The Art and Soul of the Community

Local artist Jim Gier was inspired by Orton's Art and Soul project to lead free outdoor painting sessions in Starksboro. Photo by Merlin Thompson

A bucolic town of nearly 2,000 people, Starksboro, Vermont, is home to eight working farms and a cohort of maple sugar producers. It's also home to several mobile home parks, and has only recently exceeded the population peak it saw back in 1860. Like many rural towns, Starksboro struggles with planning for future growth, while at the same time maintaining the pastoral characteristics that make it an attractive community in the first place.

According to the Orton Family Foundation, founded by Vermont Country Store chief Lyman Orton, the inimitable characteristics of communities like Starksboro are their "heart and soul assets." As Orton's Betsy Rosenbluth explained, these are "what really matters to people about where they live, both in terms of the place and in terms of their connection to each other." The foundation started its Heart and Soul initiative to help communities identify these defining aspects -- such as landscape, cultural heritage, and volunteerism -- which then serve as a basis for planning decisions, including zoning laws, development of public spaces, and even municipal signage.

Artist-in-residence Matthew Perry (center) with children from Starksboro’s Hillside Manor Mobile Home Park in front of Perry’s Art Bus, which he used to travel around the rural community. Photo by Caitlin Cusack |

The arts, in the form of storytelling, are a critical part of the Heart and Soul Community Planning process. Participating communities use activities such as story circles and intergenerational interviews to ferret out their shared values. According to Rosenbluth, "the point is that neighbors are listening to each other and that the community is listening to the stories as a whole."

Having seen success with the program, Orton expanded the role of the arts in a new project called Art and Soul. "We were interested in seeing whether [other art forms] could serve, in the way that storytelling did, as a different entry point for people to be involved in these discussions, in a way that could cut to what is the heart and soul because that is a much more emotional question than the right height of a building or the setback of a street," said Rosenbluth.

With a municipal planning process already underway and an elementary school nationally lauded for its arts education program, Starksboro was a perfect fit for the Art and Soul experiment. According to Robert Turner, Starksboro's elected auditor and longtime member of the conservation commission, the town had two main issues: geographic dispersal of the neighborhoods and the integration of its mobile home parks into the rest of the community. He added, "We don't have a central core village that a lot of New England villages have where you have the church and the school and the town store and those kinds of things. Instead we have these neighborhoods…and two of those neighborhoods are mobile home parks."

Residents of Brookside Mobile Home Park in Starksboro look at the signs created by the park's children during Matthew Perry's residency. Photo courtesy of Orton Family Foundation |

In the opening months of the year-long project, Orton engaged students from Middlebury College to conduct community interviews for the storytelling phase. The next step, however, was up to Starksboro: hire an artist in residence.

North Bennington visual artist Matthew Perry describes himself as a social and community artist. Perry said, "When I heard about the vision that Lyman Orton had about this project, it just resonated with me…because what he was saying was that he felt that artists should have a seat at the table in town government and school boards, and people in decision making should be listening to the artist's opinion because we approach problem-solving and challenges creatively."

Turner noted that Perry "really had the right personality and the right attitude, and that [attitude] was hands-on, let's get out into these communities, let's talk to these people, let's find creative ways to do things with these people that draw them out."

In fact, Perry's first priority was getting to know the townspeople. "I went around and [met] all of the groups, from firemen to the artists in town to the school to the teenagers. I went to the mobile home parks. I went to all of the different groups to find out who was in the town."

Perry had an unlikely ally in this quest: a converted school bus. "My art bus really played a big key part in this whole project, a lot more than I had thought.… It just brings the arts to the people because people don't really get out to art that much."

Rosenbluth agreed. "He was almost like the Pied Piper throughout Starksboro getting people excited about both doing art and just talking." Surprisingly, two words went unspoken during Perry's residency: "art" and "artist." "I teach a lot of classes and whenever I work with adult populations with art…they're kind of intimidated by it, and it freaks them out," he explained. "So I stopped [saying] that I'm an artist or that we're going to make art. I kept saying, 'Well, we're going to find some creative approaches to this.'"

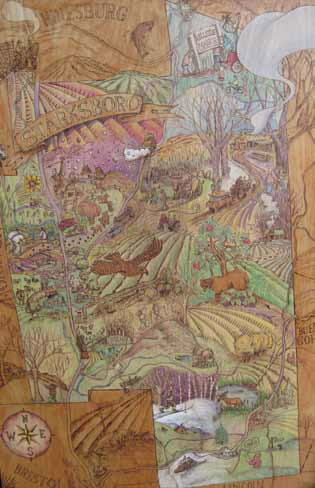

Matthew Perry's final artwork from his residency in Starksboro. Photo by Matthew Perry |

While there were many visual arts efforts -- new signage for the mobile home parks, a youth photography project, the painting of sap buckets for the annual sugaring festival -- Perry's signature activity was the "roadside conversation." Visiting each of Starksboro's enclaves, he invited residents for a neighborhood- wide potluck. Neighbors met each other, swapped stories, and were encouraged to reflect on what made Starksboro Starksboro. At each gathering a local artist was charged with making a piece of artwork in response to the conversation. One musician, for example, wrote a song inspired by "This Land is Your Land" about Big Hollow Road, a local thoroughfare. Perry claims an ulterior motive in recruiting the town's artists: "[I]t was important that the artists in the community carry on the work. Part of my job was to show them some different ways to work with people and particularly people in their own community."

Perry counts the roadside conversations as a major success of his residency. "Just the fact that we brought people together that hadn't talked to each other in a long time, people that didn't know each other…and everybody was just talking and having a great time… that alone was a key part of the goal."

Nearly two years later, Starskboro's Art and Soul project is still bearing fruit. For example, walkability emerged as a priority for the town's citizens. Turner reported, "We've built a small pathway that leads from the school to the main street and that is a visible, tangible example of how we've taken kids off the road and put them on a safer path to get from one destination to another. We've also moved the efforts to increase recreational trail access in our town's recreation fields, which happen to be a couple of miles distant from the village…. As part of Art and Soul, we're extending a trail to make it a longer loop trail, and we're creating a bridge so that the utility of this trail brings people out." The project includes funds for commissioned art works by local artists to be installed along the trail. Starksboro has also allocated additional funds for public spaces.

Ultimately, however, Turner believes the benefits of Art and Soul are more than civic improvements. "[W]hen you recognize that there's a lot of good in this community, and you're proud of the people, your neighbors, the volunteers, the people in the fire department, your elected officials, when you feel pride, I think that goes a long way toward increasing your social capital. And when the inevitable challenges come up that divide communities, I'm a great believer that this sort of capital banking will go a long way toward making those difficult challenges a lot easier."