Art Talk with Disability Culture Activist and Community Performance Artist Petra Kuppers

Petra Kuppers, disability culture activist and community performance artist. Photo by Tamara Wade

Petra Kuppers, disability culture activist and community performance artist. Photo by Tamara Wade

Visitor viewing Aryel “Ariel” René Jackson’s A Welcoming Place, 2020-2022 (digital video, 29 minutes and 23 seconds). Photo by Alexandra Vanderhider

Music Credit: “NY,” composed and performed by Kosta T from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

Jo Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works, I’m Josephine Reed. Today, a special edition of Art Works—a conversation between the Chair of the National Endowment for the Arts Dr. Maria Rosario Jackson and the Director of the Census Bureau Robert Santos discussing the profound connection between the arts and science. It’s moderated by the Director of Research and Analysis here at the Arts Endowment Sunil Iyengar. In fact, it was Sunil’s brainchild. Now you or may not know that the NEA and the Census Bureau have a long history of working together in cultivating data sources such as surveys about arts participation. Sunil happened to be in a meeting, several months ago, with Chair Jackson and Director Rob Santos, and was impressed by how fluid their conversation was—moving from the arts to science to back again, and thought this would be a great podcast-- for others to hear first-hand how these two agency heads relate to each other, especially since working across federal agencies and departments has been a key priority of Chair Jackson’s. Happily, for us, they graciously agreed. And, the result is a far-ranging discussion that explores the intersection of arts, culture, and statistical science. So, here is the conversation between Chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, Dr. Maria Rosario Jackson and the Director of the Census Bureau Robert Santos, moderated by Sunil Iyengar who is the NEA’s director of research and analysis. Let’s listen.

Sunil Iyengar: Director Santos, it's really a great pleasure to get to speak with you and Chair Jackson. I was wondering, for over four decades now, we at the NEA have worked closely with the Census Bureau to track levels of arts participation throughout the country and really have your agency to thank for that. We've used census data to report statistics about artists and cultural workers and arts organizations. I was wondering, Director Santos, if you can tell us from your perspective, why the arts merit that kind of attention from the federal government's largest statistical agency? In fact, why this whole endeavor of scientific measurement being brought to the arts from your perspective?

Robert Santos: Well, thank you very much for that question and it's an honor to be here today with Chair Jackson having this little chat. The tracking of public participation in the arts and active engagement as artists is incredibly important from a societal perspective and that's part of the reason that we make sure to do our best to collect good quality data from the American public on their participation in arts. We need to know who we are as a country and it's the mission of the Census Bureau to provide the highest quality data on our nation's people and our economy and, by knowing a little bit about how we participate in the arts, we can get a fuller breadth and appreciation for how we engage not only with the arts itself, but with each other as human beings in our society. That allows us and helps us with other research that shows that participation in arts and enjoyment of arts actually helps our health, our well-being. That is really highly valuable when it comes time to take a look at other socioeconomic characteristics, our health issues, either mental or physical limitations, employment, unemployment, our situations. Because art, when you put it into the mix of all the other types of services that we can provide, really completes the holistic picture that we need in order to understand us better and for government to better serve us.

Sunil Iyengar: I really appreciate that. And we're truly grateful for this partnership with the Census Bureau and with you, Director Santos, and the chair of the NEA, Dr. Maria Rosario Jackson, herself has experience, rich experience with research, with data, and using that for the purpose of community engagement and so I wanted to, Dr. Jackson, you may have your own comments on what was just said by Director Santos, but I also wanted to ask you if you could speak a little bit about kind of in your prior life as a researcher, educator, writer, and consultant, to what extent did data, or even maybe census data, help you catalyze conversation with funders, developers, and policymakers?

Maria Rosario Jackson: Thanks, Sunil. Like Director Santos, I feel so honored to be in this conversation and be in this conversation with Director Santos and in the position that he's holding now, which is so important. I want to riff on something, Rob, that you said that I think is so poignant, and that is we need to know who we are as a country. And the Census, as an agency, as a practice, is such an important element of that quest to understand who we are as a country and I think that we, from so many different perches within federal government and beyond, we can't do our best work if we don't know what we're dealing with, if we don't know the conditions that people find themselves in, if we don't know about the demographics of our society and I'm so grateful that part of what the Census has devoted attention and resources to is some sense of understanding cultural participation in the United States, because that, too, is part of understanding who we are as a country. I was very grateful for that phrase, Rob, and I'm sure we'll come back to it in the conversation.

Robert Santos: Thank you very much, Maria. I totally agree, of course, and I look forward to our continued chat right now.

Sunil Iyengar: Well, Robert, it's funny because when you were talking, and I think we can hear the passion that you have for the mission of the Census Bureau and how it intersects with what we do at the NEA, I felt that there's something maybe lurking beneath the surface there in terms of your own interests in the arts, personally, and I'd love to hear more about that. I know Chair Jackson often talks about living artful lives, so it'd be great to hear what a top statistical official of the government does with the arts in their own time.

Robert Santos: Yeah, it's really interesting that Maria talked about leading artful lives, because I think that artful lives are essential to being the full human beings that we are, the full contributors to society that we are and, in my case and the case of many other social scientists, an artful life, I believe, is an accelerator to being even better scientists. I often engage in my own personal art--photography. I was a live music photographer for South by Southwest festivals in Austin, Texas, for eight years. And that was the most incredible experience because you not only were able to practice the art of photography with some amazing human beings who are fellow artists and fellow creatives, but also we were able to witness the richness of the artists that were performing and the richness of the artists that were speaking about how they went about doing things like writing songs or coming up with a movie script or creating a new vision of what gaming should be in the technology arena. But when it comes to science, being artful is essential for being a better scientist, because science itself, the innovation and the advancement, doesn't necessarily come from a mathematical formula or a test in a lab. It comes from this creative spark. The creative spark is what propels the ideas to create a hypothesis, like theory of relativity or quantum mechanics, that type of thing and then go out and gather information and then verify or revise the hypothesis. You're getting knowledge gain. Knowledge gain, to me, and science is very much tied into creativity, which is fueled by living an artful life and that's what I found through my experience being a photographer and also being a writer. I can talk about that later on if you want, because I've taken enough time describing some of these other things.

Maria Rosario Jackson: I think it's such an important observation to recognize that there's a connection. I mean, oftentimes you think of it as those two areas of study, of practice, of funding, of policymaking-- you think of them as completely separate when they're not and recognition that creativity has to be a part of science and that there's relevance there feels really important. It makes me think about the efforts to move from STEM to STEAM. From science, technology, engineering, and math to having the arts included in that and that feels like such an important progression. Rob's comments just make me more excited that there is energy around this concept of STEAM and not seeing the arts as separate from our endeavors related to science and technology.

Robert Santos: Thank you for that, Maria. I actually would like to give an example of how some of those things tie together. When I was a live-music photographer, I would be engaged in taking photographs. There would be other photographers assigned to the event, and they would be moving all around to get all these different lighting and perspectives and so forth for their own vision and I found that I ended up doing the same thing and they would come to me and say, “Why did you insist on taking a photo of this person where there's just a black background?” and then I'd show them the picture and they'd say, “oh my God, what a different perspective. Here we are chasing light and you embraced the darkness.” So I offered a different perspective and that added value and insight into the work that they were doing. But, see, that lesson applies equally in science as well and especially in work that's done by the Census Bureau in terms of surveys and the cultural relevance and such. What we found is that there is no one best way to ask a question. You really need to take into consideration who is it that you're asking? When is it that you're asking? So that one can tailor and get different approaches to capture the most relevant and accurate information, and none of that can happen unless you get these diverse perspectives from different types of individuals. So that's actually how I'm working with the Census Bureau as a leader to show an appreciation for allowing different perspectives before any decision is made and that includes perspectives from the community because those are really, really cogent, informative perspectives that bring in cultural lenses and bring in different types of values and life experiences that we really need in order to do a better job and all of that ties up into art.

