From the Ground Up

The free Twilight Concert Series, produced by the Salt Lake City Arts Council, lights up summer evenings in downtown Salt Lake City, Utah. Photo by Douglas Barnes Photography

For passengers lucky enough to catch certain Connecticut Transit buses on a Saturday or Sunday afternoon, a simple commute can transform into an unexpected artistic experience. Theater groups, spoken-word poets, bilingual storytellers, and even African drummers take passengers by surprise with intimate, on-board performances, delighting them as they wind through city streets.

Artists gone guerilla? Quite the opposite, in fact— such performances are part of the Exact Change program created by the Arts Council of Greater New Haven (ACGNH), which books artists on public buses throughout the area. “It’s our fourth year working with Connecticut Transit and we’re still evolving the project and learning,” said Cynthia Clair, executive director for the ACGNH. “Exact Change is great in that it brings art directly into the community—and it encourages people to use mass transit more.”

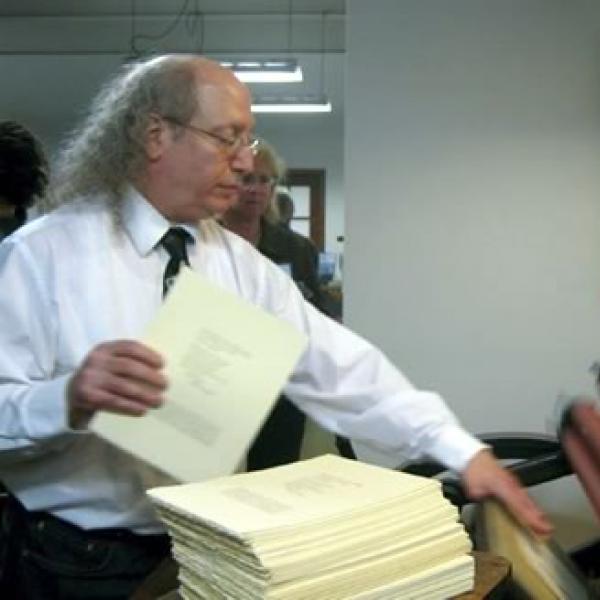

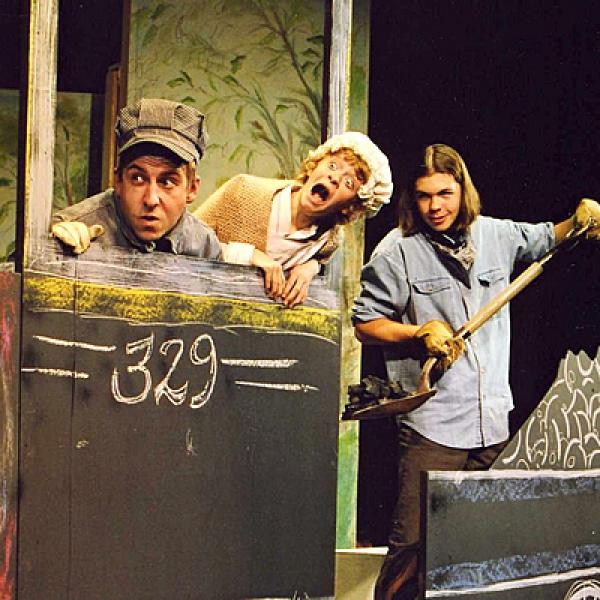

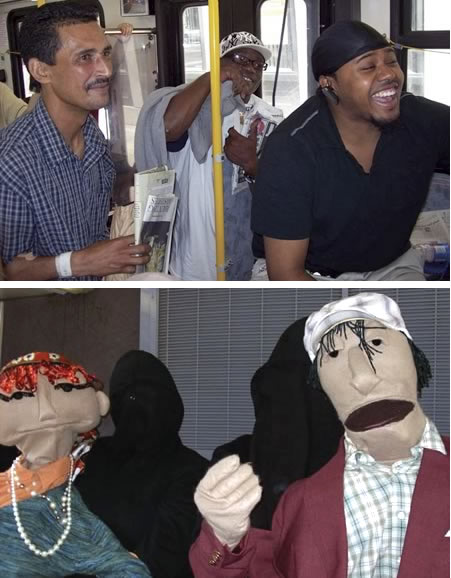

As part of the Exact Change program created by the Arts Council of Greater New Haven, riders traveling by bus from North Haven to the New Haven Green enjoyed a performance by members of the New Haven Theater Company during which actors manipulated bunraku-influenced puppets to tell stories of journeys and travel. Photos courtesy of the Arts Council of Greater New Haven |

Exact Change is just one of the community-focused programs executed by local arts agencies (LAAs), philanthropic organizations that respond directly to the arts participation needs of the neighborhoods around them. And while initiatives like Exact Change showcase the fun and creativity inherent in LAAs’ work, these agencies face a unique set of challenges. Between mandates to nurture highly diverse local scenes, adapt to ever-changing community needs, and find ways to fund it all amidst a down-turning economy, LAA leaders face considerable obstacles moving forward.

“Our mission is to connect artists with the public,” said Nancy Boskoff, director of the Salt Lake City Arts Council (SLCAC) in Utah. “Well, that’s the short version,” she added, laughing.

