A Place for New Ideas

When it first emerged on the scene, punk was dismissed as the cacophonous ranting of angst-ridden youth. But what "the establishment" saw as adolescent rebellion went on to become a major artistic and cultural force whose influence is still being felt.

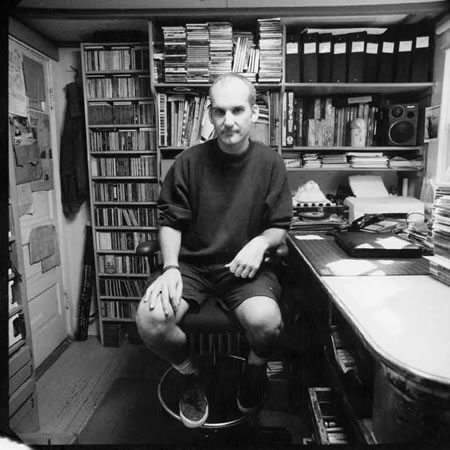

Ian MacKaye's place in punk music started in 1979 in his hometown of Washington, DC, when he began the Teen Idles with some high school friends. The band broke up in 1980, and pooled its money to create a recording of their band. In order to do this, they formed their own label, Dischord Records, which still exists today as an outlet for DC's independent music scene. MacKaye's next major band was Minor Threat, an influential band in the punk scene despite its short lifespan (breaking up in 1983). MacKaye's longest-running band, Fugazi, formed in 1987 and set itself apart from other post-punk bands with its dynamic rhythm section overlaid by jagged guitar playing and impassioned singing. Although the band has not broken up, they have been on indefinite hiatus since 2003. MacKaye's music took yet another innovative turn in 2005, when he teamed with Amy Farina to create the Evens, where he plays baritone guitar while Farina plays drums and both handle vocal duties.

MacKaye has been a steadfast supporter of the music community, ensuring that admission prices are kept low and only playing all-ages shows (which has meant finding new venues beyond the bars and clubs where most bands play). We talked with MacKaye by phone and below are his thoughts about becoming enamored with music, the punk scene when he started, and where punk is now.

From Woodstock to Punk

I always was really into music, and as a kid my parents had a record player. I would just listen over and over again to certain records. One that comes to mind is this guy Floyd Cramer, and I think he had a song called "Last Date." I just was hooked. He's a piano guy. And then by 1970 it was the Rolling Stones and the Beatles and Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. I really just loved these bands.

And at some point…Woodstock came out. I was so into Woodstock. And really, to this day, I still think about that movie. Alvin Lee from Ten Years After died recently, and I realized Alvin Lee's performance at Woodstock is so incredible. When he died, it made me think about how powerful an effect that had on me, that footage. It's a curious thing about documentation on that level. That one performance was so incredible. I have, in years since, come across other footage from around that era of [Ten Years After] doing other songs where I realized just how incredible and visionary he was as a guitar player.

And also the Who, because they broke their guitars and stuff. I was absolutely electrified by that. I remember actually getting toy guitars just to break them and then just wanting to play guitar so I could break a guitar, and then trying to learn how to play guitar, which was impossible for me. I couldn't figure it out. I played piano, but I was incapable of transposing from the way you played a piano to a guitar. I couldn't understand the way the notes worked on a guitar, because I had taught myself how to play piano.

So I gave up on the idea of being in a band. It seemed out of reach. It seemed to me that rock music was a pantheon. The people who were playing rock music were sort of in an elevated status and one that I could never reach or get anywhere near. So I gave up on the idea entirely and just became a skateboarder and listened to a lot of Aerosmith and Ted Nugent and that sort of stuff, anything heavy and hard, stuff like Parliament Funkadelic.

In 1978, I was going to Wilson High School [in Washington, DC]. At parties they'd start playing new wave stuff. You'd hear some Ramones song or a lot ofRocky Horror Picture Show -- that kind of stuff. These songs just started popping up. And they were aesthetically challenging for me because they weren't like hard rock.