Maria Rosario Jackson: This idea of diverse perspectives is really getting my attention because it's so central to different aspects of my career and even what I'm doing at the Arts Endowment as chair now. But to offer an example from an earlier part of my career, when I was teaching, I often taught students from public policy, public administration, arts administration, a number of majors, let's say, that at their best are in the business of creating healthy communities where people can thrive as professionals. This is what they aspire to do. And I would often provide an assignment for my students that was about getting to know a community and, of course, the census information was invaluable because that began to paint the picture of the demographics of a community. And I would always supplement that kind of a resource with other perspectives and other ways of knowing. One particular resource that I would turn to when we were looking at communities in the L.A. area, there's a neighborhood called the Watts-Willowbrook neighborhood in Los Angeles and it's an area that is known for being challenging. There is a high rate of poverty. There is evidence of crime and there are a lot of characteristics that often are painted as community deficits. And it just so happened that there was an artist that helped to lead a planning process in that neighborhood and part of the planning process included conducting an asset map and one thinks, “Are there assets in a community that is so challenged?” And the answer was “Yes,” and those assets were often cultural, and the way that the artist did it was through engaging with community members to better understand the things that they were passionate about, the things that they loved, the things that they were involved in from a creative perspective. They created these really beautiful videos and even a book about the cultural assets in this neighborhood and so when we would look at that neighborhood in class, I would offer what was available from census data, what was available from administrative sources at different scales, whether it was state data or more locally generated data and then I would also layer in this cultural asset mapping that had been led by an artist in collaboration with communities in order to come up with a more comprehensive and, frankly, a more humane understanding of who lives here and what do they care about? What are their aspirations? It really was an effort to get students to think in a more holistic way about how you come to know a place and a people. And I go back to what you said earlier, Rob: We need to know who we are as a country, we need to know who we are as communities, in order to do our best work in creating places where people can thrive.

Robert Santos: Hear, hear.

Sunil Iyengar: That's a great segue because I actually was wondering in all this, as we talk about the arts and how they can complement science and improve social science and statistics gathering, what Maria is talking about is also the creativity and, also, to a large extent, trust building, right? It's artists and culture bearers as trusted, not only messengers, but helping to collect that kind of information and do it in a way that resonates with community members. Rob, when you were talking about really how essential it is to reach out into these communities and engage with them directly and how artists can help with that, do you have any thoughts about, from your perch at the Census Bureau, how can artists be part of this conversation and really help to communicate with the population in a way really provides information that's of use to the Census Bureau, but also is authentic to communities? Do you see a role for artists as trusted messengers in your own mission?

Robert Santos: Thank you for that. Throughout history, art has been a central tool for societal living, for improvement in society, for getting people to care about things, for getting them to understand the importance of things like “Don't mess with Texas,” the good old ad campaign about anti-littering. That function of using creativity to apply to societal issues or problems, to promote a sense of belonging, to promote a sense of civic engagement-- we should go out and vote, we should not litter and those types of things are really advanced through art. I have witnessed firsthand-- and there are examples everywhere-- of how one can invoke artists and have them as central players in just about any endeavor so that they create pieces that blend together analytic types of things, data visualizations even, but in a way that is intrinsically both pleasing, offers different types of perspectives on what's going on in terms of the information and data that are being relayed back, and then reinforces the central message of either making sure you're a good citizen, or helping your neighbors, or participating in a census or a survey. We've seen things, say, in the 2020 decennial census even, where we had artistic reincarnations of things like the Loteria, -- there are cards that have little icons, very colorful, of different types of characters, and birds, and skeletons, and scorpions, and things of that sort. And because of the pandemic, we could not use our usual face-to-face methods, or community organizations couldn't do that. So rather than having a table in a grocery store saying, “Come fill out a census,” they were going out and distributing in community centers that were giving out water, and talking about best practices for vaccines and things. They were handing out these Loteria cards that, instead of the usual icons, they had different census characters on them, like an enumerator, or a little graph, or things of that sort. So it was reinforcing the necessity and the importance of civic participation, but doing it in an artistic way that was very pleasing to the eye, and got you to think, “Oh, this is really interesting.” There are many other aspects like that. I think it's so important that all federal agencies should have artists in residence. I would love to have that at the Census Bureau, and I'm thinking really hard about how maybe we can do that, because there are specific applications in just about everything we do that could benefit from the artist's touch. Their creativity, their interpretation of both the data, as well as the types of messaging we're trying to get out.

Maria Rosario Jackson: Well, the idea of artists in residence in every federal agency, that's music to my ears. Recently, we announced a collaboration with the Environmental Protection Agency around artists in residence at the EPA, focused on water. We're so excited about what is possible there and I think the inclusion of artists and people who are willing to use their imagination and help us get unstuck, I think, is so vital right now. As you were talking, Rob, about your experience with the Loteria cards during the pandemic, it made me think of a collaboration that the National Endowment for the Arts had with the Centers for Disease Control also during the pandemic. It was focused on working with community-focused, often arts organizations and artists, to help communities both process what was happening during the pandemic and also become vaccine-ready. So there was the deployment of artists' talents in helping people to understand complex health issues, in helping them to process their own feelings about fear and loss, and so much that we were going through in that period of time that was so disturbing and disruptive and full of unknowns. The collaboration that the Centers for Disease Control was able to foster with these art-based or arts-relevant, community-based organizations around the country, I think, made a really important impact in those places. The program was actually called Trusted Messengers, and it was looking to artists as people who could help explain things and who could help individuals and families and communities process something that was really difficult. I am so grateful that we had the opportunity to help to contribute to that kind of asset in communities around the country.

Robert Santos: Well, Maria, you need to know that in full disclosure, the notion of artists-in-residence came from the event I attended that you sponsored through NEA.

Maria Rosario Jackson: That's fantastic! We hope that that's a catalytic event. This is a summit that happened at the end of January, and it was called “Healing, Bridging, Thriving: Arts and Culture in Our Communities.” It was fantastic in that it demonstrated the importance of those intersections of arts and other federal agencies and other areas of practice. I'm glad that was inspiring to you, Rob. It was wonderful to see you there.

Robert Santos: It was great and, if you don't mind, I'd like to use this conversation and where we're going to illustrate how I used writing in the sense of art with healing. Because in 2021, I was the president of the American Statistical Association, the largest association of statisticians in the world and that was basically the time of the most intensive COVID infections. Society was pretty much still shut down and as one of the things that I had to do every month was a little newsletter and do a President's Corner. Typically it was, “Oh, there's this webinar coming up. You should maybe go check out some statistical methods.” I knew that the nation was suffering, and I knew that my fellow statisticians were suffering as well. So I used those 12 little blogs of a thousand words to instead send personal messages and reflections that would help folks understand that we're all in this together and that we need to help each other out and we can do so virtually. So I would tell stories about of resilience and how we need to tap into them and I told stories of creativity and mentoring and it was specifically focused on thinking as creatively as I could to help the folks that were suffering so much because they were stuck in their homes. So it was really a time of need and we need to think creatively and react creatively in those ways to try things differently and become vulnerable and just go out there to try to help people and help society.

Maria Rosario Jackson: Well, that's a really beautiful example and it makes me think about some of the words that the Surgeon General shared with us during that summit. I think it was really meaningful when he addressed the audience. I was in conversation with him and we were talking about the advisory on loneliness and social isolation and the need to address human connection as a health issue and, in the course of that conversation, he talked about how we should all see ourselves as healers and that healing didn't only happen in the context of the official medical profession, that through our creativity, our ability to connect as humans, and often through the things that we do through art, whether we're assembling to experience it together or whether we are in the creative process and making something, that these ways of connecting are, in fact, part of what we need as a nation to heal and that this was especially evident as a result of the pandemic and the isolation that people have experienced and, in some cases, continue to experience. Rob, your story made me think about that very recent call to action, I think from the Surgeon General, that we should understand the power of creativity in relation to our ability to contribute to healing.