LAAs often support local arts efforts on a wide variety of fronts. Salt Lake City’s Living Traditions Festival, for example, an SLCAC program supported by the NEA, celebrates folk and ethnic artists through demonstrations, food, and music, drawing 50,000 visitors annually. On a different note, the SLCAC manages the city’s public art program, commissioning sculptures to adorn parks and train stations.

For Clair and the ACGNH, arts leadership begins with arts promotion. “We publish The Arts Paper ten times a year and give it out free at 200 locations around the community—coffee houses, venues, libraries. There’s a column called ‘The Artist Next Door,’ where we introduce readers to artists living and working in their midst.

An Asian youth group performing onstage at the Living Traditions Festival in Salt Lake City, Utah, produced by the Salt Lake City Arts Council with support from the NEA. Photo by Douglas Barnes Photography |

“Another area we focus on is support for arts organizations and artists. We do professional development workshops to help our constituents develop marketing and business skills, and we give a lot of one-on-one advice and technical assistance, since some organizations we deal with are very small and don’t have professional staffs. They look to us for guidance on many issues, and sometimes that’s just pointing them in the right direction for the help they need.”

For LAAs to address the evolving needs of their communities, Clair emphasized the need for open communication. “We interact with our constituents on a very regular basis, and even run into people on the street. So we’re constantly checking in with folks. New Haven is a small city, so it happens both formally and informally.”

With creative endeavors often running the gamut from folk dance and experimental theater to installation sculpture and fiction writing, providing an umbrella for an entire arts community can prove a daunting challenge. “We look to see if we’re touching all disciplines, either directly or indirectly,” said Boskoff of the SLCAC’s work. “We don’t do a film series, but we do support nonprofits that work in film through our grants program. So we always ask ourselves, are we filling a niche in Salt Lake City, or are we helping someone else fill that niche?”

An opening reception for a local artist’s exhibit in the Finch Lane Gallery of the Art Barn in Salt Lake City, Utah. Photo by Douglas Barnes Photography |

When it comes to staying relevant within a community, small efforts can yield big results. “In Salt Lake City, we now have lots of people who ride bikes, so at the Twilight Concert Series, which averages attendance of 15,000, a local bicycle collective provides valet bike parking. It adds to the feeling that everyone is part of the community.” For Clair and ACGNH’s Exact Change, a similar attention to detail—and sensitivity to the more micro needs of her communities— has been key. “Some bus routes have lots of kids, while some others go through neighborhoods with mostly Spanish speakers. We try to program our artists according to the demographics they’re serving.”

Whether they publish arts papers or sponsor performances, LAAs rely on external funding to do their work, and the methodology of money acquisition unfolds differently for each agency. “Many arts councils have support from local governments,” said Clair. “We receive state funding only. Otherwise, we are very reliant on membership dollars and private giving from individuals, foundations, and corporations.”

For the SLCAC, a slightly more complex model applies. “We are a municipal agency, so we get appropriations from the city, and we are all city employees,” said Boskoff. “But we also have a nonprofit associated with the agency, which makes it easier both to accept certain donations and to pay our artists very quickly—musicians, for example, on the same night they perform. It was a quirk of history that we have a combination of public and private, and it works for us.”

Given the current economic downturn, LAAs nationwide have been forced to re-evaluate the way they work. “To date, we’ve cut back services where it’s least visible to the public,” said Boskoff. “Quality is still very important to us. We have a gallery where we no longer have weekend hours, though we hope to reinstate them. We have a lunchtime concert series daily in the summer that we’ve reduced by a couple weeks. We don’t cut back on artist fees and our programs are still free to the public—we try to support our events on earned income like concessions, in addition to sponsorships and public funding.”

In New Haven, the ACGNH responded to the downturn by directly engaging the community. “We gathered folks in meetings to find out how the economy was affecting them,” said Clair. “There’s a growing realization that the nonprofit arts model, which has essentially been functioning the same way since the mid ’60s, is in need of tweaking—especially after the NEA arts participation study, which showed declining attendance at arts events in traditional arts venues. We can no longer really do business as usual, so we just launched a program with EmcArts out of New York that focuses on innovation. It offers organizations in our communities the chance to dig in deep and do challenging work around this notion of adaptation.”

Baba David Coleman entertains the audience at the annual Audubon Arts on the Edge celebration in New Haven, Connecticut, supported by the Arts Council of Greater New Haven. Photo by Harold Shapiro |

Though national and state agencies may claim greater economic firepower when it comes to helping U.S. artists, the relationship between LAA and community is a unique and valuable one. “We’re part of the community fabric that we’re serving,” said Clair. “We know the idiosyncrasies of our districts and we find that we’re helping not just our friends in the arts world, but the larger community as well.” Boskoff echoed the sentiment: “One of our hallmarks is that we present the artists’ work in a professional fashion, so the artists feel as good as the audiences do, and there’s a great satisfaction to knowing that our work makes a difference. Salt Lake City has a very lively, talented arts community, and we take great pride in working at the local level to promote that.”

Clair continued: “We’re not just something that is nice and fluffy and entertaining. What we do branches out into everything from working with economic development and youth education to looking at things like, ‘We’ve got empty storefronts. What can we do together about that?’ Not that LAAs have all the answers, but we can be part of the solutions.”