Cosmic Creativity

When Dan Goods was studying graphic design, he figured he’d probably end up at an ad agency or some sort of commercial corporation. But these days, his artistic concerns are bigger than choosing the appropriate typeface, layout, and color. Much bigger. Like Jupiter-sized big.

For the past ten years, Goods has worked as a visual strategist at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. His job is to translate the technical, data-driven language of JPL’s missions into engaging, public-friendly works of art. When negotiating his position, the original idea was that Goods would create visualizations communicating JPL’s work. But Goods pushed back: he didn’t want people simply to see the universe; he wanted them to feel it.

“What is great about being here is that I get to work with content that is, in its essence, mind-blowing. But you still have to express it in a way that’s mind-blowing as well,” said Goods, who was named “one of the most interesting people in Los Angeles” by LA Weekly in 2012. “I want to be able to give people a moment of awe about the universe that we live in.”

Take his piece Beneath the Surface, inspired by the Juno spacecraft’s mission to Jupiter. Launched in 2011, Juno will penetrate Jupiter’s thick cloud cover for the first time, allowing scientists to study the planet’s evolution and properties, including the depth of its powerful lightning storms. Intrigued by the idea of these massive storms, Goods used vaporized tap water, ultrasonic misters, infrared lights, and audio of thunder to simulate what it might be like when Juno descends upon the gas giant.

He filled a darkened room with a vast, amorphous cloud, backlit by an eerie reddish glow. In a nod to the instruments needed to see below Jupiter’s clouds, the installation’s “lightning” was created using infrared lights, which are invisible to the naked eye but can be seen with a cell phone camera. As thunder crashed all around, people were able to use their phones to embark on their own exploratory mission of the lightning storm.

“That experience of going into this room, seeing this crazy cloud, touching it, using their cell phone—it’s all an experience I like to hope people take with them for a long time,” Goods said.

Although Goods said he has always been fascinated by space, he didn’t consider pursuing science professionally until he arrived at the Art Center College of Design, also in Pasadena. When nearby California Institute of Technology opened its summer research program to Art Center students for the first time, Goods became one of the first three artists accepted. He found himself working alongside conceptual artist David Kremers to help create the “Mouse Atlas,” a digital tool that visually mapped the development of mice. While a far cry from astrophysics, it left a profound impression on Goods.

“The experience of hanging out with scientists was fascinating for me,” he said. “I loved the big ideas that science works with, and I felt like I was doing something meaningful.”

The experience was so positive that after graduation, Goods focused his job search within the world of science. After a number of false starts, he was invited on a tour of JPL with the president of Art Center and the director of the NASA facility. “I had about two seconds to sell myself,” Goods remembered. Eventually, he was able to show JPL’s top brass the Mouse Atlas and a traveling pipe organ he had invented by rigging soda bottles to a car. The projects were innovative enough to convince JPL staff that he had more to offer than the animations they had in mind.

“Most of the time, if someone says, ‘Do you want to do animations?’ You say, ‘Yes,’ when you need a job. You don’t usually say, ‘Hey look at this bottle project,’ to a person from NASA, expecting them to be enticed by it. But I took the risk, and it paid off,” said Goods. He was told he’d get six months and then they’d re-evaluate. That was ten years ago.

|

It didn’t take long for Goods to make his mark. One of his earliest projects, The Hidden Light, illustrated the difficulty of locating planets, which are often obscured by the blazing light of much larger, brighter nearby stars. “They have an analogy [that] if there is a firefly in front of a spotlight in New York, you’re trying to see it from Los Angeles,” he said. “That gives you a sense of the difficulty and challenge.” Goods’ own challenge was how to turn this idea into a compelling experience for the public. The result was brilliant in its simplicity. He trained two light sources onto a blank, outdoor wall: a movie projector and a 20,000-watt spotlight. Because the spotlight was so much brighter than the projector, the projected film could only be seen when people stood in front of the spotlight, blocking its luminosity. As people experimented with the different ways their shadows could reveal the image on the wall, the installation became a throng of walking, dancing, playing, and perhaps inevitably, shadow puppeting.

