough bad ideas, then I feel like maybe I haven't done something right to create an environment of safety in the room. I want all of my collaborators, actors, designers, stage management, I want us all to feel like we can throw out those really zany ideas. Because every now and again, those zany ideas might actually be strokes of genius.

Jo Reed: We talked about you sort of creating the footprint for this play, but the actors are too. <laughs> They have nothing they can look at that's happened previously. I'm thinking most particularly of Gina Daniels, who plays the role of Anna Julia Cooper. This is a long play with a lot of dialogue, and she is on the stage practically the entire play.

Psalmayene 24: Yeah, no, you're absolutely right. So the actors are in a similar position. They're creating these roles. Their impact on what these characters are to become cannot be understated. Yeah, Gina’s just incredible. I mean, what she does in this play is just astonishing. I was talking to her early on in rehearsals and I actually came on as the director for the second workshop of the play. They'd done one workshop actually the week that the world shut down. Right as the pandemic hit, they were doing the first workshop and that workshop got interrupted. But I came on for the second workshop and after just a few moments of hearing Gina speak these lines and really inhabit the character, I thought to myself “Oh, this is our Anna. We found her. We don't need to really go any further than this.” I mean, her instincts for Anna are just so spot on and she's got all the facilities, the grasp of language and the intelligence, and her demeanor and spirit, they’re just so right for a role like this.

Jo Reed: I think she also has something that I find so compelling in an actor, and that is the ability to be still on a stage and at the same time, your eyes can't leave her.

Psalmayene 24: Yes. I mean, that's just a testament to her experience, her craft, her skill. I mean, this is one of those times when just the right role meets the right actor, and everything just sings.

Jo Reed: “Tempestuous Elements” is part of Arena's Power Play series. Tell me a little bit about that series?

Psalmayene 24: Well, the Power Play series was created by Molly Smith, and she wanted to focus on different periods, different decades in American history. So she decided to commission-- I don't know if it's 20, but something close to that, playwrights to write plays focused on each of these different decades, really rooted and tethered to historical moments and figures who were important in American history. So, I mean, I think that Power Play series, that initiative is one of the great American theater initiatives. What vision, to really say “I'm going to investigate these decades and commission these playwrights to tell these American stories.”

Jo Reed: Well, you are next going to be directing Metamorphosis, Mary Zimmerman's play at the Folger, and that's opening in early May. Very different from <laughs> “Tempestuous Elements”.

Psalmayene 24: <laughs> Yes, it is.

Jo Reed: Tell me why you wanted to direct Metamorphosis.

Psalmayene 24: Wow. Well, the universality of the story really resonated with me. I mean, these are myths that are timeless, and that's the kind of work that I'm really attracted to. I had actually seen Arena Stage's production of Metamorphosis that Mary Zimmerman directed some years ago and really loved that production. And I was really interested in doing something different with that piece. So you know, between great material and then having an opportunity to really interpret it in a unique way, those two things really drew me to this production.

Jo Reed: Well, I'm curious, because with Tempestuous Elements, it was the world premiere, you're working with the playwright, you are literally creating the footprint on stage for that work. Metamorphosis, these stories are thousands of years old and adapted so famously by Mary Zimmerman. So I'm curious how that changes the way you literally approach the work.

Psalmayene 24: Yeah, great question. So well, you really have to think about what do I have to say through this piece that can illuminate a different feature that hasn't already been illuminated before? So in thinking about this piece, well, one, there's no pool in our production. So for those who are familiar with Metamorphosis, a pool is described in the script, and as far as I know, you know, most, if not all of the productions of this play have some sort of pool on stage. This production does not, and that was sort of a request from Karen Ann Daniels, the artistic director of Folger, who, in speaking to me about the piece in our early conversations, she said, “Well, you know, the building will just be undergoing major renovations and will just be opening. So it's probably not a good idea to have a pool on stage.”

Jo Reed: I hear that.