At some point I actually listened to it. I studied it. I borrowed some records and I listened to it, and it was really earthshaking for me, because it was not only a music form that was terrifying and electrifying and all that, but it also was, I thought, within reach. It didn't feel removed. It felt like a secret language or a code that could be shared among a certain tribe, and that tribe was a countercultural tribe, and that's what I had been looking for in my life.

So for me the punk scene or the new wave scene or whatever it was called at the time, this underground, it was this idea of challenging conventional thinking, since conventional thinking is what got this culture into such a mess in the first place.

Starting a Band

[My band] Teen Idles, we largely played to our friends, and they liked us because they were our friends, and we had a good time. We were never careerists. It wasn't until maybe 15 years ago or something, or maybe ten years ago even, where some authority figure asked me what I did for a living, and I wrote down "musician." It had never occurred to me. I never thought about being a musician. I just was a kid who wanted to be in a band, which is different than being a musician. It wasn't a career move. I still don't think about a career. I just don't think like that.

All we were trying to do was create music so we'd have something to do, and other people would come make shows with us so they'd have something to do too. And we were making shows and we were forming a family, a tribe, and that was deeply important for kids, especially kids in Washington, DC, who are so marginalized for so many reasons.

I don't think teenagers in DC are taken very seriously. One thing about this town is that the economic canopy is government, so the arts are not taken seriously. So, for instance, if I say, "I'm a musician," a lot of people say, "Yeah, but what do you do for a living?" Very normal to hear that. But if I'm in LA or New York or Chicago and you say you're an artist or a musician, they're like, "Oh, that's great," because in those cities there is actually an arts or music canopy.

I think, in a way, part of the reason that the DC music scene was so thick, why we were so tight, is that if you live here for a while you start to recognize the tidal nature of the town, how many people come and go. Obviously you have the federal government, you have people coming and going [with elections]. But then you also have all of these students who are coming and going, and then there are huge rafts of people who come to make their bones. They come and work in DC for a while, and then they go back to where they came from. So when you live in that kind of environment where it's constantly people coming and going, like where water's just coming and going, you just hang on tight to something that doesn't move. And sometimes that has to be each other. I think we desperately wanted to feel a sense of rootedness, and we wanted to have a sense of something that was ours and maybe a culture.

The Creation of an Independent Label

[When the Teen Idles broke up], we had some money and we had a demo tape. Instead of splitting up the money and just making cassette copies, we decided that we would document something that was important to us. So we did, and the [Dischord Records] label was started in 1980.

Fugazi's first record didn't come out until eight years later -- unlike a lot of other bands, we had an infrastructure in place. The interest from major labels really didn't kick in until Nirvana hit in 1991…Nirvana had done that record Bleach, their first record, on Sub Pop, and they had sold maybe 40,000 copies of that record at the time when they signed to Geffen…By 1991 we sold hundreds of thousands of records, so we were way bigger than Nirvana at that time. You can imagine when Nirvana exploded the labels were like, "Oh, let's sign Fugazi."

Essentially we were contacted by virtually every major label in varying degrees, but it was never a consideration. It was never as if they had made an offer which we turned down. We never had lunch with them. Because we had a label, we had decided as a band that no amount of money for us was going to be worth the loss of the control. We wanted the control, which we still have. So, in theory, we turned down millions of dollars. I would actually posit that had we signed to a major label, we would've broken up because the structure is something we would not have been able to deal with as a band. We were very, very tight friends and still are very close friends, and it's a relationship, and that relationship was really founded in the environment that we ourselves created. Brendan [Canty] and Guy [Picciotto] and I had known each other since 1981 or ‘82. Joe [Lally] had been a friend since 1984 or ‘85. And we lived together and we were very, very close. The scene, our environment, is one that we built.

Defining Punk

If you ask me now what punk is, I would say it's the free space. It's a spot where new ideas can be presented without the requirement of profit, which is what largely steers most sorts of creative offerings in our culture. Some of the most brilliant people I ever met in my life gravitated around the underground.