Robert Santos: Well, I was honored to be able to sit and watch your dialogue with the Surgeon General and it was so inspiring, and I hope our listeners have an opportunity to hear that session and the entire summit if it was recorded.

Sunil Iyengar: Yes, it was. Actually, we have it on arts.gov, so we'll definitely make sure to get the word out. We would love more people to be able to experience that. Looking ahead, now that we've kind of had a really pretty expansive conversation covering a lot of ground, but at the same time really touching on some areas that I, for one, have not seen quite in this light before, I'm just wondering, in the future what kind of opportunities do you see for our agencies perhaps to think about working together? You mentioned the residencies idea, Rob. Are there any other things, Chair Jackson or Director Santos, you have in mind about how we might continue this really healthy alliance?

Robert Santos: Yes. What I've been doing at the Census Bureau are a couple of things that very easily can incorporate the arts. One of which is to stress the incredible value of a communication strategy to the public as part of our effort to serve the public as public servants who provide data and show the value proposition of our data as a method of engaging communities, of building trusted ecosystems, and creating a two-way partnership. As part of that communication strategy, there's nothing more empowering to me than to add artistic perspectives and build those in. So I see, moving forward, ways in just about everything we do, from creating data visualizations to creating online interactive tools that are visually driven, as well as things like webinars and audio podcasts like we're doing now, embed that artistic perspective in order to take something that might otherwise be rote and only of interest to a data nerd and transform it into a story to show the value of storytelling within the context of data and art. I think that can really empower and bolster the value of the information we're providing to the American public in a way that resonates with them, in different ways for different folks of different cultures, languages, perspectives, and so forth.

Maria Rosario Jackson: I think Director Santos has laid out some really interesting and compelling opportunities and I think there's so many points of intersection from continuing to push the envelope to figure out how we better account for artists, to continue to work with the SPPA as we do over the years to make sure it evolves in ways that continue to be relevant to our society, understanding the role that artists can play in making sure that people participate in the census and understand why it's important to do that. I think there's a role for artists in helping us to understand what the census tells us and augmenting that story, helping us to look at it from different perspectives and figure out what it means as we try to better know who we are as a country. I'm excited about what we might do together. I'm very excited based on this conversation and what I think we can dream up.

Robert Santos: We will get into good trouble together.

Maria Rosario Jackson: Yes, yes! What's funny is you have a Census director who can talk art and a chair of the NEA who can talk data. So that's a pretty cool combination.

Robert Santos: I think it is. You're offering different perspectives to the audience.

Maria Rosario Jackson: Yes, yes, yes.

Sunil Iyengar: Well, this has been a true pleasure and an honor, so thank you both for spending time today within this discussion. We look forward to working together more.

Robert Santos: Chair Jackson, thank you very much. It's been an honor to be on this podcast with you, and I look forward to working with you in the future.

Maria Rosario Jackson: Likewise, Director Santos. An honor and truly inspired about what we can do together.

Jo Reed: So, there you have it—an open and far-ranging discussion between the Chair of the National Endowment for the Arts Dr. Maria Rosario Jackson and the Director of the Census Bureau Robert Santos moderated by the Director of Research and Analysis at the Arts Endowment Sunil Iyengar in a special edition of Art Works. We’ll have links in our show notes to the Census Bureau and to “Healing, Bridging, Thriving: Arts and Culture in Our Communities,” the summit held at the Arts Endowment at the end of January. You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating on Apple, it helps other people who love the arts to find us. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed—and thanks for listening.

Jo Reed: Welcome to a Quick Study, the monthly podcast from the National Endowment for the Arts. This is where we'll share stats and stories to help us better understand the value of art in everyday life. Sunil Iyengar is the pilot of Quick Study, and he's the Director of Research and Analysis here at the Arts Endowment. Good morning, Sunil. And today, we have a special edition of Quick Study; Why don’t you tell us about it.

Sunil Iyengar: Yes, we have a 30-minute conversation between the Chair of the National Endowment for the Arts-that’s Dr. Maria Rosario Jackson, our fearless leader, and the Director of the Census Bureau Robert Santos discussing the profound connection between the arts and science.

Jo Reed: With you as the moderator! I know the NEA and the Census Bureau have a long history of working together in cultivating data sources such as surveys about arts participation, but how did this particular conversation come to be.

Sunil Iyengar: Well, I happened to be in a meeting, several months ago, with Chair Jackson and Director Rob Santos, and I was impressed with how fluid their conversation was—moving from the arts to science to back again, and touching on a variety of matters having to do with the role of artists as change-makers and also as stewards of trust in their communities. And I thought this would be a great podcast-- for others to hear first-hand how these two agency heads relate to each other—and how they see our missions are strikingly similar—especially since working across federal agencies and departments has been a key priority of Chair Jackson’s and then I thought, “Why not a podcast on Quick Study/” So I suggested it and they graciously agreed. And, the result is a far-ranging discussion that explores the intersection of arts, culture, and statistical science.

Jo Reed: I’m looking forward to it. Here is the conversation between Chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, Dr. Maria Rosario Jackson and the Director of the Census Bureau Robert Santos, moderated by Quick Study’s Sunil Iyengar who is the NEA’s director of research. Let’s listen

Sunil Iyengar: Director Santos. It's really a great pleasure to get to speak with you and Chair Jackson. I was wondering, for over four decades now, we at the NEA have worked closely with the Census Bureau to track levels of arts participation throughout the country and really have your agency to thank for that. We've used census data to report statistics about artists and cultural workers and arts organizations. I was wondering, Director Santos, if you can tell us from your perspective, why the arts merit that kind of attention from the federal government's largest statistical agency? In fact, why this whole endeavor of scientific measurement being brought to the arts from your perspective?

Robert Santos: Well, thank you very much for that question and it's an honor to be here today with Chair Jackson having this little chat. The tracking of public participation in the arts and active engagement as artists is incredibly important from a societal perspective and that's part of the reason that we make sure to do our best to collect good quality data from the American public on their participation in arts. We need to know who we are as a country and it's the mission of the Census Bureau to provide the highest quality data on our nation's people and our economy and, by knowing a little bit about how we participate in the arts, we can get a fuller breadth and appreciation for how we engage not only with the arts itself, but with each other as human beings in our society. That allows us and helps us with other research that shows that participation in arts and enjoyment of arts actually helps our health, our well-being. That is really highly valuable when it comes time to take a look at other socioeconomic characteristics, our health issues, either mental or physical limitations, employment, unemployment, our situations. Because art, when you put it into the mix of all the other types of services that we can provide, really completes the holistic picture that we need in order to understand us better and for government to better serve us.

Sunil Iyengar: I really appreciate that. And we're truly grateful for this partnership with the Census Bureau and with you, Director Santos, and the chair of the NEA, Dr. Maria Rosario Jackson, herself has experience, rich experience with research, with data, and using that for the purpose of community engagement and so I wanted to, Dr. Jackson, you may have your own comments on what was just said by Director Santos, but I also wanted to ask you if you could speak a little bit about kind of in your prior life as a researcher, educator, writer, and consultant, to what extent did data, or even maybe census data, help you catalyze conversation with funders, developers, and policymakers?

Maria Rosario Jackson: Thanks, Sunil. Like Director Santos, I feel so honored to be in this conversation and be in this conversation with Director Santos and in the position that he's holding now, which is so important. I want to riff on something, Rob, that you said that I think is so poignant, and that is we need to know who we are as a country. And the Census, as an agency, as a practice, is such an important element of that quest to understand who we are as a country and I think that we, from so many different perches within federal government and beyond, we can't do our best work if we don't know what we're dealing with, if we don't know the conditions that people find themselves in, if we don't know about the demographics of our society and I'm so grateful that part of what the Census has devoted attention and resources to is some sense of understanding cultural participation in the United States, because that, too, is part of understanding who we are as a country. I was very grateful for that phrase, Rob, and I'm sure we'll come back to it in the conversation.

