Carolyn Mazloomi

Carolyn Mazloomi is as much a storyteller as she is a quilter. A 2014 NEA National Heritage Fellow, Mazloomi uses thread and needle to create a visual narrative of the African-American community and its history, from the Selma-to-Montgomery marches to Billie Holiday to church music and traditional ring shouts. Her work has been exhibited numerous places, from the Los Angeles Folk Art Museum and New Orleans Museum of Art to the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery—unusual accomplishments for a woman who received her doctorate in aerospace engineering. She founded the Women of Color Quilter’s Network (WCQN) (which today boats 1,700 members) in 1985, has authored five books on African-American quilts, and has curated a number of exhibits that have brought further attention to the art form. Considered the leading expert on African-American quilts, Mazloomi recently reflected on the community she has both fostered and reflected during her three decades of “living and breathing quilts.” From an interview with NEA Folk and Traditional Arts Director Barry Bergey, here she is in her own words.

Founding the Women of Color Quilter’s Network

Quilters are so giving, like most folk artists. They’re very special people. They’re very kindhearted people and very gentle people. I really feel that the creation of artwork is spirit-guided. We as artists are endowed with something from God that propels you to create the work that you do. It’s like a little miracle. Each piece, each quilt.

But I felt that there had to be an organization to safeguard the quilters and the quilts. As I traveled the country in my work, I was astounded by the cost that galleries were commanding for quilts. And that cost was not reflected in what the quilters were getting. So I felt that there should be an organization to disseminate information to the African-American quilters about not only the historic significance of the work, but the monetary value as well. Because they didn’t have a clue. It’s terrible for collectors and scholars to steal or misappropriate from the people that they are studying.

I hated to see too that the quilters gave away the work and did not leave anything within the culture, or leave anything to their families, to their children. You have to leave something behind, or we’ll wake up one day and be like folks in some parts of Africa—[much of ] the African antiquities are in Europe or European museums or American museums. All the best stuff is gone. We have to keep something for ourselves. That’s a mission for me: to find a place in American quilt history for the documentation of African-American quilts, because that’s been sorely lacking.

Respecting Variations

For decades, African Americans were not the scholars that were studying the quilts, and that caused a lot of misinformation about what African-American quilts are, what they’re about, how they look, the purpose of them. We didn’t have a say in that.

Because of early scholarship, people think in terms of the African-American quilts being improvisational, and that’s where that relationship to jazz comes in. But that’s not true, necessarily. That’s just one tiny little aspect of a quilting style that you can relate to African-American quilts. I wrote a book, Textural Rhythms: Quilting the Jazz Tradition, and in that book, there are narrative quilts as well as abstract quilts and improvisational quilts and all of those quilts related to jazz somehow. So that’s just one facet of what we do. I’m active in the quilt scholarship community to dispel the myth about what African-American quilts are all about. You cannot pigeonhole this work. It is not just about improvisation, even though early scholarship would have you think that. But that scholarship was not inclusive. The scholars were just looking at a certain set of quilts, utilitarian quilts, that came from the South, and declared that to be the definitive of what we made. We’re bigger than that. We’re broader than that. There are many styles of quilts made within the African-American community. The quilts are as varied as we are a people within the culture, so you can’t pigeonhole us.