Psalmayene 24: Yeah, and I totally understood. And I actually embraced that and said, okay, well, now this is an opportunity to really do something different. So instead of water on stage, we are really infusing the production with movement. So I'm describing this production as a choreo drama. That's a term that's been used before, but it's appropriate for the approach that we'll be using for the show.

Jo Reed: I wonder how it changes the way you work with actors, because the actors, again, who you worked with in Tempestuous Elements, they're creating the parts.

Psalmayene 24: Yeah.

Jo Reed: These are actors who, obviously, it's Mary Zimmerman's adaptation and your vision, but these are myths that we've known about most of our lives.

Psalmayene 24: Yeah. Well, we're certainly putting a different spin on it. I'll say the ensemble that we're working with for this production is all Black. So I think that particular lens certainly informs character choices and how we may understand the stories. And I'll back up a little bit and say that when Karen Ann and I were sitting down and discussing potential ensemble composites, the idea of an all-Black ensemble came up. And at first, I was not on board with it. I didn't really understand why we would necessarily make that choice in 2024. And then the shooting killing of Tyre Nichols by Memphis police officers happened. And then in that instant, I knew, right, we have to do this production with an all-Black cast, because we must say something about Black humanity. Grief is what really drew me toward that decision as well. I fell into this sort of portal of grief after I heard about Tyre Nichols' killing. And then as I started to really think about the production, it really became and it really is a celebration and elevation of Black humanity. And also a celebration of culture from the African diaspora. So, while the impetus for this production is one that is tragic, I feel like ultimately it's moving towards sort of a triumphant vision for us all. Because while it's a production that's told through a very specific lens, the impulse is always to really say “Hey, we're all the same. All peoples are the same, and we've been the same since time immemorial.”

Jo Reed: I was just thinking that, because why have these myths lasted for thousands of years? Because there's a universality in them.

Psalmayene 24: Yeah, you get all the dualities of the human experience from love to animosity, greed to generosity, mortality and immortality, cruelty and compassion. And it goes on and on. The material, what Mary has created, it's just so rich in terms of the choices of the myths that she chose to include. And just the utter breadth of humanity that's on display is just really dazzling.

Jo Reed: And I would imagine having an all-Black cast really works with and also expands the storytelling and interpretation of Ovid's stories.

Psalmayene 24: That's exactly right. And it's not just about the Black artists, the Black people that we have on stage, but then in elements of design, like in terms of the costume design. Now there are a lot of opportunities to really explore the true richness of the African diaspora in terms of clothing, what people wear and prints and all of that. Of course, in terms of the sound design and music that's in the play, we're really exploring Black music all the way back to African music, to contemporary music as well. And you'll even see it in the scenic design, different architectural influences that are certainly African. So that love and embrace of Black culture and Blackness, again, going back to Mother Africa, is all throughout the play.

Jo Reed: So I imagine this is also carrying over into the choreography.

Psalmayene 24: Absolutely.

Jo Reed: And you're working with Tony Thomas, who you worked with in Tempestuous Elements. Can you just share anything about that process, the process of choreography and how it's working with the narrative?

Psalmayene 24: Sure. Well, I'd read somewhere that the director is the author of the action when it comes to plays. So while we have text that certainly inspires the movement in the play, too, we're thinking about ways that movement sort of can tell the story that this production is telling. So it's integrated throughout the piece in a way that's in harmony with water. While we don't have actual water on stage, water is such a prevalent metaphor in the play that we thought it made total sense for us to really let the movement sort of be born out of that connection to water. So that's where we started. And then we look for opportunities to organically infuse the piece with movement that is familiar to Black culture, movement that comes from Africa. And then just creative and original movement that makes sense for the storytelling that we want to do now. But it's certainly fluid to stick with the water metaphor, and the movement is threaded throughout the entire piece. So I'm really excited to actually see how audiences respond to the storytelling and specifically, not just the text, which is incredible, but to the moments where we just use movement in this production.

Jo Reed: Let me ask you this. Because I know you like to work collaboratively with the cast. So how do you create that, especially in a piece like this? Because choreography is fairly precise-- that encourages creativity and innovation and comfort more than anything during rehearsals?