Robert Santos: Thank you very much, Maria. I totally agree, of course, and I look forward to our continued chat right now.

Sunil Iyengar: Well, Robert, it's funny because when you were talking, and I think we can hear the passion that you have for the mission of the Census Bureau and how it intersects with what we do at the NEA, I felt that there's something maybe lurking beneath the surface there in terms of your own interests in the arts, personally, and I'd love to hear more about that. I know Chair Jackson often talks about living artful lives, so it'd be great to hear what a top statistical official of the government does with the arts in their own time.

Robert Santos: Yeah, it's really interesting that Maria talked about leading artful lives, because I think that artful lives are essential to being the full human beings that we are, the full contributors to society that we are and, in my case and the case of many other social scientists, an artful life, I believe, is an accelerator to being even better scientists. I often engage in my own personal art--photography. I was a live music photographer for South by Southwest festivals in Austin, Texas, for eight years. And that was the most incredible experience because you not only were able to practice the art of photography with some amazing human beings who are fellow artists and fellow creatives, but also we were able to witness the richness of the artists that were performing and the richness of the artists that were speaking about how they went about doing things like writing songs or coming up with a movie script or creating a new vision of what gaming should be in the technology arena. But when it comes to science, being artful is essential for being a better scientist, because science itself, the innovation and the advancement, doesn't necessarily come from a mathematical formula or a test in a lab. It comes from this creative spark. The creative spark is what propels the ideas to create a hypothesis, like theory of relativity or quantum mechanics, that type of thing and then go out and gather information and then verify or revise the hypothesis. You're getting knowledge gain. Knowledge gain, to me, and science is very much tied into creativity, which is fueled by living an artful life and that's what I found through my experience being a photographer and also being a writer. I can talk about that later on if you want, because I've taken enough time describing some of these other things.

Maria Rosario Jackson: I think it's such an important observation to recognize that there's a connection. I mean, oftentimes you think of it as those two areas of study, of practice, of funding, of policymaking-- you think of them as completely separate when they're not and recognition that creativity has to be a part of science and that there's relevance there feels really important. It makes me think about the efforts to move from STEM to STEAM. From science, technology, engineering, and math to having the arts included in that and that feels like such an important progression. Rob's comments just make me more excited that there is energy around this concept of STEAM and not seeing the arts as separate from our endeavors related to science and technology.

Robert Santos: Thank you for that, Maria. I actually would like to give an example of how some of those things tie together. When I was a live-music photographer, I would be engaged in taking photographs. There would be other photographers assigned to the event, and they would be moving all around to get all these different lighting and perspectives and so forth for their own vision and I found that I ended up doing the same thing and they would come to me and say, “Why did you insist on taking a photo of this person where there's just a black background?” and then I'd show them the picture and they'd say, “oh my God, what a different perspective. Here we are chasing light and you embraced the darkness.” So I offered a different perspective and that added value and insight into the work that they were doing. But, see, that lesson applies equally in science as well and especially in work that's done by the Census Bureau in terms of surveys and the cultural relevance and such. What we found is that there is no one best way to ask a question. You really need to take into consideration who is it that you're asking? When is it that you're asking? So that one can tailor and get different approaches to capture the most relevant and accurate information, and none of that can happen unless you get these diverse perspectives from different types of individuals. So that's actually how I'm working with the Census Bureau as a leader to show an appreciation for allowing different perspectives before any decision is made and that includes perspectives from the community because those are really, really cogent, informative perspectives that bring in cultural lenses and bring in different types of values and life experiences that we really need in order to do a better job and all of that ties up into art.

Maria Rosario Jackson: This idea of diverse perspectives is really getting my attention because it's so central to different aspects of my career and even what I'm doing at the Arts Endowment as chair now. But to offer an example from an earlier part of my career, when I was teaching, I often taught students from public policy, public administration, arts administration, a number of majors, let's say, that at their best are in the business of creating healthy communities where people can thrive as professionals. This is what they aspire to do. And I would often provide an assignment for my students that was about getting to know a community and, of course, the census information was invaluable because that began to paint the picture of the demographics of a community. And I would always supplement that kind of a resource with other perspectives and other ways of knowing. One particular resource that I would turn to when we were looking at communities in the L.A. area, there's a neighborhood called the Watts-Willowbrook neighborhood in Los Angeles and it's an area that is known for being challenging. There is a high rate of poverty. There is evidence of crime and there are a lot of characteristics that often are painted as community deficits. And it just so happened that there was an artist that helped to lead a planning process in that neighborhood and part of the planning process included conducting an asset map and one thinks, “Are there assets in a community that is so challenged?” And the answer was “Yes,” and those assets were often cultural, and the way that the artist did it was through engaging with community members to better understand the things that they were passionate about, the things that they loved, the things that they were involved in from a creative perspective. They created these really beautiful videos and even a book about the cultural assets in this neighborhood and so when we would look at that neighborhood in class, I would offer what was available from census data, what was available from administrative sources at different scales, whether it was state data or more locally generated data and then I would also layer in this cultural asset mapping that had been led by an artist in collaboration with communities in order to come up with a more comprehensive and, frankly, a more humane understanding of who lives here and what do they care about? What are their aspirations? It really was an effort to get students to think in a more holistic way about how you come to know a place and a people. And I go back to what you said earlier, Rob: We need to know who we are as a country, we need to know who we are as communities, in order to do our best work in creating places where people can thrive.

Robert Santos: Hear, hear.

Sunil Iyengar: That's a great segue because I actually was wondering in all this, as we talk about the arts and how they can complement science and improve social science and statistics gathering, what Maria is talking about is also the creativity and, also, to a large extent, trust building, right? It's artists and culture bearers as trusted, not only messengers, but helping to collect that kind of information and do it in a way that resonates with community members. Rob, when you were talking about really how essential it is to reach out into these communities and engage with them directly and how artists can help with that, do you have any thoughts about, from your perch at the Census Bureau, how can artists be part of this conversation and really help to communicate with the population in a way really provides information that's of use to the Census Bureau, but also is authentic to communities? Do you see a role for artists as trusted messengers in your own mission?

Robert Santos: Thank you for that. Throughout history, art has been a central tool for societal living, for improvement in society, for getting people to care about things, for getting them to understand the importance of things like “Don't mess with Texas,” the good old ad campaign about anti-littering. That function of using creativity to apply to societal issues or problems, to promote a sense of belonging, to promote a sense of civic engagement-- we should go out and vote, we should not litter and those types of things are really advanced through art. I have witnessed firsthand-- and there are examples everywhere-- of how one can invoke artists and have them as central players in just about any endeavor so that they create pieces that blend together analytic types of things, data visualizations even, but in a way that is intrinsically both pleasing, offers different types of perspectives on what's going on in terms of the information and data that are being relayed back, and then reinforces the central message of either making sure you're a good citizen, or helping your neighbors, or participating in a census or a survey. We've seen things, say, in the 2020 decennial census even, where we had artistic reincarnations of things like the Loteria, -- there are cards that have little icons, very colorful, of different types of characters, and birds, and skeletons, and scorpions, and things of that sort. And because of the pandemic, we could not use our usual face-to-face methods, or community organizations couldn't do that. So rather than having a table in a grocery store saying, “Come fill out a census,” they were going out and distributing in community centers that were giving out water, and talking about best practices for vaccines and things. They were handing out these Loteria cards that, instead of the usual icons, they had different census characters on them, like an enumerator, or a little graph, or things of that sort. So it was reinforcing the necessity and the importance of civic participation, but doing it in an artistic way that was very pleasing to the eye, and got you to think, “Oh, this is really interesting.” There are many other aspects like that. I think it's so important that all federal agencies should have artists in residence. I would love to have that at the Census Bureau, and I'm thinking really hard about how maybe we can do that, because there are specific applications in just about everything we do that could benefit from the artist's touch. Their creativity, their interpretation of both the data, as well as the types of messaging we're trying to get out.

