From Pages to Museum Walls

Growing up in the 1960s and ‘70s, cartoonist Daniel Clowes kept his passion for comics under wraps, wary of earning a reputation -- especially among girls --as a "shut-in comics nerd." At that time, comics were the mass-market stuff of newsstands: they weren't cool, they weren't particularly innovative, and they certainly weren't considered to be art. But as alternative cartoonists such as Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman came onto the scene, comics began to find their footing as an artistic medium. In Clowes's lifetime, a passion that was once dismissed by art school teachers has now found its way onto museum walls. Case in point: Modern Cartoonist: The Art of Daniel Clowes recently opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA), marking the first major survey of the Chicago native's work.

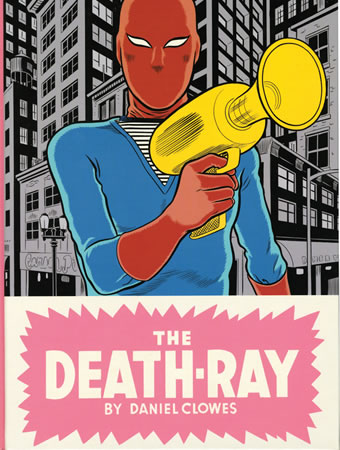

The show, which originated at the Oakland Museum of California, traces a celebrated career that has proven pivotal to comics' evolution. Known for his idiosyncratic characters and dystopian storylines, Clowes first gained recognition for his serialized comic book Eightball (1989-2004), which served as the original platform for his graphic novels Ghost World (1997), David Boring(2000), Ice Haven (2005), and The Death-Ray (2011). His screenplay for the film adaptation of Ghost World earned him an Oscar nomination in 2002, and turned the story's two alienated, angst-ridden teenage protagonists, Enid and Rebecca, into cult heroines. Original copies of these graphic novels, Clowes's drawings, and a number of his New Yorker covers will be on display at Modern Cartoonist, which will run through October 13, 2013. A few days before the show opened, we spoke with Clowes by phone about his career, how public perception of comics has changed through the years, and the pact he would have made with the devil.

NEA: What comics did you grow up reading?

DANIEL CLOWES: I was born in 1961, and I had a much older brother who was ten or 11 years older than me, and I inherited his huge stack of old comics from the ‘50s and early ‘60s. I had everything. He would buy anything that came out, so I had all the Superman comics that were popular in that era, all the science-fiction, the Archie Comics, Dennis the Menace -- everything. He was completely non-discriminating about what he bought. But the main thing I remember that really got me interested in comics was Mad magazine. He had all the early issues. I had this room that was like a paradise of comics.

We didn't have a TV when I was a kid, and I don't remember any children's books or anything. The only thing I had to do when I had to kill time was read the comics. I remember reading the comics before I could even actually read, trying to figure out the stories based on the pictures. So I feel, in some way, like it became a sort of second language to me. You watch very young kids trying to learn a language, and it comes to them very naturally when they're three, or four, or five. I think that was the language I was learning.

NEA: When did you first begin drawing?

CLOWES: Right away. I actually have a memory of drawing comics before I could read the lettering. So I drew the word balloons where they're talking, but I didn't know how to actually write. I just made chicken scratches, sort of fake letters in the word balloon. Which is very strange. I remember studying drawings of Superman, and his logo on his chest has that "s" in a shield. I remember not getting what that was. I thought it was a triangle filled with these weird little shapes. And then I remember one day, finally getting it was an ‘s.' I remember running downstairs to tell my mom, "That's an ‘s' on his chest!" I thought I was the first guy to figure that out.

NEA: I've read that when you realized you wanted to be a cartoonist as a teenager, you thought you'd probably end up inking for Marvel.

CLOWES: At best. If I could have, at that moment, made a pact with the devil, and [he said,] "You'll never do anything except ink for Marvel," I would have taken it.

NEA: When did you start realizing, or exploring, that maybe there was a world of comics beyond Marvel, beyond superheroes?

CLOWES: I knew there had been a world beyond. I knew about all these other kinds of comics that had existed in the history of comics. But at the time I was in high school, all there really were were the Marvel comics. It wasn't even a new thing; it was on its tenth generation at that point. I tried to have some enthusiasm for that stuff; it was just so bloodless and dull at that point. But then I started to become aware that there were these other things like National Lampoon magazine, [which] had funny comic strips in every issue. I started to learn about the underground comics, people like Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman. Somehow those didn't feel like they were officially part of the comics world until I got a little deeper into it. I felt like that was this rarefied world that nobody could ever enter, that had been sealed off. But after a while that became my main interest, to do those kinds of comics.

NEA: You've spoken about how even at art school, comics were not considered to be a viable art form. What was it like to be working in a medium that wasn't yet considered to have artistic value?

CLOWES: I always had this sense -- and I was very confident about this -- that I knew something that other people didn't. I knew that this form had great potential, and I knew that great things had been done that people were willfully ignoring in their dismissal of the entire medium. So I felt like I had it all to myself. Or, you know, me and the ten other people that were thinking of it this way. It was exciting to know that people who were regarded as experts, [like] my teachers and people in the art world, were wrong and I was right. I knew that as well as I knew anything.

NEA: Did you ever worry that the comic format might not hold up under the weight of some of the themes you've written about?

