Opportunities for Creation

On September 14, 2016, Carla Hayden was sworn in as the 14th Librarian of Congress—the first African American and the first woman to hold the position. Given that many Librarians of Congress have been scholars or academics, it is also notable that Hayden is, in fact, a librarian. She began her career in Chicago, first as a librarian for the Museum of Science and Industry, and later as a children’s librarian in the Chicago Public Library (CPL), eventually becoming second-in-command for the entire CPL system. In 1993, she was appointed director of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore’s public library system. She garnered national attention during her tenure as president of the American Library Association (2003–2004) for her outspoken opposition to the Patriot Act, believing it violated library users’ privacy, and more recently, for keeping the Pratt Library open during the civil unrest that followed the death of Freddie Gray, an African-American man who died while in custody of the Baltimore Police.

Just a few days after coming to Washington, Hayden spoke with us about the role that creativity has played throughout her career, and the role she believes the Library of Congress plays within America’s creative community.

THE BENEFITS OF CREATIVITY

Creativity and inventiveness enhance community. Think of the fact that the Pratt Library, years ago, had a rap contest when rap was just coming out. The person who won was Tupac Shakur. There in a vault [in the Pratt]—next to an Audubon print and [a lock of] Edgar Allan Poe’s hair—is his handwritten library rap. He was 14 or 15 when he won. The librarian who drove him to the library that day put a “c” for copyright by his name, even at that time. So creativity and inspiring people to create and find ways to express all kinds of emotions I think can really help communities.

For instance, after the unrest [following the death of Freddie Gray], the library was a place that displayed photographs. Most of the cultural institutions in the city had displays of photographs from the unrest. We encouraged and had sponsorship to give kids cameras [to take photos of their communities].

One of my favorite prints that I’m going to put in this office is from the Children’s Museum of Chicago, years ago. There was a book that came out called Shooting Back: Photography by Homeless Children. The images are so striking. People express their feelings in a more positive and helpful way than, say, destroying property. People need a way to express their feelings. Libraries in communities can be places that can help people do that by encouraging creativity, but also by displaying their work and performing their work.

STARTING YOUNG

I did part of my doctoral work on museums serving children. I ended up saying that libraries needed to craft the environment of their children’s sections to reflect more of a children’s museum exhibit environment, and to have young people create, not just be receivers of content.

Over time, I’ve been able to put that into action, most recently at the Pratt Library—all of the children’s sections have those opportunities for creation, what we called creation stations. We incorporated music and movement in all of the programming as much as we could.

Then with early adolescents and teen programming, there’s make your own lanyards, make your own books, make your own music—even tie-dying has come back. And now there’s this whole maker space movement in libraries, and the ability to couple creating your own content with consuming content.

FORGING COMMUNITY AND CONNECTION

It was actually a very easy decision to open the library [during the unrest after Freddie Gray’s death]. I asked the staff if they would be willing to join me; I didn’t want to ask staff members to do anything that I wouldn’t do. Staff members at that particular branch were willing, and then we had staff members coming from other facilities that joined in to help out. It became quite the center in that community. It was the only thing that was open for media, for volunteers—people were coming from all over the country and even other countries to help volunteer to clean up the streets. It became a place where people connected, where they got water, where they had restrooms, food distribution, supplies.

[Keeping the library open] represented, especially in that community, what it had represented before that time: it was an opportunity center, it was a cultural center. What that particular action represented was that it was going to be there through thick or thin. Community members were so grateful that the institution that they depended on every day was there when they really needed it in so many other ways. That’s what it represented.

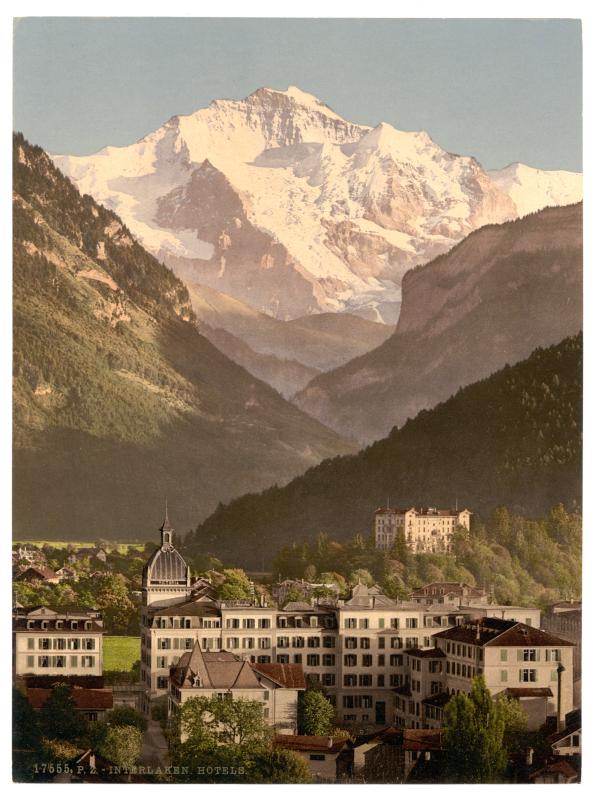

A photocrom print of hotels in Interlaken, Switzerland, circa 1890–1900. Wes Anderson used the Library of Congress’s online photocrom collection as inspiration for his film The Grand Budapest Hotel. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division |

NOW, AT THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

These experiences, and a number of others I’ve had in my career—as a librarian at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, working with curators and museum educators in opening up the first public access library in a museum in that city; teaching library science to new librarians—I think that combination of experiences is going to serve me well here.

The immediate vision on the horizon is to expand the accessibility of the collections and the services of the library, to make sure that the treasures are preserved and secure, and that the library really enhances the special services it provides to Congress and also to the creative community through the copyright laws. Hopefully at the end of my tenure there will be progress in those areas, and even more appreciation for what the library has and what it can do to help people in their lives. I want people to think, “Wow, I didn’t know the Library of Congress had the world’s largest collection of comic books.”

I’m just discovering the depth of the collection. I think the arts community would be very pleased by the treasures here. I’m looking at photography books now: One’s a book on lighthouses; there are others on canals, dance, furniture, documentary. It’s like being in a treasure chest. It’s a beautiful place, but it has beautiful things too. Not just beautiful, but things that make you think. The Library of Congress has inspired so many authors—all types of authors. But also documentary filmmakers—Ken Burns has extensively used the resources of the Library of Congress. Wes Anderson, one of my favorite filmmakers, credits the Library of Congress in researching imagery for The Grand Budapest Hotel. The Prints and Photographs Department is like heaven, I would think, for a visual artist. This particular library has so much to inspire and provide people who are involved with creating.