Maria Rosario Jackson: Well, the idea of artists in residence in every federal agency, that's music to my ears. Recently, we announced a collaboration with the Environmental Protection Agency around artists in residence at the EPA, focused on water. We're so excited about what is possible there and I think the inclusion of artists and people who are willing to use their imagination and help us get unstuck, I think, is so vital right now. As you were talking, Rob, about your experience with the Loteria cards during the pandemic, it made me think of a collaboration that the National Endowment for the Arts had with the Centers for Disease Control also during the pandemic. It was focused on working with community-focused, often arts organizations and artists, to help communities both process what was happening during the pandemic and also become vaccine-ready. So there was the deployment of artists' talents in helping people to understand complex health issues, in helping them to process their own feelings about fear and loss, and so much that we were going through in that period of time that was so disturbing and disruptive and full of unknowns. The collaboration that the Centers for Disease Control was able to foster with these art-based or arts-relevant, community-based organizations around the country, I think, made a really important impact in those places. The program was actually called Trusted Messengers, and it was looking to artists as people who could help explain things and who could help individuals and families and communities process something that was really difficult. I am so grateful that we had the opportunity to help to contribute to that kind of asset in communities around the country.

Robert Santos: Well, Maria, you need to know that in full disclosure, the notion of artists-in-residence came from the event I attended that you sponsored through NEA.

Maria Rosario Jackson: That's fantastic! We hope that that's a catalytic event. This is a summit that happened at the end of January, and it was called “Healing, Bridging, Thriving: Arts and Culture in Our Communities.” It was fantastic in that it demonstrated the importance of those intersections of arts and other federal agencies and other areas of practice. I'm glad that was inspiring to you, Rob. It was wonderful to see you there.

Robert Santos: It was great and, if you don't mind, I'd like to use this conversation and where we're going to illustrate how I used writing in the sense of art with healing. Because in 2021, I was the president of the American Statistical Association, the largest association of statisticians in the world and that was basically the time of the most intensive COVID infections. Society was pretty much still shut down and as one of the things that I had to do every month was a little newsletter and do a President's Corner. Typically it was, “Oh, there's this webinar coming up. You should maybe go check out some statistical methods.” I knew that the nation was suffering, and I knew that my fellow statisticians were suffering as well. So I used those 12 little blogs of a thousand words to instead send personal messages and reflections that would help folks understand that we're all in this together and that we need to help each other out and we can do so virtually. So I would tell stories about of resilience and how we need to tap into them and I told stories of creativity and mentoring and it was specifically focused on thinking as creatively as I could to help the folks that were suffering so much because they were stuck in their homes. So it was really a time of need and we need to think creatively and react creatively in those ways to try things differently and become vulnerable and just go out there to try to help people and help society.

Maria Rosario Jackson: Well, that's a really beautiful example and it makes me think about some of the words that the Surgeon General shared with us during that summit. I think it was really meaningful when he addressed the audience. I was in conversation with him and we were talking about the advisory on loneliness and social isolation and the need to address human connection as a health issue and, in the course of that conversation, he talked about how we should all see ourselves as healers and that healing didn't only happen in the context of the official medical profession, that through our creativity, our ability to connect as humans, and often through the things that we do through art, whether we're assembling to experience it together or whether we are in the creative process and making something, that these ways of connecting are, in fact, part of what we need as a nation to heal and that this was especially evident as a result of the pandemic and the isolation that people have experienced and, in some cases, continue to experience. Rob, your story made me think about that very recent call to action, I think from the Surgeon General, that we should understand the power of creativity in relation to our ability to contribute to healing.

Robert Santos: Well, I was honored to be able to sit and watch your dialogue with the Surgeon General and it was so inspiring, and I hope our listeners have an opportunity to hear that session and the entire summit if it was recorded.

Sunil Iyengar: Yes, it was. Actually, we have it on arts.gov, so we'll definitely make sure to get the word out. We would love more people to be able to experience that. Looking ahead, now that we've kind of had a really pretty expansive conversation covering a lot of ground, but at the same time really touching on some areas that I, for one, have not seen quite in this light before, I'm just wondering, in the future what kind of opportunities do you see for our agencies perhaps to think about working together? You mentioned the residencies idea, Rob. Are there any other things, Chair Jackson or Director Santos, you have in mind about how we might continue this really healthy alliance?

Robert Santos: Yes. What I've been doing at the Census Bureau are a couple of things that very easily can incorporate the arts. One of which is to stress the incredible value of a communication strategy to the public as part of our effort to serve the public as public servants who provide data and show the value proposition of our data as a method of engaging communities, of building trusted ecosystems, and creating a two-way partnership. As part of that communication strategy, there's nothing more empowering to me than to add artistic perspectives and build those in. So I see, moving forward, ways in just about everything we do, from creating data visualizations to creating online interactive tools that are visually driven, as well as things like webinars and audio podcasts like we're doing now, embed that artistic perspective in order to take something that might otherwise be rote and only of interest to a data nerd and transform it into a story to show the value of storytelling within the context of data and art. I think that can really empower and bolster the value of the information we're providing to the American public in a way that resonates with them, in different ways for different folks of different cultures, languages, perspectives, and so forth.

Maria Rosario Jackson: I think Director Santos has laid out some really interesting and compelling opportunities and I think there's so many points of intersection from continuing to push the envelope to figure out how we better account for artists, to continue to work with the SPPA as we do over the years to make sure it evolves in ways that continue to be relevant to our society, understanding the role that artists can play in making sure that people participate in the census and understand why it's important to do that. I think there's a role for artists in helping us to understand what the census tells us and augmenting that story, helping us to look at it from different perspectives and figure out what it means as we try to better know who we are as a country. I'm excited about what we might do together. I'm very excited based on this conversation and what I think we can dream up.

Robert Santos: We will get into good trouble together.

Maria Rosario Jackson: Yes, yes! What's funny is you have a Census director who can talk art and a chair of the NEA who can talk data. So that's a pretty cool combination.

Robert Santos: I think it is. You're offering different perspectives to the audience.

Maria Rosario Jackson: Yes, yes, yes.

Sunil Iyengar: Well, this has been a true pleasure and an honor, so thank you both for spending time today within this discussion. We look forward to working together more.

Robert Santos: Chair Jackson, thank you very much. It's been an honor to be on this podcast with you, and I look forward to working with you in the future.

Maria Rosario Jackson: Likewise, Director Santos. An honor and truly inspired about what we can do together.

Jo Reed: That was a wonderful discussion between Chair Jackson and Director Santos! I thought you did a great job Sunil and I can see why you suggested this as a podcast! - I really enjoyed their ability to build on each other’s ideas—like a jazz riff!. I especially liked what Chair Jackson said at the end: “you have a Census director who can talk art and a chair of the NEA who can talk data. So that's a pretty cool combination.” She is so right!

Sunil Iyengar: Yes! I think we’re fortunate to have two agency heads who are so open to collaboration and who embrace “different ways of knowing,” to use Chair Jackson’s phrase. Here’s hoping there are many more, fruitful partnerships between arts and science agencies in the future! Also, Jo, I think our listeners will be interested to know that on April 2, the NEA will host a webinar featuring discussions with some of our other federal and non-federal partners, including Vipin Arora, director of the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The webinar will be about including data and evidence from the federal government in how we measure the arts through a new set of statistical indicators. People can go to arts. gov, and check out the “Forthcoming Events” page to learn more and to register.

Jo Reed: That’s a good place to leave it. Thank you Sunil. I’ll talk to you next month when we have our usual 5-10 minute podcast.