Psalmayene 24: Yeah, great question. So our first week of rehearsals, along with our text work and table work, we did a series of improvisations that were movement-based, that were connected to the themes that are in the play. And some of those improvisations and movements that we discovered through those improvisations actually have found their way and ended up in the production itself. So this is really a process of seeing what works best with our ensemble, because these aren't dancers who act. These are actors who move. So we have to make sure that we're not overextending what we do in terms of what's set on them. And then I'll also say, in this production, we've gotten Mary's blessing to actually add a non-speaking character who is a water nymph-- the primary conveyor of water. So that's also how we addressed not only movement, but the metaphor of water in the play and production

Jo Reed: Last September, you had two plays that you wrote, Monumental Travesties at the Mosaic, and Out of the Vineyard at Joe's Movement Emporium. You've worked on “Tempestuous Elements”. You're working on “Metamorphosis”. You're playwright-in-residence at Mosaic Theater, where you've organized a massive project, the H Street Oral History Project. How do you keep everything straight?

Psalmayene 24: Oh my goodness. If you ask my wife, not very well. <laughter> But I mean, I just do my best. I mean, I do like to stay busy. I also like to recharge. I'm a big nature guy. I love going to Rock Creek Park and just taking walks on trails and things like that. But that downtime is really crucial for me. When the pandemic hit, that's when I really started going out into nature, and now that's really an important part of my artistic practice, making sure that I go out and commune with that larger, bigger force. But yeah, I do have a pretty good ability to focus in the moment and block everything else out. So I think that helps me, so that when I'm doing one thing, that's all that I'm doing, and I'm there like 199%. But yeah, I mean, I juggle it, and sometimes things fall, <laughs> you know what I mean? But I just pick them up and keep on juggling.

Jo Reed: I wonder as a playwright, what drives your writing?

Psalmayene 24: Oh man, love, certainly love. I mean, I love telling stories about the Black experience in particular, in a way that connects us to all of humanity, in a way that really reveals that we are part of one human people. That's the bigger overarching mission, if I have one. I mean, because I'm Black, I'm well-versed in a lot of aspects of the Black experience, but not all. I mean, the Black experience is so vast and so enormous, and there's always something to learn. That also drives me, knowing that there's a lot to learn about the Black experience. I'm always learning about new exciting people like Anna J. Cooper. I mean, didn't know about her, and was just really excited about that project. But projects like that, that excite me to shed light on the Black experience in some way.

Jo Reed: Right now, I read that you're working on a play about John Lewis.

Psalmayene 24: Yes. It’s a musical. Yes, and it's called “Young John Lewis”. It's focused on his younger years from about 15 to his mid-20s. I'm actually finishing up a draft now. I actually just wrote a new song yesterday for that musical. So that's really fresh. But yeah, I'm working on that with the theater down in Atlanta, Theatrical Outfit.

Jo Reed: Wow, that will be very exciting.

Psalmayene 24: Indeed, yeah. I mean, his voice is one of those evergreen voices, that it feels like we always need to hear his voice now, with his focus on peace and non-violent-direct action and community, I mean, really resonates during these times.

Jo Reed: Yeah, I agree. Thank you for doing it. Thank you for everything.

Psalmayene 24: Absolutely. My pleasure.

Jo Reed: And especially for giving me your time, I really appreciate it, Psalm, thank you.

Psalmayene 24: For sure. Thank you for having me.

Jo Reed: It's a richer city because you're in it.

Psalmayene 24: Thank you so much. I appreciate that.

Jo Reed: That was playwright and director Psalmayene 24. He recently directed Kia Corthron’s 'Tempestuous Elements' at Arena Stage. Metamorphosis, adapted by Mary Zimmerman and directed by Psalm, begins previews tonight May 7 at the Folger Theater and runs through June 16. We’ll have links to Psalm’s website as well as to both Arena Stage and the Folger in our show notes. You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating on Apple—it will help people to find us. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

A Message from the Chair on Holocaust Remembrance Day

Photo by Sixteen Miles Out via Unsplash