Quilting the Story of a Community

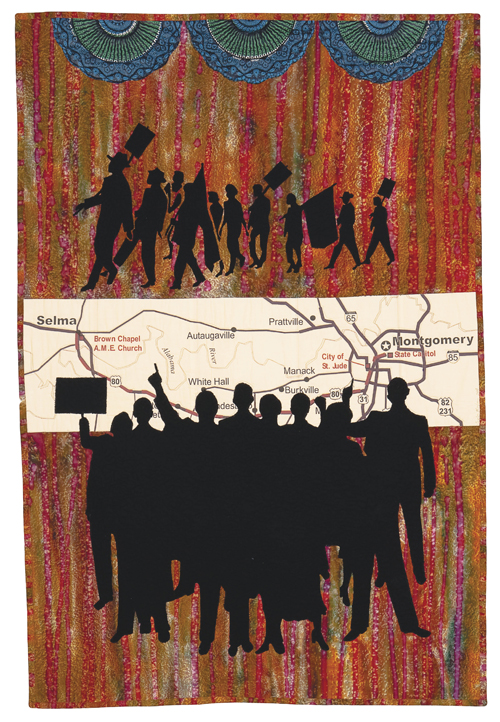

I love narrative quilts. Narrative quilts, or story quilts, that’s something we’ve been doing since we stepped off the boat. That is our community. When the quilters are in synch with the social and political and the cultural currents in their community, they render that in their artwork. So the quilts are community property. It’s one of the ways that we as artists use this tool, these quilts, to foster knowledge. And it’s about engaging other people in our culture as well.

I curate shows, and every show is like pulling teeth because the quilters don’t care if the public sees the quilts or not. The quilt wasn’t meant to be exhibited. They made them for the community. They made them for their families. They made them for their friends. [Exhibiting] is the last thing on their mind when they’re making a quilt. But they’re creating these community documents and actually they’re cultural documents. They’re pieces of history that tell the story of our culture, what’s happening here in the United States. They’re serious, serious cultural documents and I’m just in awe.

That’s the power of quilting, the ability of these African-American quilters to tell a story, to quilt a story. It’s amazing, with needle and thread, you can create such a powerful statement about the history of our country and who we are as a people. Every piece, to me, is a learning lesson. It’s a history lesson.

When you can look at something and it has the power to touch you and inform, then you’ve done your job as an artist. And I often tell the quilt makers sometimes you can make a quilt that’s so powerful in story and it touches so many people. Then you have lost that quilt, because the quilt does not spiritually belong to you anymore. It belongs to the public. It belongs to the people that see it because it becomes a part of their spirit, and it’s touched them in such a way that is so profound it becomes unforgettable. I see that so often in these African-American story quilts, how powerful they are. And how powerful they are in capacity to touch people’s lives.

It becomes a part of the story of our national community. It becomes a part of our whole collective history, the whole collective history of our country. These are powerful cultural documents. And that’s the allure, the mystique, the magic of quilts for me.

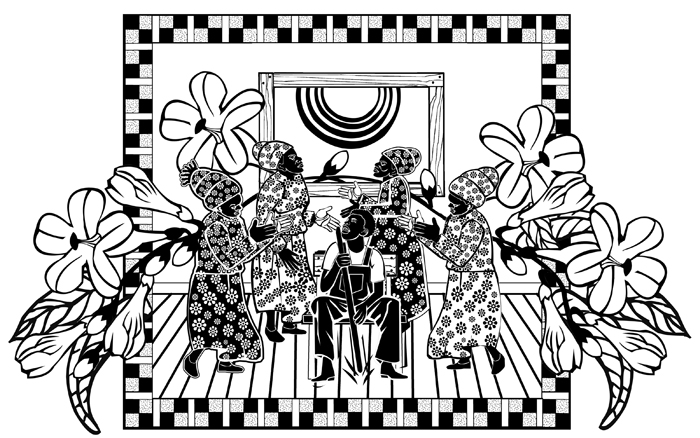

Carolyn Mazloomi’s quilt Ring Shout is based on a religious ritual practiced by the Gullah people of the Sea Islands, perhaps the oldest surviving African-American performance tradition in America. Image courtesy of artist

Fostering the Next Generation of Quilters

It’s been extremely difficult to teach young people quiltmaking. In this age of technology and hurry, hurry, they’re not interested in it. Some countries like Japan have so many special programs for young people to teach them their cultural arts. But it’s hard, in essence, for young people to lend themselves to making anything by hand.

We have several programs within the network to teach young people, and one of them has been ongoing for 20 years. But it’s a struggle to find the money to keep those programs going. I can count a couple of hundred kids across the nation, black kids, involved in programs where they’re being taught to quilt. It’s terrible because network members are dying every month. So it would be wonderful to cultivate new talent, and it’s out there. We have a program in Summerville, South Carolina, and the network member she’s just teaching a few kids, but I’m telling you it’s amazing. It’s amazing the ideas that come from these young people’s minds. So there’s a glimmer there. There’s a glimmer into what could possibly be the future if we could expand on that and give the kids the proper tools.