Punk for me is a place that people gathered because they wanted to see new ideas, so that meant there was a lot of distasteful (perhaps) or unpleasant (perhaps) or just plain bad [ideas], but it's okay. It's like we were there for the offering -- but also in that you find moments of pure brilliance and genius.

The media has always been derisive about [punk] -- they've always said it was nihilistic or self-destructive, and there may well have been elements in punk that were self-destructive, they may have been nihilistic or moronic. But what I think is more important to think about is that even with those elements it was a form important enough to people to stick around. All these bands like the Minutemen, for instance -- who were such an amazing band -- traveled in the same circles as all these people who were so screwed up.

So those of us who are "construction workers" put up with all the craziness. We felt like, "Yeah, we want to make something," and that sometimes requires being in challenging company on occasion. But one of the great ironies, of course, is that the media's criticism of punk was also largely, in my opinion, what created those elements. None of my friends were morons who wanted to hit themselves with hammers, but that's the sort of kind of image that was being broadcast. I think the straight world was just freaked out. At any rate, this organic musical community or scene really exploded in America far below the radar of the industry. It was, I think, a true artistic blossoming. It was the real thing, and it had an effect that I think is still ringing to this day in our culture. Hence the fact that the NEA apparently wants to talk to me about it. I can assure you that if this was 1982 and I was in Minor Threat, the NEA was not going to be calling me.

The Legacy of Punk

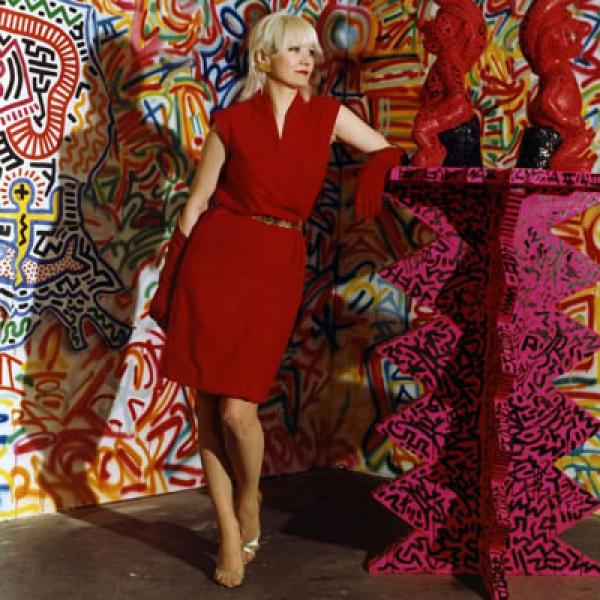

I guess the fact that there are these shows [the Corcoran Gallery of Art's Pump Me Up: D.C. Subculture of the 1980s exhibition and the Metropolitan Museum of Art's exhibition Punk: Chaos to Couture], and there is this sort of dichotomy [between the two exhibitions], is the legacy of punk. Punk forced the question, and it continues to do so. When I see the free space about punk, it's the same free space that once was occupied by folk or jazz or rock-and-roll or blues or beat or hip-hop. It's all the same thing. It was revolutionary. And I think the one thing about punk that kind of maybe made it more sustainable in a weird way or unusual way was that it was harder to co-opt it. [With] rock-and-roll, it was easy, but when you get down to the bones of punk -- it kicks back.

Occasionally our music will pop up in a weird place. It'll just pop up and quite often without our permission. So, for instance, there was a period of time where the [Washington] Redskins were playing a Fugazi song during their football games regularly. And in moments like that -- or when, say, in movies or television shows where the name or the music appears -- I can tell you for certain that there is no publicity agent involved. There's no machinery involved. I know that there's nobody promoting it. We own the publishing, so there are no publishers trying to get things into movies. Nobody's trying to exploit this work. I know that. So the fact that these things appear on the surface of mainstream, they bubble up to the surface, from my point of view it proves that the corporations haven't managed to erect their fence across everything. There are still paths where real art can make it, because people give a damn about real art.