Sunil Iyengar: Looking forward to it.

Jo Reed: That was Sunil Iyengar. He's the Director of Research and Analysis here at the National Endowment for the Arts. You heard the discussion he moderated between the Chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, Dr. Maria Rosario Jackson and the Director of the Census Bureau Robert Santos You've been listening to a special edition of Quick Study. The music is We Are One from Scott Holmes Music. It's licensed through Creative Commons. Until next month, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

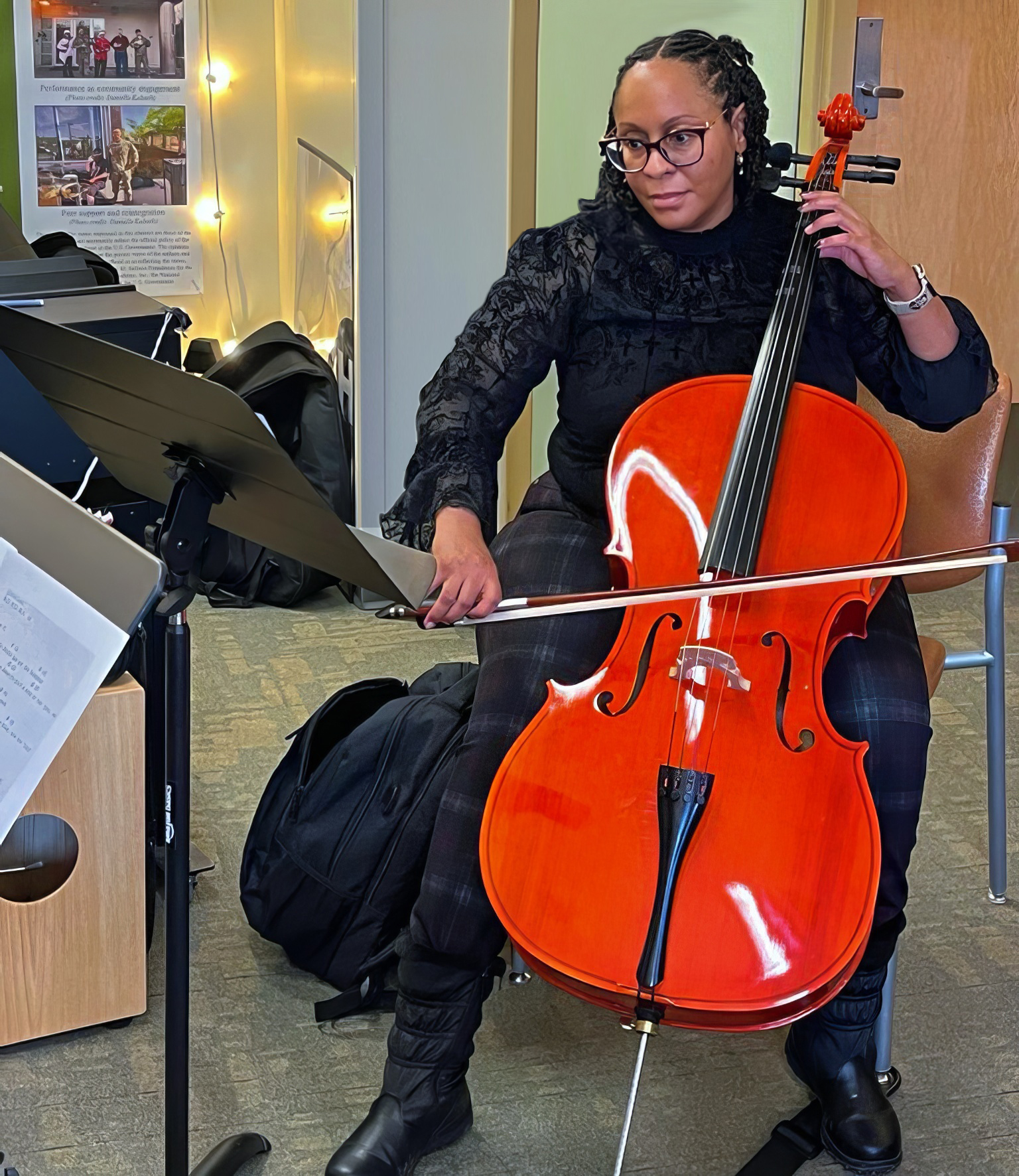

Juleaka M. Brown, SFC, U.S. Army (retired), playing the cello in the music therapy studio at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson. Photo by Danielle Kalseth

Music Credits:

“NY”, composed and performed by Kosta T, from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

“Soul Funk No.1” written by Amina Claudine Myers and performed by the Amina Claudine Myers Trio with Oluwu Ben Judah and Reggie Nicholson from the album, Augmented Variations.

"Dance from the East." Written by Amina Claudine Myers and performed by Amina Claudine Myers and Muhal Richard Abrams from the album Duets.

“Do You Wanna Be Saved” performed by Amina Claudine Myers and Generation 4 live at the 2019 BRIC JazzFest.

“African Blues” and “Steal Away” performed live in her home during my interview with Amina Claudine Myers.

Jo Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works, I’m Josephine Reed.

You’re listening to the music of pianist, organist, vocalist, composer, arranger, educator and 2024 NEA Jazz Master Amina Claudine Myers. Her contributions to jazz, gospel, and blues have not only crossed genres but have also bridged continents. Myers' journey through music has been a testament to her creativity, resilience, and profound influence on the genres she touches. From her early days in the church to her transformative years in Chicago with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) to her groundbreaking compositions and collaborations with musicians like Muhal Richard Abrams, Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt, Archie Shepp and Sola Liu, Amina Claudine Myers has shaped a path that's uniquely hers, marked by innovation and a deep reverence for the roots of American music. Her unique blend of jazz with gospel and blues sensibilities has resulted in a body of work that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. I was lucky enough to speak with Amina Claudine Myers shortly after she was named an NEA Jazz Master—Here’s our conversation

Jo Reed: Amina, first of all, congratulations on being named an NEA Jazz Master.

Amina Claudine Myers: Thank you.

Jo Reed: Many congratulations.

Amina Claudine Myers: Thank you. It's an honor.

Jo Reed: Tell me where you were born and raised.

Amina Claudine Myers: I was born in Blackwell, Arkansas. It's 50 miles northwest of Little Rock. I was raised partly in Blackwell, and I moved to Dallas, Texas, with my great-aunt who raised me, and then I moved back to Arkansas when I was 15.

Jo Reed: And your great-aunt and your great-uncle-- your uncle was a carpenter by trade, but he was also a musician, wasn't he?

Amina Claudine Myers: Yes. Uncle Buford, he loved music, and he started me on music. I never will forget. I used to march around the dining room as he counted, one, two, three, four. And I also sat in a little chair, a little child's chair, and he did the heel-toe thing, one, two, three, four, and that was the beginning of my music lessons.

Jo Reed: And when did you start studying music formally? You were very young, weren't you?

Amina Claudine Myers: I was about six years old, yes, and I went to the white Catholic school, which was about seven miles away. I still have my piano book from there. They were very nice, and I had piano lessons until I moved to Dallas.

Jo Reed: And did you continue studying in Dallas?

Amina Claudine Myers: Yes. Miss Fullilove was her name, and she'd sit on the side of the piano with a ruler. She didn't hit me or anything like that, but she was teaching me how to play hymns, and I didn't like that. Hymns were difficult for me at that time, but as I got older, I realized that was some of the best lessons I could have had, learning how to play hymns in those different keys, and then Dr. Mitchell came in. He was very good. He moved me quickly. In eighth grade, I was doing Chopin's Etudes. [gap in audio]

Jo Reed: Gospel music was a big part of your childhood, wasn’t it?