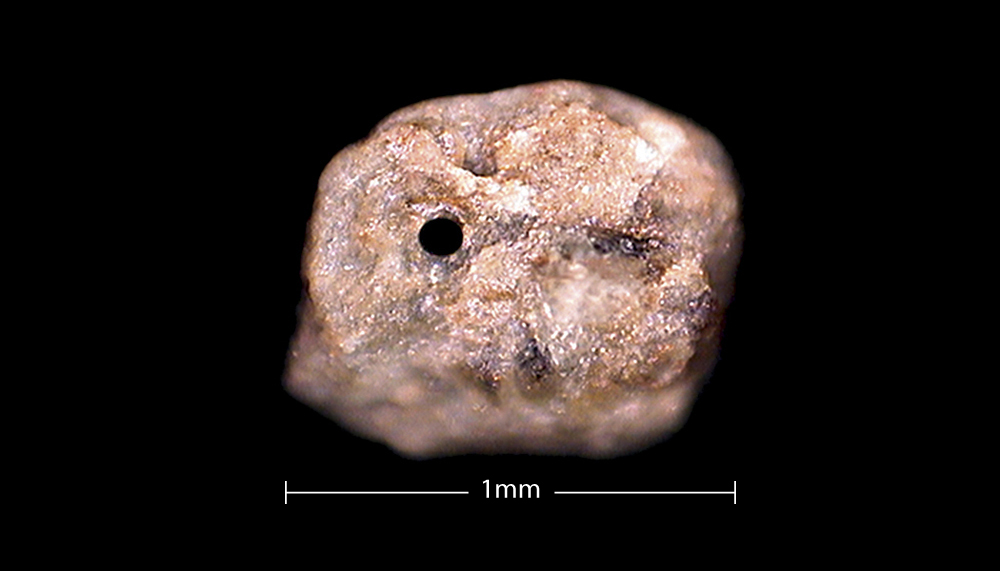

His other projects for JPL have all shared Goods’ signature originality and sense of wonder. For The Big Playground, Goods drilled a hole in a grain of sand and displayed it under a magnifying glass in order to depict the relatively tiny number of planets discovered in the Milky Way. Six rooms were then filled with sand to represent the galaxies still awaiting human discovery. Another installation, For Those Who Dream, Far Away Does Not Exist, was inspired by the cosmic aspirations of NASA employees. Set within a darkened room, the piece projected shifting colored lights onto blocks of aerogel, a nearly weightless material used on twin Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity. The stunning interaction between this space-age substance and light resulted in an ethereal installation that was a dreamscape all its own.

|

Despite the endless inspiration space may provide, Goods has come to serve as something of a muse himself. In recent years, he and his team—which now includes people from the worlds of architecture, advertising, film, special effects, and product design—have expanded their role, and are beginning to help design actual missions. While a mission’s technical details are still left to the experts, Goods and his crew are there to spur the out-of-the-box thinking so necessary for the study of space.

“When scientists and engineers come to our studio, they’re in a mindset that they want to be in a creative space,” said Goods. “They feel permission to be more creative because we’re around.” When it comes to mission design especially, “We’re trying to figure out how our role can enhance the thinking and creative process they have.”

In turn, his own creative process has come to resemble something akin to the scientific method. After meeting with scientists and engineers to determine “what is meaningful and powerful and interesting about a topic or a person,” he asks questions, conducts research, experiments, fails, then experiments again. “Hopefully,” he said, “you succeed at some point.”

And succeed he has. Throughout his career of melding art and science, he has managed to continuously capitalize on a central component the two fields share: their ability to make people step back, open their eyes, and see the world (or in this case, the universe) in ways they never have before. Goods however had a different way of putting it: “I’m hoping I can create things that make people go, ‘Wow.’”