CLOWES: The only reason that it wouldn't is due to either my own limitations or to the fact that people have a hard time adjusting to the idea of a comic dealing with something other than guys punching each other or cats eating lasagna.

NEA: Now you have the Modern Cartoonists exhibition -- what has it been like for you to have your work exhibited in a museum?

CLOWES: It's one of those things that I just can't grasp. I can't wrap my mind around it. It has a very strange, kind of non-effect on me. It should be a much bigger deal. When I walked into the Oakland Museum for the first time, when all my work was on the wall, and [I] started looking at it, I didn't think of myself as the artist. I thought of myself as the art collector who had this great collection of this guy's work. I was really impressed with myself, like, "Wow, I have the best collection!"

NEA: Do you think that this exhibit, or exhibits like it, put pressure on the next generation of cartoonists? All of a sudden, there's the potential to produce museum-worthy work, which wasn't there before.

CLOWES: I guess I hope it does. Certainly nobody drawing comics should ever in a million years think about their end goal being on the wall of a museum. I certainly never once thought about that and never will. But I would hope that people would put a great effort into trying to do these comics the best they can, and to think of them as something that should be taken seriously, or at least given people's full attention.

NEA: How were comics perceived when you were growing up versus how they're perceived now?

CLOWES: I basically kept it a secret when I was in high school. I would have never in a million years told a girl in my high school that I had a really good collection of Fantastic Four comics or anything. Whereas nowadays, you can easily imagine somebody calling up a girl in their class and saying, "Let's go see the Daredevil movie." That would have never happened. I even remember when the early Superman movie came out with Chris Reeve, and only the nerdiest boys were interested, myself included. It was a totally different world. Although when I went to art school and started to meet friends who saw comics the same way I did, they were all really interesting artist-types. They were not your typical shut-in comics nerds.

NEA: Did you ever think that comics would become this kind of cool, hipster thing?

CLOWES: No. I can say no.

NEA: Was there a pivotal moment in the comic scene that you think not only changed the public's perception of what a comic could be, but critical perception?

CLOWES: I felt like there was, but I couldn't tell you what it was that made that happen. Part of it is, I think, there were people like me and the Hernandez brothers, and a small handful of us guys doing these non-superhero comics. And there were kids who grew up with that, that started seeing those in comic stores when they were 11 or 12, and got a sense of these other kinds of comics. Then those guys grew up and got jobs as art directors and journalists and things like that. So all of a sudden they were spreading the word about this stuff and I think that's, in a way, what happened.

NEA: Since you brought up the Superman movie, let's talk about your movie. What was it like to see Ghost World's characters living and breathing and talking on-screen?

CLOWES: It's as strange as you can imagine. It's sort of like having your thoughts projected onto a wall, in some way. It's like being able to literally, directly, transmit stuff in your brain into other people's brains. And yet, the way the movie looks is not exactly what I'm seeing in my brain when I'm writing the scripts or drawing the comics they're based on. So it's always a little strange. With the comics I feel like I'm transmitting, to the best of my ability, as exactly what's in my brain as possible. With the movies, it's through another filter of interpretation. So it's a very different thing.

NEA: Superman and Batman were obviously heroes for millions of little boys all around the world. But I feel like Ghost World's Enid is really a hero for struggling adolescent girls. Do you ever feel like your characters are heroes for the modern age? Is that something you strive to do?

CLOWES: Not at all. All I'm trying to do is create characters that seem like they're alive. To me, the primary goal in all my books is that you can close the book and feel like that person is still existing somewhere outside the parameters of the story they were just in. It's very heartening that people still respond to Enid and Rebecca, because they're from a totally different world that kids exist in nowadays. [Enid and Rebecca] don't have cell phones, they're not on Facebook, there's not a computer in the whole thing. They're reading the want ads in the newspaper. They have dial telephones. They're supposed to be intentionally anachronistic a little bit, that's kind of their thing. But still, Enid in this world would be texting all the time. Which is a shame, because that's a really boring thing to draw.

NEA: You mentioned that when you're drawing, you're trying to create characters that have their own reality; they're alive. What is that like to take the complexities of life, of thoughts, of feelings, and distill them into this limited number of words and panels?

CLOWES: Of course you have all these things you think you can do. You could write, for each panel, an entire page of prose, as you would in a novel. But then nobody would read it. There's something about comics that when your brain is looking at the pictures, there's only a certain amount of text you'll read. So yes, you do have to really pare it down. That's sort of the art of it, to figure out how to tell the story in a way that people can't not read it. That's the kind of comics I like to read myself, ones that I might not even be interested in. But all of a sudden I'm hooked into it, and I just can't stop reading -- there's something so compelling about it. That's what we're striving for. You don't always achieve it, of course.

NEA: Comics originated as a mass media form of entertainment, and then there came the alternative movement, which itself has become somewhat mainstream. Where do you see the future of comics going?

CLOWES: I have no idea. It's one of those things that the more I think about it, the more depressed I get, so I try not to think about it. But I think there will always be a place for books, for people doing these beautiful objects. But I suspect more and more of the general meat-and-potatoes kind of comics will just be on iPads and things. I find that a shame, because I like the physicality of these things. I don't keep track of anything I read on the Internet; it just sort of disappears. I like to have a physical record of everything I've read. It's nice to look across the room [at my bookshelves] and see this mosaic of all the things that have shaped my thinking.