Amina Claudine Myers: Well, I had started playing gospel music when I was in Dallas. I started playing in church when I was about 11. Buying sheet music and stuff, that didn't appeal to me, because I played piano by ear, and people would always say "That girl can sure pick that piano." I didn't think about it. It was always someone giving me gigs. I didn't go looking, but I had nerve. I was studying classical piano. I would go to the Baptist churches. They had Easter plays, Christmas plays, and when they had a pianist he couldn't play. And so I started being the pianist for the vacation Bible school. In the meantime, the Baptist women in the church formed a gospel group. We were emulating the quartet singers, so some kind of way I became one of the pianists, the main pianist, and I also taught the songs. We were singing songs from the hymnal, like James Cleveland and other gospel writers, or Thomas Dorsey, who started gospel music. He used to play for Bessie Smith, but he turned into religious music. And there used to be-- when black people-- we were singing what they called sorrow songs or spirituals, but the gospel part was what caught on with young ladies at the Baptist, so I was doing gospel and then moved back to Arkansas. I rebelled about moving back, because I was in 10th grade, going into 11th grade, and I thought I was becoming popular in school. I didn't want to move back to Arkansas, back to the country. As I got older, I realized that was a wonderful life in the country. I rode my grandfather's horse without saddle, fruit on the trees, you know, plums, blackberries along the side of the road. The stars at night, it was beautiful. All of those things were what inspired me today, that country living. That was the best thing for me. Then I was able to go to college. I got small scholarships to go to Philander Smith College in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Jo Reed: When did jazz come into your life?

Amina Claudine Myers: I got into jazz when I got into college. The head of the music department had a band that went around and played the high schools, the black schools in Little Rock, and the band let me play. And I learned how to play the blues. So later on I moved out into the city. It was cheaper than living in the dormitory. In my second year, I moved out to the city. And this young lady came up to me. Her name was Gloria Salter from Detroit. She says "I have a gig for you, but it's playing in a nightclub." I said "Girl, I can't play in no nightclub." She said "Yes, you can. It pays $5 a night." So that's when I started jazz. So I went down to the Safari Room on Ninth Street in Little Rock, Arkansas. That was the street where all the activity, clubs, restaurants-- and I got the gig as a solo pianist. So that’s when I started jazz. I learned how to play jazz in the jazz club, play and sing. I learned how to sing "Stomping at the Savoy." That's Ella Fitzgerald's, 20 minutes long. I could sing it exactly the way she sang it. And there were musicians, piano players that came from Memphis, Tennessee, I would go visit them, and they'd show me the stuff, but just being around the jazz musicians. So the Safari Room I played solo. So second year the club owner put a bass player and a drummer with me. Then I was going to Louisville, Kentucky, in the summertime. I'd go there every summer, and the drummer lived in Lexington, Kentucky. He says "I got a gig for you, but it's playing the organ." "I can't play no organ." He said "Yes, you can. The pedals are like the keyboard." I knew three songs on the organ, "Money" <imitates melody>, I think "Summertime," but I learned three songs in a night. I put the words up on the organ, because I played by ear. And it was an organ gig. I was with a trio. Paid $15 a night, and I was able to save up money to help me in college, and I was still trying to play jazz and singing.

Jo Reed: And your degree at Philander Smith was in music education, correct?

Amina Claudine Myers: Yes. I needed something to be able to get work and everything, and so I got a degree in music education.

Jo Reed: And when you got your degree you ended up moving to Chicago.

Amina Claudine Myers: Yes. And when I got to Chicago I remember that I went down to the Board of Education, and they said they had nothing available. I was walking down the street feeling sorry for myself. I think I went to the Board of Education on a Friday, and on a Monday I get a call, said "Miss Myers, can you come in as a day-to-day sub?" Right down the street. I started teaching down there, and I would ask the principal "Should I come back tomorrow?" Finally she said "You keep coming back until I tell you not to come back."

Jo Reed: At that time, were you playing or going out to hear music?

Amina Claudine Myers: Yes. They had the black and white ball, you know, these events at the clubs. We didn't have no dates. There was one young man. He was a photographer. He asked me to go with him on the West Side of Chicago, because he was going to sit-in on the drums. So we went to the West Side, and he told the band leader that I played the piano. I said "Why'd you tell him that?" And then I had to play, and the band leader fired his musician and hired me, just like that.

Jo Reed: So you were teaching school and playing.

Amina Claudine Myers: On the weekends. And then I started playing for the church. I'd be over there asleep, and then I had to wake up and go up onstage I was so tired, and it only paid about $2 a Sunday <laughs> and 50 cent for rehearsal, so I was playing, <laughs> and I love choral music, playing jazz on the weekend, playing just church service. I was doing all of those things.

Jo Reed: Well, how did you come to join the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, AACM?

Amina Claudine Myers: Yes, that was another milestone in my life. Okay, I was playing with this band. Ajaramu, whose name was Gerald Donovan at that time, asked me to be in his group. He was a member of the AACM. I didn't know anything about the AACM. The AACM was developed by Steve McCall, the drummer; Phil Cohran; Muhal Richard Abrams; and Jodie Christian. They decided we should have some place where we can play, where we can rehearse and where we can write our music and have it performed. That was the purpose of the AACM, a place for musicians to create and play their own music, have a place to play. You had to be invited into the AACM. You can't go and join. I was selected, voted in to become a member. So when I got in, I had to write music and perform. I said "Wow." That was a challenge. I began to write, started writing for big band, and the AACM musicians would play the music, and that's how I learned how to write, and that made me more creative. All of them had their own style. They were a great inspiration to me. Improvisational music is very important in jazz. When I started playing with Ajaramu at the Hungry Eye in Chicago, I didn't know how to improvise. Ajaramu said "Listen to the horn players." I learned by doing. There was no such thing as buying no music. Played by ear. And I was fortunate to play with Eddie Harris, and Eddie played songs that he knew that I could play, because I was limited. I was playing with Eddie Harris. The club was empty, and there was a song that we played. Eddie usually played that in B-flat. Of course, I was on the organ. Well, this night he played it in the key of B, and he knew I fumbled. He told me "Learn how to play the blues in every key." He knew I was limited, and he was showing me what I needed to do without embarrassing me in front of people. I'll never forget that. The experiences of playing all this music, it was just beautiful. It was a beautiful time. [gap in audio]

Jo Reed: And you began playing with the great saxophonist and NEA Jazz Master Von Freeman

Amina Claudine Myers: Yes. I was fortunate enough to go and do a European tour with Von Freeman, the master musician in Chicago. For some reason, I was chosen to tour with Von Freeman. I had no idea what Von was going to play, but I was worried. I picked out several songs. I got over to Belgium, and I was worried, worried. I said "Von," in a nice voice, nonchalantly, "you have any idea what we're going to play?" He said "No, I do not," and that was it. <laughs> That was it. But after that, if I didn't know a song, after about one or two choruses I had it. Had a great time, because Von would play, and then he'd go back to the back of the stage and put his shades on, and Von would let us do what we wanted to do. He didn't announce no song. One song he announced was "Summertime," but no announcement. No, they'd just start playing.

Jo Reed: What about pianist and NEA Jazz Master Muhal Richard Abrams? I know you and Muhal performed together a lot, and you recorded some beautiful, beautiful music together, the album "Duet," for example. Tell me about that collaboration and how you and Muhal worked together.

Amina Claudine Myers: Well, Muhal asked me to do the duet. It was his music, but he let me do one of my songs, "Dance from the East." It's beautiful playing with Muhal, because, of course, you know, he's strong, and you've got to be able to be strong to make it even.

Jo Reed: In your composition, how would you describe the interplay between jazz and gospel and blues and the way that comes together in your own compositions?

