Pure Expression

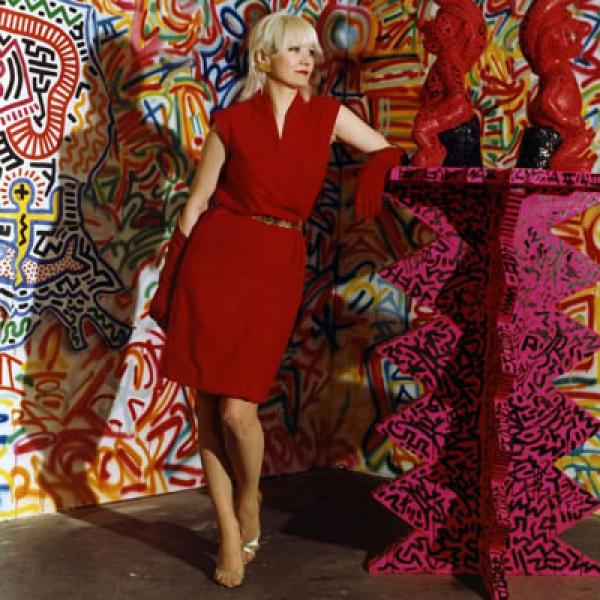

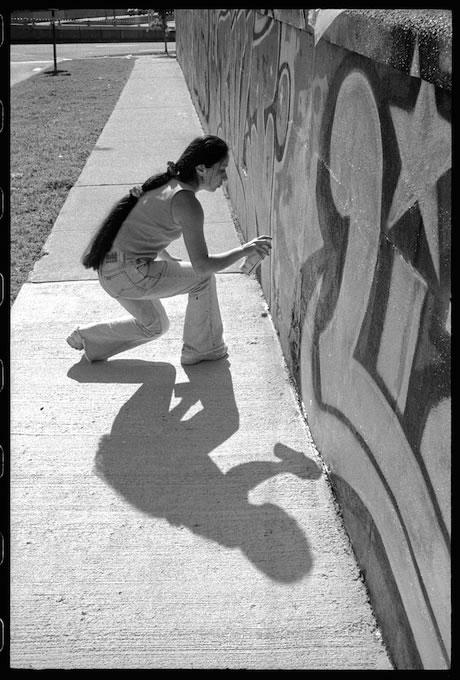

When Lady Pink discovered graffiti in 1979, her first canvases were New York City subway cars. Although certainly vandalism, some considered it art as well. Her work quickly evolved from tags of an old love's name, and at the age of 16, she was included in the landmark 1980 show Graffiti Art Success for America at the gallery Fashion MODA -- an exhibit which is now credited with helping graffiti transition into the world of fine art. One of the only women to run with The Cool Five (TC5) and The Public Animals (TPA) graffiti crews, Lady Pink is today considered to be one of the most accomplished female graffiti artists of all time.

Although her days of graffiti are long behind her, she continues to create murals and studio work, and has pieces in the collections of the Whitney Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands. She also shares her decades of experience by teaching young artists through mural workshops and university lectures. Here, Lady Pink discusses graffiti's early days, and what it has been like to witness the continued acceptance and blossoming of street art.

The Movement

When I first started graffiti I was only 15 and there was already a long history of folktales in the subculture. There were heroes and villains and great epic deeds. By the mid-1970s some of the guys had already achieved whole trains -- those are ten whole cars -- top to bottom, painting the entire train… and we all had to try to achieve the greatness that was already shown. Very quickly it got good. The tourists thought that the subway trains came like that. They thought it was quite charming -- they loved it.

[Street art] is a broad term for all the vandalism, but we specifically went for the trains. We didn't do street tagging. We didn't write on people's buildings. Our generation of graffiti writers, of the early 80s, specifically went for the subway trains.

Seeing your work rolling by on a massive train, roaring and making noise and dirty and gigantic and it's rolling with all that energy -- there is no other thrill and rush and excitement that you get by seeing your name roll by knowing that you were naughty and you got away with it.

But it quickly got out of hand. It was the ‘70s. New York City was in chaos economically and physically. Crime was rampant. By the early ‘80s, the city started to pick itself up and recover, and by the mid-‘80s, the graffiti had already been destroyed off the subway trains. They erased the graffiti with an acid, but it also destroyed the trains themselves, so they had to combat it in a different way. They developed the vandal squad, the graffiti police… [Graffiti] is very elaborate and stylized lettering -- you have to study it and be schooled in order to read it. The police not only learned how to run the train tracks, but they learned how to read the stuff and they learned who's who. By 1989 the subway trains were completely clean, and they wiped the graffiti off the face of the Earth.

