The Business of Books

Above, some of the new releases by Coffee House Press in spring 2010. Images courtesy of Coffee House Press

Approximately 40 years ago, a young writer named Allan Kornblum spent a life-changing afternoon in the Parish Hall at New York City’s St. Mark’s Church helping to hand-collate a mimeographed literary magazine. The technology has gotten more sophisticated since then but, as founder of Minneapolis-based Coffee House Press, Kornblum still spends his days hands-deep in literature. A former letterpress printer, Kornblum and his wife started the imprint in 1984 in Iowa; in 1985, they moved to Minnesota and became the first visiting-press-in-residence at the Minnesota Center for Book Arts. As Kornblum explained, “There were lovely aspects to letterpress printing, but there also were some serious limitations. And I wanted to be able to easily reprint a book if it was doing well. I wanted to be able to help authors reach a wider audience, and to publish fiction.” Today, from a former bottling house, Kornblum and his team of eight full-time employees annually publish 14–16 books, among them titles such as poet Patricia Smith’s Blood Dazzler, a National Book Award finalist, and Sam Savage’s Firmin, Adventures of a Metropolitan Low Life, an international bestseller.

According to Kornblum, approximately 3,000 manuscripts make their way to the press each year. More than half are from previous Coffee House authors, allowing for a handful of newcomers each season. Once accepted for publishing, it takes an average of two years—and as long as three—for a manuscript to appear on booksellers’ shelves. Kornblum estimates that the entire process averages about $20,000 in staff time per title.

For returning authors—as well as some local authors or ones who have been recommended by Coffee House associates—the manuscripts are vetted directly by Kornblum or associate publisher Chris Fischbach. A crew of carefully selected interns vets the rest. Kornblum said, “We ask them to pass books on to us if they either love them or hate them. Usually if they think they’re boring, they are.” He added that, although some manuscripts are reviewed by interns, the entire process is taken very seriously. “We are very respectful with the manuscripts that come in … even though some of them do seem to come from people who are not, shall we say, well-balanced.… We make sure that our interns know that there are to be no snippy responses or funny responses or irreverent responses to even the goofiest manuscript submission.”

Coffee House Press publisher Allan Kornblum prints letterpress broadsides in the press’s office. Photo by Esther Porter |

Accepted manuscripts go through a number of steps. There are two levels of editing: a substantive edit in which the content of the manuscript is scrutinized for any weaknesses with plot, structure, or—in the case of short fiction or poems—the order in which the individual pieces are presented. Later in the process, the manuscript is copyedited line by line. Meanwhile, marketing plans—such as scheduling galleys to be sent to reviewers and author book tours—are in development while book covers are designed, book jacket blurbs are sourced, and advertising copy is written. Even the distributor is already involved in the process; the staff has to let the company know details such as the page size, the thickness of the book, and the type of binding in order to establish mailing and other costs. The distributor also weighs in on the marketing plans, offering suggestions on the title, the cover, or the angle being used to promote the book. Along the way, as it goes through various edits, the book continues to make the rounds among the staff as well as back and forth to the author in the form of page proofs and galleys. “I think most people would be surprised by how much planning is involved and how much coordination is involved with the copy editor, the proofreader, the author, the designer, and our distributors,” said Kornblum. “There are a lot of people who get involved in reviewing each manuscript, checking it, and making sure that it fulfills the vision the author had for the book.… I think people would be surprised at how hard everyone in the publishing industry works.”

While Coffee House Press grew out of Allan Kornblum’s passion for antique technology, Narrative resulted from the digital revolution. Editor Carol Edgarian recounted, “When [Tom Jenks and I] started Narrative in 2003, nothing comparable was online offering first-rate content—not the New Yorker, not the Paris Review. But it seemed to us, perhaps because we live in California with Silicon Valley in our backyard, that the technological revolution was going to affect everyone and everything, publishing included. And that if writers didn’t get on board, and soon, they would be increasingly marginalized.”