Amina Claudine Myers: Well, I believe they come together because my experience is playing gospel. I love the blues. I love the hardcore blues. When I say "hardcore," you know, John Lee Hooker is one of my favorites. I like Jimmy Reed. So when I write music sometimes there are gospel songs I write. I consider them total gospel. And then when I write some blues, like "From a Woman's Point of View," I think of John Lee Hooker. It's the blues-blues. The choral experience in college-- I love choirs. You listen to choirs today. This gospel music is different from what I grew up in, because it has expanded and grown. They're doing wonderful work, but I'm doing the traditional gospel when I play. I first heard the quartets back in the '40s. The black quartets would travel to small towns. That music was so powerful, it drew everybody. And then I heard the country and western, Hank Williams, and the country and western music told stories that were very visible, so all of that is in the music that I write, but mostly gospel, jazz and blues.

Jo Reed: What precipitated your move from Chicago to New York

Amina Claudine Myers: I retired from teaching in 1969. They closed the music department, and we started having a lot of paperwork to do, and it seemed to be taking away from the activities with the students, but after I resigned I didn't have any money, so I went back to playing in the church. This is one of the big churches in Chicago. I think Mahalia Jackson had gone to this church. Very respected, conservative church. I was playing for weddings and funerals. The head of the music in the church was the senior choir that played the-- they sat in the back in the balcony with the pipe organ. Then they had the angelic choir, which sang short anthems. Then you had the gospel choir. I was a pianist for that. Then I became the organist for the young adult choir, and then members of the church wanted to take music lessons with me. And I was making a lot of money, but I felt like I was going backwards. I did all that, but Chicago was dying, as far as I could see, musically, because the AACM members were going to Europe and leaving. And I had come to New York several occasions, several times working with Gene Ammons. I started working with Gene Ammons around 1970 by going to see them in Kansas City.

Jo Reed: You played with him for two and a half years, didn't you?

Amina Claudine Myers: Yes.

Jo Reed: You came to New York in 1976. How was it sort of finding your feet and getting work and beginning to do gigs and play?

Amina Claudine Myers: Okay. I was walking in the Village, see if I saw a piano, somewhere I can go to try to get some work, and they said "Well, who is your agent?" I didn't know you had to have agents. And walking in trying to get work I met this man. I don't know. He owned a restaurant in Soho on Greene Street, and he hired me. He liked me, and it paid $40 a night. He had a little spinet piano, and it was a place where hockey members come, and he had a TV up behind the bar, and they didn't care nothing about the music. And I was glad to get the gig. I could play anything I wanted. It was a seafood place, wonderful food. Then the AACM, we were doing things at the lofts. Some of the AACM members, we performed in the loft scene. The loft scene was very popular here. I remember one night I got $6 and some change. So I got a few gigs. After the $40 gig, that's when I got hired for another restaurant, and it was a big, nice restaurant, and Jerome Harris was the bass player, and also Don Pate had been a bass player, and I had a singer and a young man. They would sing and dance to my music. Now, some of the jazz musicians didn't like playing there because the people came there to eat. It was a large-- it was a beautiful place. Upstairs they had like a cabaret, but I liked playing there because I could do whatever I wanted to do, and the people, sometimes they applaud, sometimes they wouldn't. Well, like I said, they came there to eat, but sometimes they'd be listening, but, as I said, that was a growth, because it was like a rehearsal. I liked that gig. I really did.

Jo Reed: Were you composing your own music at this time?

Amina Claudine Myers: A little bit, yes. I had the singers and dancer. They would sing songs that I had written. They were really good. That went on for a long time. And so Marion Brown, he came to me and said he wanted me to record his piano music, "Poems for Piano." So where I was staying there was a piano. The piano was out of tune, out of shape, but that's where I worked on his music, on that raggedy piano. And so we went to Yale. Marion would do his solo. I'd do his piano music. We went to Chicago, different places, and then I recorded "Poems for Piano."

Jo Reed: What year was that?

Amina Claudine Myers: It was around 1978, '79.

Jo Reed: Was that your first solo record?

Amina Claudine Myers: Yes.

Jo Reed: What was that experience like for you?

Amina Claudine Myers: Well, I was prepared to play his music. I just played it the best way I could. And then it was open for improvisation, and to me that improvisation is what opens up the music. When I was playing with Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt, it was traditional music, which is also beautiful, but by being in the AACM I started wanting to open up the music, instead of just playing, you know, repetition of playing, just open it up and expose it more, do more things when you open the music up.

Jo Reed: What are the opportunities but also the challenges of being a leader?

Amina Claudine Myers: Well, I became a leader. I don't know. I was put in those positions. I didn't realize that I was leading. I was just teaching the songs and stuff. There were church choirs that I led and directed. I went back to Arkansas and developed this group of young ladies that could sing all-- it was four of us, and I taught them the songs and everything. I was bold and daring. I see that now, but I didn't realize it at the time. I was teaching the grown people. I had several vocal students. This young man, he must've been in his eighties. He wanted to sing for the men's ceremony, men's day program. He wanted to sing the Lord's Prayer. I worked with him and worked with him. There was a part in the Lord's Prayer where he was singing incorrectly all the time. He couldn't change, but I encouraged him to do the song because this was going to make him happy, and that one little part that he sang wrong, that was okay, and he wanted to be able to sing. So I found out that I am a teacher, and I realized that. I've been one for a long time, especially with this music.

Jo Reed: Your voice is as distinct as your playing. How did you develop your vocal style?

Amina Claudine Myers: Well, the gospel music-- I could sing the classical music, you know, Handel's Messiah. I was a soloist in those. Like I said, Mozart's Requiem. But when I was singing rhythm and blues in Chicago, when I was singing jazz, I developed corns on my vocal cords because I was singing evidently on my throat, but when I sang classical music I was singing from my diaphragm. I don't know how that happened that I was singing on my throat and ruined my voice, but I had to learn how to sing from my diaphragm and get those notes and play in the keys that were comfortable for me, to, like I said, learn by doing and working.

Jo Reed: You also sing without words.

Amina Claudine Myers: Oh, yes. Songs without words started around 1980 when I recorded "African Blues" on "Amina Claudine Myers Salutes Bessie Smith." I was at the piano, and Cecil McBee was on bass, and Jimmy Lovelace was on drums, but Cecil and I were here working, and "African Blues"-- I just started. <imitates melody> That melody came up, then I was improvising. "Hey, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Well," you know, "Ahhh," and I stretched it out. I think it was about 15 minutes on the record. Cecil said the spirit came in the room when we did it on the record. We just did one take on that. And then I thought about being in Africa at a ritual where the spirit comes into you and you go with the spirit. The music takes the people into the trance. And, see, it's different every time. That's how those came about.

Jo Reed: Your composition "Improvisational Suite for Chorus, Pipe Organ and Percussion"-- first, what year did you write that? And what was the inspiration for that piece, and what was the whole process for creating it?

Amina Claudine Myers: I wanted to show opera singers in an improvisational setting because opera singers never improvise. And the classical singers, it's always the music. They're used to reading the music. I got a lyric coloratura, a lyric countertenor, and I got these wonderful singers and soloists just to show them improvising, and that's how that came about.

Jo Reed: In your own compositions, how do you see the interplay between improvisation and the structure that you create?

Amina Claudine Myers: In most cases, you play the melody, you sing the melody, and then you improvise according to what the song is about. And you're thinking you may want to show trees falling down. You try to make that sound. You want to put a slow, sad, sorrowful piece or a happy-sounding piece, then the piano is there for you to do anything that you want to do. And the organ. The kind of sound--you may want a dark, deep sound, and you just started creating things in your mind as you're playing to try to show what the song is about.

Jo Reed: You're so versatile.

Amina Claudine Myers: Oh, thank you.

Jo Reed: It's really quite extraordinary. As a soloist, with a sextet, with a quintet, with a chorus, on the organ, on the piano, you're singing. When you're about to begin a project, how do you decide where you're going to put that talent? How do you know "Okay, I'm going to write something for the organ. I'm going to write something for the piano. This is mainly for voice"? How do you come to that decision?