The Art of Turning Things Around

The Batiste Cultural Arts Academy Marching Band participating in its first Bacchus parade during Mardi Gras 2013. Photo by James Wanamaker

Amid the legendary spectacle and fanfare of Mardi Gras, the Krewe of Bacchus parade is known as one of the more extravagant processions. There are 25 floats, three dozen escorts on horseback, and a celebrity king, whose royal duties have been performed by everyone from Will Ferrell to Hulk Hogan. This year, the marching band from Batiste Cultural Arts Academy had the honor of performing along the parade route. While it is by no means unusual for school bands to participate in Bacchus, it's something close to a miracle that this particular school found itself front and center, showing off its musical talent and fresh uniforms to the entire city of New Orleans.

A few years ago, Batiste Cultural Arts Academy—then known as Live Oak Elementary—was ranked as the lowest-performing school in Louisiana, which itself was ranked 49th out of all 50 states in terms of academic performance. Today, it is one of eight schools nationwide participating in Turnaround Arts, an initiative launched by the President's Committee on the Arts and the Humanities (PCAH) in 2012. The public-private partnership, which counts the NEA as one of its partners, is designed to help close the academic achievement gap with high quality and integrated arts education programs. In addition to professional training, leadership summits, and funding for arts specialists and supplies, each school is paired with a well-known artist such as Yo-Yo Ma, Kerry Washington, and Alfre Woodard, whose work with students have helped Turnaround Arts garner national attention.

The two-year program was developed in response to findings from Reinvesting in Arts Education: Winning America's Future through Creative Schools, a research report published by PCAH in 2011. The study drew on research that showed a strong correlation between in-school arts exposure and positive behaviors, including improved academic performance, increased attendance, and a higher probability that students will participate in extracurricular activities, attend college, and later gain employment. These positive effects were particularly pronounced in students from low-income, high-minority communities, who demonstrated the most relative academic improvement when given greater arts instruction. However, the report also found that these same populations were receiving the least amount of in-school arts instruction. In other words, "the kids in America who need the arts the most are getting it the least," said Kathy Fletcher, director of Turnaround Arts.

In the case of Batiste, which serves grades K-8, rampant turmoil destroyed any notion that school could be a safe haven or might offer a path out of poverty. There had been three principals in three years, less than 15 percent of students were reading at grade level, and according to teacher Glenda Poole, chaos reigned in the hallways. "[There were] children all over the place, teachers coming in at 8:30 and saying ‘I can't do this,' and at 8:45 they were out," she remembered. "It was just that bad."

In 2010, with the situation reaching crisis level, the school was taken over by Louisiana's Recovery School District. Batiste was awarded a School Improvement Grant from the U.S. Department of Education—a required component of the Turnaround Arts application—and the ReNEW Charter Management Organization was brought in. Working with the legendary Batiste jazz family, ReNEW changed the school's name, replaced most of its staff, and began to initiate a culture of accountability among both students and teachers. Although optional after-school arts programming was in place from the start, Ron Gubitz, principal for grades three to five, said that it wasn't enough to accomplish all that he envisioned.

"Our mission is to build a compassionate community of creative thinkers, leaders, and lifelong learners who are prepared for success in all future pursuits," he said. "If we're going to train our kids to just be somebody else's employee, that's fine. We can teach them the basics. But to teach them to be those creative thinkers and leaders, we have to teach them the arts."

Now, with funding and guidance from Turnaround Arts, Batiste is well on its way to becoming a true cultural arts academy. Art and music are "essentials," not electives, and are taught toward the end of every afternoon to encourage kids to stick around through the school day. Artists are brought in to teach theater or visual arts techniques to math, language arts, and science teachers, and a major donation of art supplies by Crayola "was the difference between being able to buy 100 on-level reading books for our lowest-level kids versus needing to buy art supplies," said Gubitz. Another $10,000 program grant from the National Association of Music Merchants has stocked Batiste with ukuleles, recorders, and drums.

"Maybe it's in my head, but I can see their brains changing as they try to figure out the chord fingerings," Gubitz said of the children learning to play ukulele. "It's actually teaching them multiple languages that they can bring back to the languages of reading, math, science, and social studies."

