Early in the Morning 'til Late at Night

Mary Bischoff and fellow Eisenhower Dance Ensemble dancer Demetrius Tabron rehearse for the February 2010 performance of NewDANCEfest VIII. Photo by Lynne Ford

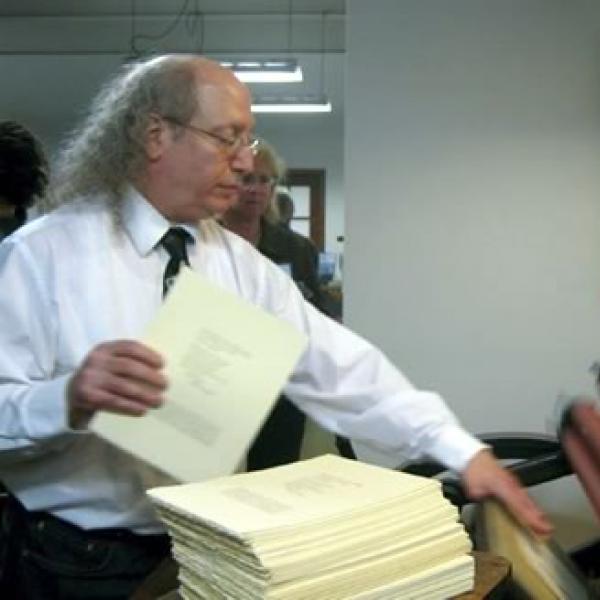

Like many others across the country, each morning Mary Bischoff wakes up between 6:30 and 6:45 am. Bischoff frets over what to wear to work, makes lunch, plays with her dog, and watches Good Morning America before heading out. But unlike many workers, at nine am Bischoff takes her place at a dance barre rather than behind a desk. As one of six members of the Eisenhower Dance Ensemble (EDE), based in Rochester Hills, Michigan, Bischoff takes class for an hour-and-a-half each morning, followed by a company rehearsal until 3. At three, she starts her second job as the assistant director for the EDE Center for Dance, which offers dance classes for children and adults. In her administrative role, Bischoff tackles a range of tasks, including program development, staff management, and long-range planning.

Three days a week, at five pm, Bischoff changes gears yet again. “I go in to teach,” she explained. “I teach mostly ballet, but I also direct a student company, which is mostly junior high kids. They learn pieces and they perform in the pre-shows for EDE.” Bischoff’s typical day ends around eight, when she’ll have a second dinner with her fiancé, having eaten her first dinner before teaching class. She confessed, however, that while she likes to spend her evening watching reality TV, she often is also online for at least another hour catching up on work e-mails and other tasks.

Bischoff wanted to be a dancer since grade school. “I never had a single doubt or question growing up as to what I wanted to do with my life. I wanted to dance. I didn’t know how I was going to do it or in what way I was going to do it, but I knew that it was going to be part of my life.”

Working with EDE is a dream come true. Bischoff joined the company as an apprentice dancer, after working with the ensemble during their residency while she was a student at Oakland University. “I just was amazed by the company. I thought the dancers were awesome. I put it in my head that that was the level I wanted to work toward.”

Bischoff keeps up her grueling pace almost year round. As an independent contractor, Bischoff doesn’t get paid for most of her vacation time, nor can she claim unemployment. It’s a predicament that’s not unusual for smaller dance companies. She noted, “We know about this ahead of time when we get in this company. We’re just advised to budget that money so that it will last.” Bischoff added that the company is currently working out how to hire ensemble dancers as employees to ease the dancers’ financial burden.

As an independent contractor, Bischoff also pays for her own health insurance, a monthly expense that costs nearly a week’s salary. “Some dancers choose to go without it. And that’s kind of a scary thing,” she acknowledged.

Mary Bischoff and her fellow EDE dancers bring Laurie Eisenhower’s work to life. Photo by Riina Ruben |

Even with three jobs, Bischoff grosses an average of only $30,000 each year. Approximately one-third of her earnings goes to job expenses. For a working dancer, this includes everything from gym memberships to stay in shape between gigs to dance apparel and shoes not covered by the company to travel money for teaching gigs to the multitude of muscle creams, foot tapes, heating pads, and other aids that dancers use to care for their bodies.

Bischoff acknowledged that her occupation requires lifestyle trade-offs. “When I got this job, the idea of earning a paycheck, I thought it was amazing. I still think it’s a great deal to get paid for something that I love to do. But I remember moving into my first apartment and thinking, ‘It will never get better than this.’ But now, being a little bit older, I bought a house almost two years ago, which is a lot more money than renting an apartment. Because I want to have a house…. I just have to work a little bit harder.”

