What the Body Is

Choreographer Koosil-ja during a rehearsal of Wind Blowing On Us at DANY Studios in 2013. Photo by Frederick Bernas

Enter a koosil-ja/danceKUMIKO performance expecting to see ballet, tap, hip-hop—or any established genre of dance—and you will likely leave disappointed. Walk in expecting a multimedia event that stretches your conceptions of movement, dance, and the human body, and you may just experience something transcendent.

In fall of 2014, the innovative New York City dance company plans to debut a new project entitled Ecology of Image of Body, a creative collaboration between the company’s artistic director and choreographer Koosil-ja and composer and media artist Geoff Matters. Supported by an NEA Art Works grant, Ecology will continue the rich and gutsy experimental tradition established by its co-creators over the last decade, mixing the worlds of science and art to push boundaries for dancers and audiences alike.

Koosil-ja and Matters first crossed paths in the early 2000s as enthusiastic members of a cutting-edge and then-underground music scene in New York City. “I grew up in New York, studied at California Institute of Technology, and then returned in 2000 and began doing open media jam projects every week in the East Village,” described Matters, who also created GDAM, one of the world’s first DJ mixing and live music performance software programs. “People would come with all kinds of instruments—traditional and electronic, laptops, and other high-tech things—and we’d experiment and make music together.”

Koosil-ja, who had come to New York in 1981 to study dance with Merce Cunningham, gravitated toward the creative vibe of such events. “Though I have a dance background, I was always interested in electronic music, technology, and the energy of the scene,” she said. She met Matters at one of his GDAM workshops. “I was already the director of a dance company, and I invited him to compose music,” continued Koosil-ja. “He has a very special brain and has a unique way of working with the threads of my ideas.”

Though their backgrounds and areas of expertise differ greatly, both Koosil-ja and Matters clearly cherish the creative bond that they share. “I always find myself challenging her work and playing devil’s advocate,” said Matters. “About 60 percent of our collaboration is me going with what Koosil-ja wants, 20 is me pulling in the directions I want to go in, and another 20 is prodding her to help her figure out how she wants to pull the work itself.”

“It’s been great,” Koosil-ja added, laughing.Their first collaborative work came to life in 2003 in a grungy Brooklyn warehouse space. But more intriguing than the performance’s venue were the creative seeds that informed the piece. “I was trained in the Merce Cunningham technique, but I spent years trying to wash that style off of my body and to find my own vocabulary,” said Koosil-ja. “It occurred to me that, instead of solidifying a style in my own body, I shouldn’t have any style at all. I should copy everybody else’s way of movement. I also wanted to ask questions about being through questioning the body, what the body is and how it works, and to use images that could let us go deeper into those questions.”

|

As Koosil-ja and Matters began to further collaborate, such images often came in the form of video. “I use clips from movies, things uploaded to YouTube, anything that interests me from pop culture to hip-hop to a plastic bag floating in the air,” said Koosil-ja. “Whatever suits a particular project.” Some of the company’s rehearsals and performances have included dancers watching three videos simultaneously with each dancer’s head interpreting one source, arms and torso following a second, and legs receiving creative guidance from a third. And when it comes to the duo’s wedding of dance and technology, that’s just the beginning.

