Back to the Fundamentals

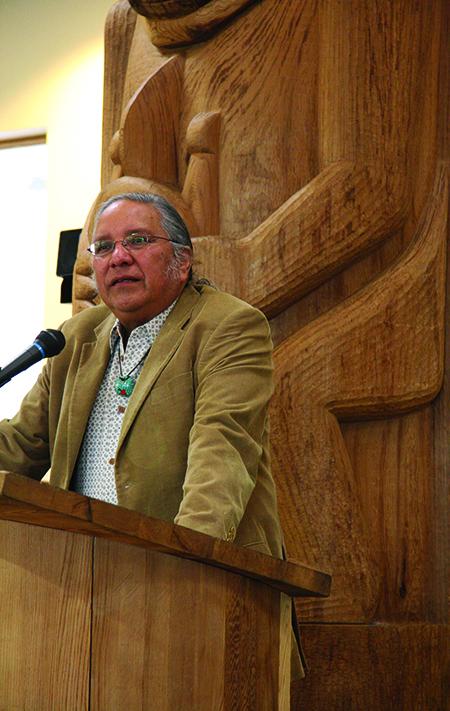

It is commonly said that the arts are so entwined with Native-American communities that many Native languages don’t even have a word for “art.” “From the day they’re born, [Native people] are essentially nurtured and invested in culture and its representation,” said Ted Jojola, a professor at the University of New Mexico’s School of Architecture and Planning. The problem is how to translate this ingrained cultural artistry into the built environment.

For Jojola, who also founded the Indigenous Design and Planning Institute and co-founded the Indigenous Planning Division of the American Planning Association, it is a matter of rethinking the traditional approach to community development. In his own words below, Jojola shares how the arts and creativity intersect with indigenous community planning.

PLANNING A RETURN TO HEALTHY COMMUNITIES

The one thing that I think is really important to understand about indigenous people is that we’re very much attuned to this concept of place and home. Many of our origin stories are invested in the idea that our people emerged in a very deliberate way, attuned to protocols and attuned to sacred places.

Indigenous planning is attuned to how the culture is represented. If you’re looking at indigenous communities, many of them were disrupted as a result of outside incursion, colonialism—whatever we want to call it. So it’s not that they never had the ability to plan communities in their own image; it’s that that disruption attuned them to processes and styles of development that aren’t necessarily healthy for them. Getting back to these fundamental principles they originally used is one of the things we’re trying to invigorate and instill in the communities that we work with. The basic goal is to bring back that notion of placemaking in a way that’s culturally meaningful and representative.

Healthy communities are places that are loved first and foremost. The way that we represent it is using something that we call a seven-generations model. Here’s where we deviate from what planners ordinarily do. As you know, when you get down to a strategic planning session, everybody talks about a five-year plan, a ten-year plan, a 20-year plan. Well, those are really artificial—maybe we do those because the math is simple. When you talk about it in terms of generation, it raises a whole different level of conversation. What can you imagine that your children are going to inherit, and their great-grandchildren? When you stage it in terms of that conversation, it takes on a whole different tone and brings out different types of perspectives and thinking. You understand that if we as individuals start something now, we may not actually end up living to see it completed. What is so compelling that our children and our future children will be compelled to continue it? When it is completed, [we want to make sure] it’s beautiful, it’s functional, it has meaning, and it’s loved by everybody.

|

TRANSLATING THE ARTS INTO THE LANDSCAPE

Art, as a Western construction, is based on this idea of originality and individualism. But what’s more central to the indigenous concept of art is expression attuned to representation of the collective. So images are refined and passed on through the generations. People are given the responsibility of being able to not just represent them, but also to carry on their meaning.

The community that we’re working with right now is Zuni Pueblo. A huge percentage of families are involved in some sort of arts production—it’s estimated that 80 percent of all households produce art in order to supplement their income. So the Zuni have this incredible reputation for producing arts such as jewelry, painting, so on and so forth. There are so many different types of art that are represented that respond to and respect the creativity of individuals to create these kinds of things.

So the question that really comes to bear is how do you then translate that into the contemporary landscape? This notion of art as a sense of representation—because of the disruption I talked about earlier—is no longer translating into the contemporary representation for modern buildings, modern streetscapes. We take for granted that these things are borrowed from other places. When you transplant them into a traditional community, do they really represent that community in a meaningful way? A huge challenge is trying to bridge that, and make a conscious attempt to negotiate these new kinds of buildings and new kinds of elements within a landscape.

This summer, we did a workshop on place-based learning [in the Zuni Pueblo community]. It was the first attempt to try and build a more critical way that people from the community discern their environment. If you grow up in a community, and that’s all you know, you just assume that things have always been the way they are. So this initiative raised awareness and meaningful discussions about: has it always been that way? Is it representative of the community? If not, how then could it be retuned to build a more meaningful representation?

As part of that process, we had over 60 people walk the area called Main Street. We broke them up into various groups, and the group walking with me noticed there was a new building—a bank. I asked them, “What do you think about this building that’s going up? Does it represent what you would like to see in Zuni?” Immediately they all chimed in and said, “Absolutely not. It looks like a shed. It looks like a warehouse.” They basically said, “We’re glad to see the bank is finally moving out of a trailer house, but it could have been so much more.” Right behind it was one of their sacred mesas. It was perfectly framed from the perspective and the view of this building. I think it was the first real awareness in the acknowledgment of how much better it could have been if they had been able to negotiate this. It could have been a beacon of culture, and something people could identify with and be proud of.

CREATIVE APPROACHES TO TEACHING CREATIVE PLACEMAKING

As [part of] this place-based learning workshop, we engaged high school youth, from 14 and up. Rather than bore them with the minutia and mechanics of what makes good design, what is land use, we wanted them to think out of the box as far as how they would imagine their environments and their landscapes.

We partnered with several other organizations including Creative Startups, ZETAC (a University of New Mexico teaching training group), and the Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers and Storytellers. It just so happens that the latter is in the throes of organizing the first-ever Indigenous Comic Con in November. The theme we gave the students was to develop their own Zuni superhero. What would a superhero be like that could actually use their superhuman powers to change the landscape? From that, we generated a lot of interesting conversations and built a really amazing set of new superhumans.

The long and short of it is now there are going to be 11 comic books that are going to be produced with these superhuman characters. Not only will they be showcased as part of this Indigenous Comic Con, but there’s also a gallery in Santa Fe [Form and Concept] that’s going to exhibit their original work. So I think that’s the latitude one can take in thinking beyond a staid mechanical perspective. I think challenging them, and using the foundation of their own perspective, culture, and values and then personifying them in this way really worked. But you don’t know until you try.