Bischoff also struggles with the perception by others that, as an artist, she doesn’t really work. “We are a touring dance company and still, on the road, we’ll have people in our hotels or even at a performance that say, ‘So is this a hobby?’ It’s difficult to answer those questions patiently all the time. We all went to school, have degrees in dance, and work extremely [hard]…. [This is] what our passion is. But it’s also work because you don’t want to dance every single day of your life. Some days, you get there and you don’t like performing and rehearsal and dancing and using your body. It might be sore or tired or you just don’t feel like it, and you have to…. It’s too much work to just be a hobby.”

The cover of an issue of Beautiful/Decay, an art magazine produced by Amir H. Fallah. Image courtesy of Amir H. Fallah |

Two thousand miles away in Los Angeles, just as Bischoff is starting her first class of the day, visual artist Amir H. Fallah is getting back from his morning workout. Two days a week he is up at 5:30 am, checking e-mail and grabbing a quick breakfast before heading out for a run or to the gym. (On the days he skips the workout, Fallah lets himself sleep in till seven.) By eight, he is at his studio where he paints or works on other art projects until 10. He then heads down the hall to his “day job” as publisher of Beautiful/Decay, a triannual contemporary art magazine Fallah founded 16 years ago when he himself was just 16. As told by Fallah, the majority of his day at the magazine is spent “either on the phone or e-mailing or i-chatting. I’m usually just attached to my laptop.”

Fallah discovered the visual arts through skateboarding, which he picked up soon after immigrating with his parents to the United States from Iran. “I came here when I was six or seven. I got really into skateboarding, and I think skateboarding actually has lead to everything that I do now… I got into graffiti art through skateboarding, and in eighth grade I decided I wanted to take art classes so I could get better at graffiti. Once I started taking these art classes, I realized, ‘Wow. Art’s really kind of exciting.’” He earned an BFA from Baltimore’s Maryland Institute College of Art—with 80 percent of his tuition paid with scholar-ships—and an MFA from the University of California,Los Angeles.

According to Fallah, his determination and work ethic are an inheritance from his parents. He believes that he differs from his art world peers in that he is comfortable making money from his artwork. “My parents moved to America in 1987 with $82, and so I watched my dad work seven days a week for 15, 20 years straight. Now they live in the suburbs of Virginia, and they have their Lexus SUV. But they worked for all of that. So working hard and taking pride in your work was really instilled in me at an early age. You know, a lot of artists feel bad about making money, but I don’t resist making a profit. Everybody should make a living and live comfortably. And if you can do that doing something that you can stand behind and believe in, then, why not?”

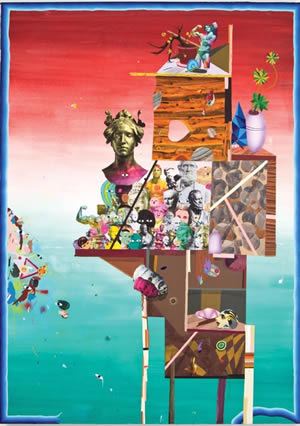

Flex Your Head (2008) by Amir H. Fallah. Image courtesy of the artist |

Approximately 50 percent of Fallah’s income is from Beautiful/Decay and from his partnership in Something in the Universe, a design company. Fallah acknowledged that he never expected to support himself as a businessman. “I never started [the magazine] as a business. It was just a project that kind of kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger…. I never meant to have employees or have to deal with payroll and sick days and all that comes from running a company. It was a lot of trial and error because I was just a stupid painter going to college. I wasn’t a businessman with a business plan thinking, ‘All right, this is how I’m going to make a living.’”

The balance of his income comes from sales of his artwork. Fallah is adamant that artists should be compensated not just for the materials cost of a particular piece but also for the time spent making the piece, just as workers in other sectors are paid for their time. “If you spend an entire month on a painting, if you had a decent job, let’s say for a month you make five or six thousand dollars. Well then, that painting has to be worth at least five or six thousand dollars because you spent an entire month. And that’s not including the time you sit around thinking about it because making art isn’t one of those things where you can just get up and go… It’s not as easy as it seems. If it was, everybody would be doing it.”

The Ultimate Mom Painting (2009) by Amir H. Fallah. Image courtesy of the artist |

Although the day-to-day details of their lives as working artists are very different, Fallah shares Bischoff’s sentiment that the emphasis in the phrase “working artist” should be on the word “working.”

“[Making art] is definitely work with a capital ‘W’… I get up and I punch in at my studio and I get down to business. I don’t have any days off from Beautiful/ Decay. Most artists, they teach and have two or three days a week where they’re just in their studio. I don’t have that luxury, so I get two hours every day to work, and I do it religiously. Most artists I know, I tell them that I wake up at the crack of dawn and paint. They’re like, ‘You’re nuts!’ But I have no choice. It’s either that or not make any artwork.”