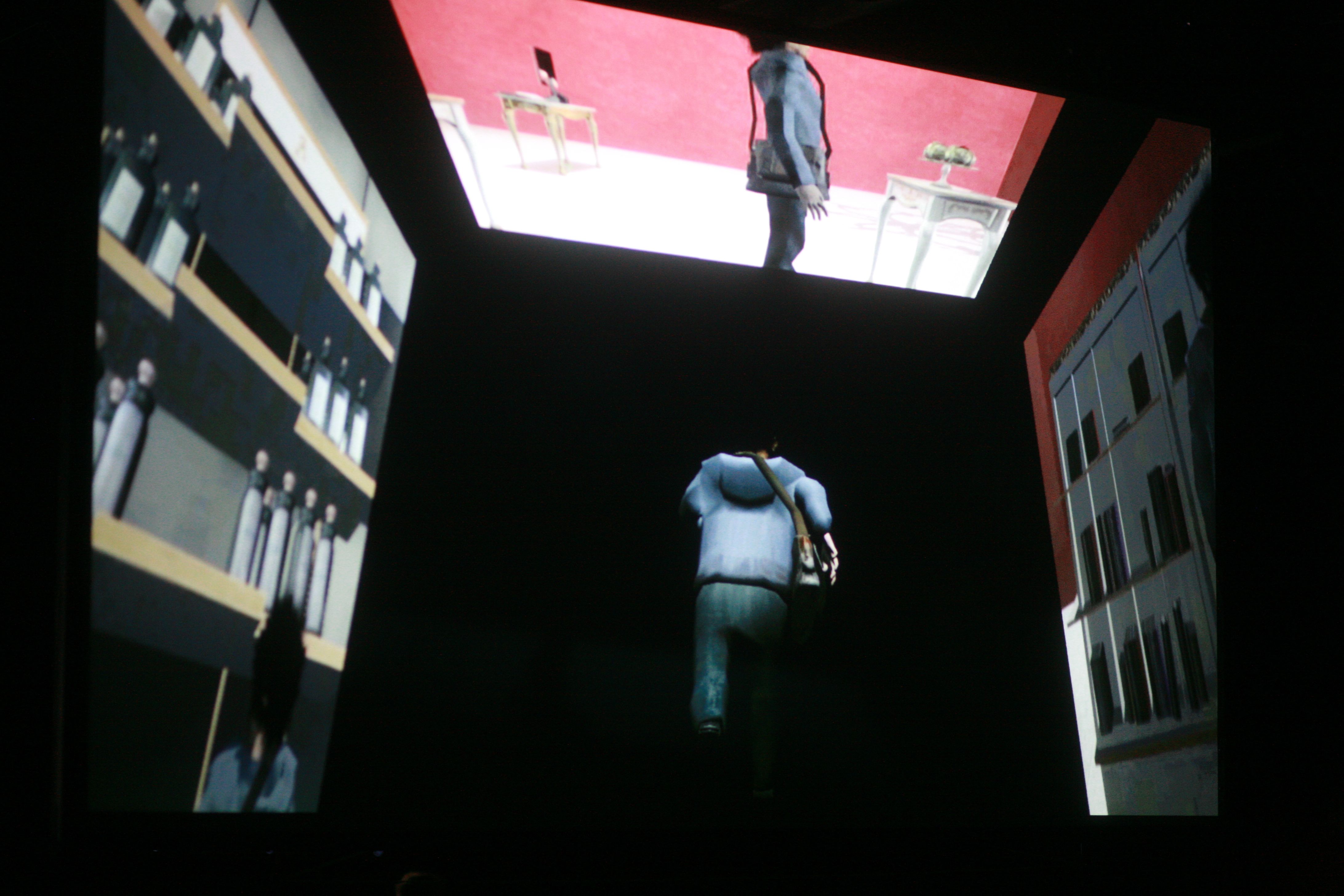

Koosil-ja/danceKUMIKO’s 2007 production, Dance Without Bodies, combined pre-recorded footage with live cameras, incorporating real-time visual feedback as an active element of the performance.

“The choreography was taken from dancers following video clips, as if their bodies and movement were being inhabited by this external force,” said Matters. “We split the performance area in half with cameras filming each half and projecting to the other side, so as dancers moved back and forth, you’d sometimes see them live, sometimes only see a projected image, and sometimes see a live dancer interacting with a projected image of another live dancer.”

Through the cameras and projections, the team sought to create an unexpected alchemy: remove the essence of the dance from the physical space, and the dancers’ willful independence from their own bodies, and place both in the realm of technology. “What happens to the domain of the body when the dancer can fluidly move between the real space and a projected image?” Matters asked. “That’s one of the questions we started to explore.”

Subsequent pieces have delved into similar themes. “What if we track the body’s movement and use it to manipulate objects in a 3D game space?” Matters continued. “What if we used dancers’ brain waves to generate music and manipulate physical, mechanical objects in the space?”

These are more than rhetorical questions. One technique that Koosil-ja and Matters have begun to explore in the creation of Ecology involves live dancers, brain wave-detecting headsets, and a carefully planned redirection of the audience’s focus from carbon- to silicon-based elements of the performance.

As Koosil-ja described it: “Imagine that the audience sees a dancer repeat the same phrase more than ten times—turn, spin, step—but each time, the dance movement becomes smaller and smaller as the dancer takes the movement into the internal place. Eventually they don’t see the physical dancer move at all.”

The dancer in question wears a brain wave-sensing headset that feeds information back into the performance via a system custom-designed by Matters. “As the movement of the dancer becomes invisibly small, the dancer’s brain is still actively dancing the dance,” he said. “The interplay between watching the dance disappear in physical form, but continuing to see it represented in the mental form, via video projections triggered by the brain wave readings, is another interesting aspect that we’re experimenting with.”

|

Even though koosil-ja/danceKUMIKO will be working with cutting-edge, brain wave-scanning headpieces, translating the information collected from those sensors into something creatively useful can be both a challenge and an opportunity. “Brain waves are based in this physical organ, but they’re electric impulses, fleeting and ethereal,” said Matters. “You can’t see them, but you can measure them. Data from the brain comes to us just as numbers, so we can use that information any way we want to.”

The field of neuroscience continues to progress in leaps and bounds, he said, but truly accessing the contents of a human brain, for creative purposes or otherwise, may amount to an impossible task. “There are billions of connections between synapses and capturing the amount of information being processed in the human brain at any given moment is beyond what any computer can handle and model,” said Matters. “The challenge is figuring out how to use some small portion of that information in a way that’s meaningful to us, and is most appropriate for the piece we’re working on.”

The ultimate goal of such experimentation for Ecology is to make the audience unlearn preconceptions, expectations, and associations concerning the body, Koosil-ja said—a process she described as “erasing attributions through this work.” Using his collaborator as an example, Matters explained further: “When you look at a dancer like Koosil-ja, you see a certain age, shape, size,” he said. “She has many attributes like number of limbs and features that are typical of humans. But through her dances and our collaborations, she wants to remove those kinds of attributions and move away from the human form to more abstract representations.”

“How far can we go erasing clichés of the body?” he asked. “Can we take something like a sphere, or a collection of spheres, and—through video technology, brain wave scans, motion detection, or some other type of technology—still have it be a representation or abstraction of the dancer? We want to take that idea and push it as far as it can go.”