From left: Joshua Clark, Tom Jenks, Rebecca Kaden, and Carol Edgarian at work in the Narrative office. Photo by Dana Tommasino |

With a staff of more than 100, including legions of dedicated volunteers, and an annual budget of approximately $500,000, Narrative publishes more than 350 artists each year. The magazine’s contributors include writers of fiction, poetry, and nonfiction, such as Amy Bloom, Chris Abani, and Gail Godwin. The table of contents also boasts cartoonists, graphic novelists, and journalists. Though the online model allows the magazine to publish more authors than many print houses, Edgarian maintains that the rigor of the editorial process is the same. “Once we accept a manuscript, we work one-on-one with the writer— editing, nurturing, nudging—to bring forth the best that piece is destined to be. From there the piece goes through rigorous copy-editing, on into production. Then, instead of binding, the manuscript gets put into various formats, which can include such platforms as audio, video, online, print-on-demand, Kindle, and very soon we’ll be launching an iPhone app.”

Although Coffee House and Narrative deliver their final products in different modes, in many ways the two presses are more alike than different. Echoing Kornblum’s sentiments, Edgarian is extremely proud of the attention with which the press reviews manuscripts. “Every manuscript submitted to Narrative, whether it comes through a prominent literary agent or from a rural outpost, receives careful consideration. Every manuscript that shows signs of promise receives a response: a note of encouragement, a request for more work, or an extensive collaboration through successive drafts until the piece is right. We do a lot of nurturing of new talent.”

Publishing—whether in print or online—is an expensive proposition. Kornblum explains that his press has three primary revenue streams. Income from the press’s distributor, which sells the imprint’s titles to bookstores, wholesalers, and other vendors, accounts for about 90 percent of sales earnings. In-house sales, which includes everything from titles sold directly through the Coffee House website to special orders such as to schools, accounts for the remaining ten percent. Finally, the press garners income from selling subsidiary rights—such as anthology, electronic, and translation rights—the profit from which is split 50/50 with the author. Overall, about 70 percent of the press’s budget comes from earned income, though Kornblum said there have been times when it has depended more on grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and other funders.

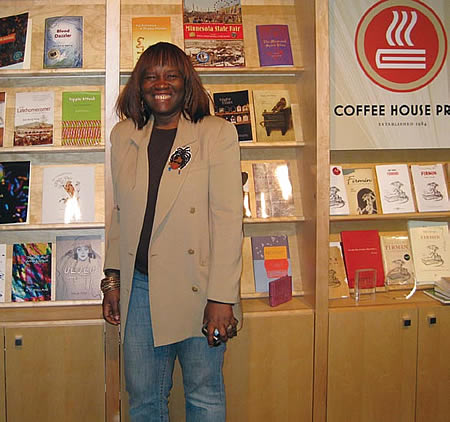

National Book Award finalist Patricia Smith at the Coffee House Press office. Photo by Esther Porter |

Funding is also a pressing concern for Narrative, particularly as its content is distributed free of charge. After a period of self-funding, the editors began to seek donor support. With the encouragement of those donors, the magazine subsequently looked at generating earned income. “The whole idea of the magazine— to give away premier new work for free, yet pay authors competitively—is pretty revolutionary. It’s a tall order. Through premium content, a nascent advertising program, merchandizing, and contest and entry fees, we’re working to narrow the gap between donated and earned revenue. Only very recently the balance is about equal. We still have a lot of work to do.”

Despite the countless challenges of independent literary publishing, Kornblum and Edgarian have no plans to slow down. And neither is overly concerned about persistent evidence that the literary audience is shrinking. In Kornblum’s estimation, keeping and growing an audience for literature is the publisher’s challenge. “I think that books need to get better. Publishers need to explore ways to continue to add value to the books they make. In some instances that might mean returning to some of the design values of the past, in which a book was designed to help enhance the vision of the author and to reflect the beauty and the import of what the author was trying to say.”

Narrative co-founders and editors Carol Edgarian and Tom Jenks with author Robert Stone at an event sponsored by the literary journal in 2009. Photo by Dana Tommasino |

Edgarian is equally hopeful that quality material will attract readers. “Give ’em the good stuff—I mean stories, poems, essay, graphic novels, literary puzzlers, letters to a young author—and they will come. I just have to believe that, and seeing that our readership has grown 50 percent yearly, I think that the stats prove it. The desire, the urgency even, to be told a great story— to be moved, entertained, incited, illuminated—it just never wanes….We are in an enormously inspiring and exciting time. Everything that looks like a challenge is also an opportunity.”