There [also] were infamous people underground that would destroy others' work. They couldn't do any artwork themselves. So if they destroyed something nice, everyone was talking about them… It was internal strife. It was no longer just fun and games and playing cops and robbers. Folks dropped out left and right. People grow up, got to earn a living. The shelf-life of a graffiti writer is only about two to five years, before you grow up and you have to join the real grown-up life by getting a job.

Graffiti as Folk Art

We need rebellion in our society. We need someone to question the status quo. Otherwise, our society will be stagnant. Our country is based on rebellion. If not, we'd still be speaking in a nice British accent. The free thinkers, our forefathers, were the ones that set us free, and we still need it in our society.

What we have been saying for the last quarter of a century is that the art world has become elitist… That you have to study in college in order to be authenticated as an artist and for your work to be valid is nonsense. We are all capable of doing art and creating art. You don't necessarily have to go to art school to be an artist. You can be an outside artist. You can be a folk artist. That's what we are -- technically we are folk art.

If you are to define what folk art is, it's a grassroots movement. The young people who started the graffiti movement were teenagers, literally 13-, 15-, 16-year-olds making stuff up as they went along. The other street artists were also making stuff up -- the beginning street artists like Keith Haring and [Jean-Michel] Basquiat and Jenny Holzer and John Specter and Richard Hamilton. All of these cats were the very first street artists. They were working in different mediums…stencils and posters and bucket paint, brush paint. Certainly not with letters or subway trains and spray paint the way we did. They were the first street artists.

Teaching the Next Generation

The way I like to say it is I was discovered, [but] I don't stress that for young people I work with. I push them for scholarships and university. That's my goal. Only very few of us are discovered and maybe fell into it and made a career out of it. Most everybody else has to bust their butt in college.

I won't cross the line and do a wall or a spot that is not legal, that is not commissioned. I work with teenagers, so I try to set a good example…I see no need to do anything illegal.

We're teaching kids how to do art, how to copyright their work, how to document their work and how to present their portfolios and book gigs and write invoices -- all of those tedious things that go on above ground when you're a legal artist. There's a lot to learn and I teach a lot of young people that. I don't teach anyone how to be a vandal or a graffiti artist. That you're not going to learn from me.

On Going "Mainstream"

There has always been a backlash from the graffiti purists who feel that it belongs only underground, belongs only on the trains, [that] the minute you take money for your artwork, you're selling out. That kind of view did not affect me… It's difficult enough to be an artist, so when you're given an opportunity to put your foot in the door and to be noticed and support yourself as an artist, by all means go for it.

[The fear of selling out] is just a deluded, misguided loyalty to some underground nothing. Nobody has loyalty to that. It's idealistic and foolish. Sure, you can work sweeping floors and pushing paper, but if you have the skills and talent to be an artist, go for it. There have always been the haters and the jealous people that try to hold you back and call you a sell-out.

Doing graffiti taught us a lot of things like college would teach a lot of young people. That was our beginnings. We learned a lot. It gave us backbone. It gave us courage. It gave us confidence. It gave us all these gifts that you get to learn in college; we also picked [them] up. It builds character so that you can stand up for yourself in broad daylight and stand by your work no matter what the criticism. That takes a different kind of courage. Some people just do not have that. They would prefer to be anonymous and that gives them the bravery. They can't face an audience. They don't want to be celebrities. That takes a different kind of courage to be a celebrity and to stand by your work.

It's a huge responsibility to be part of such legitimate and awesome museums like [the Met and Whitney and the Brooklyn Museum]. But I've been training all my life for this, beginning since the age of 16. Even at the New Museum, in PS1 at 17, in solo shows at the age of 21. This is my career. This is what I do. I take it very seriously.

Street Art Today

Early on, rock-and-roll was outlawed and feared and all of that, banished from society and the people who did it were outcasts. Now we see where rock-and-roll has gone. There's punk rock, metal, pop, and even hip-hop. There are many different levels of it but it's still all rock-and-roll. And I believe that's where graffiti has gone. It's being labeled in general as street art, but the street artists work in so many different mediums that have nothing to do with one another.

Today, street artists are working outside of spray paint, with knitting, wood, rubber bands, pencils and stickers and bucket paint -- they're working with every medium possible…. For so long we have been given these urban landscapes that are dull and boring and utilitarian and gray. And then the street artists come along and we add some life and color and some urban love to our surroundings.

They're creating art for art's sake and not for profit. It's the purest form of expression you can imagine.