Poole, who teaches eighth-grade reading and provides coaching for other teachers, describes the recent change in culture as "huge." Since 2010, Batiste has achieved a 29-point increase in its state-issued school performance score, and 43 percent of students were reading at grade level by the end of the 2011 school year, with similar gains in math. Even more promising, 55 percent of students are currently on track to attend college, up from 21 percent. "Kids are doing much more, we're seeing more progress academically for them, and they're staying in school longer," said Poole. "We see the impact."

A thousand miles away in Southeast Washington, DC, a similar story is unfolding at Savoy Elementary School. In the year since Turnaround Arts has been in place at Savoy, "the whole world has changed," said Principal Patrick Pope. Pope is a veteran DC Public School (DCPS) principal who had previously developed an intensive arts curriculum at Washington's Hardy Middle School. When he arrived at Savoy in 2011, he began a similar plan at the consistently failing school, where only 20 percent of students tested as proficient in reading and 15 percent tested as proficient in math.

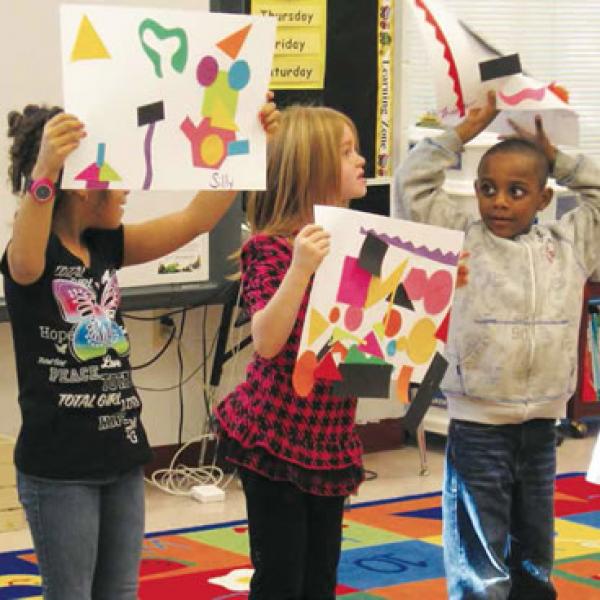

With the Turnaround Arts designation, Pope's plan has kicked into high gear. On a Thursday morning last April, one of three dedicated arts instructors guided children through the musical alphabet in the keyboard lab; students acted out a picture book in a classroom-turned-"Reader's Theater"; and another group performed their daily song and movement warm-up via Skype for Kerry Washington, the school's designated Turnaround artist. Nearly every inch of candy-colored wall space is plastered with student artwork, from collages inspired by Romare Bearden to reinterpretations of Jacob Lawrence.

But Pope is quick to point out that Savoy's art program "is not just a feel-good moment… We want the children to understand that we're using the arts as a vehicle for motivation." Throughout the school, there is an emphasis on order, purpose, and respect, a philosophy that affects everything from the way students walk down the hallway (single-file, hands behind their backs), to the way they interact with teachers (they're expected to listen, and they do).

"[We're committed] to making sure that [students] understand that the discipline and focus that they're going to learn is not just to carry a song or dance the Lindy Hop or create a beautiful masterpiece of visual art, but that those internal motivations and those internal self-regulatory aspects will play out in the rest of their lives," Pope said. "They'll play out in the math room, in their science lesson, and in their reading lesson."

So far, Pope's confidence seems well-founded. In the past two years, test scores have stopped falling, and teacher retention rate has remained steady. At a time when DCPS is shuttering 15 schools for low enrollment, Savoy's own enrollment is up by 18 percent. The school's suspension rate has fallen by 95 percent, and Pope said office referrals have also decreased dramatically.

While these are the type of evidentiary statistics that will likely prove critical to future arts education funding, there are other, unmeasurable effects that are just as important, if not more so. "There's a feeling of excitement and joy in these hallways," said Fletcher, of the eight Turnaround Arts schools. "A lot of our kids are facing post-traumatic stress because they live in high, high poverty. So to be able to go into school and have something that gives them a sense of happiness and confidence—that's what childhood should be about."

Even at Batiste, so recently a poster child of all that was wrong with the American education system, this sense of happiness has begun to spread. As Glenda Poole thought back to Mardi Gras, it was clear that participating in Bacchus was a major point of pride not just for students but for their teachers. "To see them come down the street…that was really huge for us," she said, smiling at the memory. "[All the teachers] got together waiting for them, and the kids were really excited to see us there. It was a wonderful thing, that's for sure."